In 2001, Huey Johnson received the United Nations Environmental Programme’s prestigious Sasakawa Prize. When he got the letter, he read it, then tossed it on his desk with the other hundreds of papers requesting his attention. It took a full two days until someone in the office called the U.N. and confirmed that, yes, he was the year’s sole recipient of the $200,000 prize and would be honored at a ceremony in Washington, D.C.

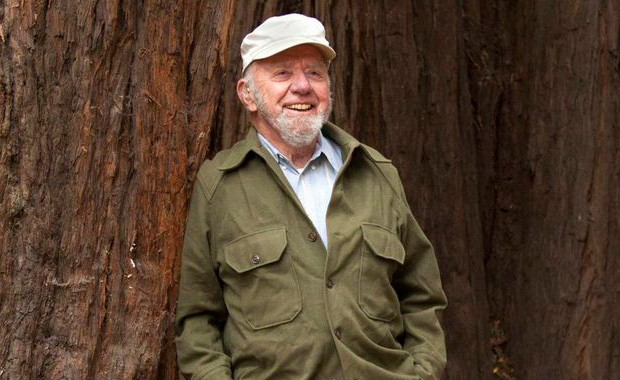

The octogenarian responsible for saving so much public land in Marin County and beyond is modest about his accomplishments. “Saving the lands at Golden Gate National Recreation Area, what good did that do for the world?” he says over lunch, a daily ritual for him and his small staff at the Resource Renewal Institute in Mill Valley. “Made me feel good—you get patted on the head all the time, they make a movie about you—but the world didn’t benefit very much from that.”

Those who know Johnson aren’t so dismissive about his achievements, which include starting the trailblazing Trust for Public Land.

“I think all of us working in conservation owe a lot to Huey,” says Ralph Benson, executive director of the Sonoma Land Trust. “He was one of the first people who really thought of conservation beginning in the inner city and extending into the wilderness. Trust for Public Land was all about land for people. He was a pioneer with that.”

Johnson heads up his own nonprofit devoted to saving the environment and fixing California’s fractured water system.

“I always try to look at big-scale problems,” he says. “In recent years, I’ve realized I’ve been very fortunate, probably very lucky, to be able to solve very small problems.”

In this case, however, “small” translates to hundreds of thousands of acres preserved as natural habitat, and planting seeds for thousands of environmental organizations to spring forth and create a national movement.

“He doesn’t put a lot of time into PR,” says San Rafael environmental journalist David Kupfer, who has known Johnson for about 30 years. “He’s not one to toot his own horn.”

‘This land is protected forever,” read signs erected on vast swaths of land purchased by land trusts. The North Bay has the Sonoma Land Trust, the Marin Area Land Trust and the Land Trust of Napa, but none would be possible without Johnson’s initiative. He founded the Trust for Public Land in 1972, which now has over 30 offices and 300 employees nationwide, with 5,300 park and conservation projects in 27 states. But more importantly, it served as a model for land trusts, and the roots of one-third of the nation’s 1,700 local land trusts can be traced directly back to the Trust for Public Land.

In Sonoma County, Johnson fought to save the 3,117-acre Pepperwood Preserve after the California Academy of Sciences, to which the land was donated upon the owner’s death, decided to reverse its original promise (and the deed’s stipulation) to preserve the land. In 1995, it went up for sale, and Johnson organized a publicity campaign against the decision. The academy bowed to public pressure and decided to preserve the land for research and field classes.

Johnson got into politics as Jerry Brown’s secretary for resources from 1978 to 1982. “I didn’t really want the job, but [Brown] really wanted me to do it,” he says. “I found that as an environmentalist I could get angry and hound at them to stop bulldozing a beautiful piece of land, or I could try and get policy established so that 10,000 bulldozers would be affected.”

Johnson has never run for higher office and has no plans to do so. “I accomplish more by being appointed,” he says, citing the promises politicians make, to both voters and special interests, that keep them from accomplishing as much as he’d like.

[page]

“I was able to do things I never even dreamed of doing,” Johnson says of his time in government. “I went ahead and got into a head-on, wide-open brawl with the timber industry and saved 1,200 miles of wild rivers. And on another occasion, I saved a couple of million of acres of land from being sold for logging. In each case, I just had to take on some special interests and slug it out.”

Johnson says he made adversaries, but stood his ground. “They weren’t happy when I was there. Several times, I was threatened. [Lobbyists] actually had the Legislature introduce a bill that would cancel my agency.” He laughs now because it didn’t pass. “In the end, the governor supported me.”

These days, he’s not so sure it would be possible to accomplish the same feat. “The system has been so corrupted by being able to buy elections that the special interests control the Legislature.”

After graduating from college in Michigan in 1956, Johnson went fishing to ponder his options in what was then a red-hot economy. “The river smelled badly, it was so polluted. There was oil on top of the water,” he says. “I sat there and I thought, ‘If these people in this state don’t care enough to look after the basis of life, then I don’t want to live here.'” So he took off for the wild blue yonder.

“When I got out of college, I worked for a company that manufactured cellulose tubing for hot dogs and hams,” he says, sitting behind the beautiful, huge one-tree slab of a desk a friend made for him in his office. “I was one of their hyper-experts. There were eight of us in the country. I was transferred all over all the time.”

This was 50 years ago when meat was king of the dinner, breakfast and lunch tables. Johnson was often assigned to work near the Sierra Nevada mountain range, and the avid sportsman liked his life. “In the trunk, I’d always have a ski box, rifle, shotgun and hiking gear, and I’d go find some dude ranch. I lived well.” But then came a long-term transfer to New York City.

“I was going to meet a friend, and I was holding a martini glass and I couldn’t hold it steady,” he says, shaking his hands for effect like Jell-O on horseback. “I was working 24/7 for weeks. I was so afraid I was going to fail, I was just killing myself. I was doing very well, but I thought, ‘Ah, this makes no sense.’ And then one of my bosses killed himself—committed suicide.” Johnson continues without pause, “And I quit and left and wandered around the world a couple years alone.”

He adds, “It was very important that I did that.”

From there, he got a job working for the Fish and Game Department in Lake Tahoe. He soon quit, but when Johnson does something, he makes a statement. One day, after being given “so many screwy instructions that were politically loaded,” he says, he resigned, hitchhiked to the Reno airport that morning and flew to Alaska. Once there, he says, “I had a job with the Fish and Game Department before nightfall.”

While in Alaska, Johnson discovered something important about himself. “I decided not to be a fishery biologist, because I was too close to the thing I love,” he says. “I didn’t want to lose the joy of life.” He was destined for a position higher in the food chain. “Without realizing it, I was more interested in public policy.”

Johnson got his master’s degree, then moved back to Michigan, where he grew up, to get a doctorate. “I saw a tacking on a bulletin board wall for a job in San Francisco, which is where I wanted to live, for the Nature Conservancy, which I had never heard of. So I walked into the phone booth, applied for the job, got it and never looked back,” says Johnson. “I was the eighth employee.” The Nature Conservancy now has a staff of over 3,800 in 30 countries, including all 50 U.S. states.

[page]

These days, Johnson is his own boss with the Resource Renewal Institute (RRI). This gives him the freedom to focus on projects of his choosing. “I didn’t want to punch anybody’s clock,” he says. “I wanted to enjoy being at work and wanted to enjoy the people I work with, and that became a priority and it worked out pretty well.”

One RRI project primed to make an impact soon is “Fish in the Fields.” As Johnson tells it, it was the calm between the quacks that sparked this idea to let fish and farms share the same water, to the benefit of both. “I was duck hunting, because I enjoy hunting. Duck hunting, you’re sitting in the middle of a flooded ocean, it seems like. Six hundred-thousand acres of California is flooded for rice, north of Sacramento to Chico. Ducks aren’t flying by that often, and you get to thinking.”

For the past six years, RRI has worked with biologists at UC Davis studying the potential of raising young salmon in the flooded rice plains. The naturally occurring plankton, it was discovered, fatten up the fish far better than traditional methods, and the efficient use of water could curb the squabbles over the use of Delta water. “The trouble with salmon,” says Johnson, “is they’re the holy grail of the fish world,” and many biologists’ careers depend on them.

But salmon aren’t the only fish that can thrive in this atmosphere, so Johnson had the idea to raise small freshwater fish to stem the collapse of the world’s feeder fish, like sardines, herring and anchovies.

Most of the fish consumed in the U.S. is imported, and most goes to pigs and chickens. The insatiable market for meat, combined with the growing aquaculture industry, is leading to situations around the world similar to 1950s Monterey, when the workforce of 25,000 found itself out of work one day when the sardine fishery disappeared, due in part to overfishing. Fisheries in South America, Canada and the Caribbean have been going dry in the past two years. “These effects are starting to descend, and we pay no attention,” says Johnson.

To that effect, the RRI recently built a hatchery for the Fish in the Fields project, making the project completely sustainable. Johnson says he hopes to make a business out of it—not to make money, but to set a precedent for others.

Tracing the problems of water supply back to its roots, Johnson started the Water Atlas to chronicle what he already knew was the case: California’s water-rights claim system is underfunded, unenforced and mismanaged. “The state agency that keeps the legal records hasn’t even got them all straightened out,” he says. “You just about had to hire an attorney, if you claimed you owned water; you’d go there and couldn’t figure out heads or tails.”

The Water Atlas (ca.statewater.org) shows an interactive map of water rights and rates throughout the state. It’s far from complete, but with the right funding, the project could become the state’s first comprehensive tracking system for water rights and prices through user input and Freedom of Information requests.

California’s water supply is being sucked dry at a rate four times its replenishment, Johnson says. Just about 71 million acre-feet of usable water from precipitation hits the ground in California each year; the state currently has claims for over 250 million acre-feet. “One of the first things we did was tally up the amount of legal claims that the courts go to when they want information,” says Johnson. “There it is, four times the amount of water that’s available.”

Say a vineyard wants to expand. They put in a claim to water at their proposed location with the State Water Resources Control Board, which is tasked with enforcement and regulation of water rights claims. “They’re supposed to be the enforcement group,” says Johnson. “You ask them if they’re enforcing anything and they say, ‘No, we don’t have the money.'” Water-rights claimers know this, and use it to their advantage. “What they do with the application is put it under a stack of about a thousand other applications. And they don’t have money to enforce it, so the stack grows and the streams die.”

At RRI, Johnson is not only the leader of the charge to save the environment but a perfect example of one of the nonprofit’s projects called Forces of Nature. It’s a series of interviews with conservationists who’ve made big impacts on the land; they’re like webisodes of the documentary Rebels with a Cause, which came out last year and features Johnson and others who helped create the Golden Gate National Recreation Area around Point Reyes.

Johnson’s perspective in the Forces of Nature interview is eye-opening: “The separation that is occurring through the advances in technology are so fascinating to people that they’ve abandoned the sense of awe that one gets from looking at a mountain at dawn, or duck hunting watching the dawn come, or being alone in a woods or a forest in a wilderness area. These are precious, precious assets that society owns. My worry is if we don’t create an ongoing awareness and connection, those will be lost. Water is the basis of life, connecting it to the oceans, connecting it to our own bodies, that it becomes a basic connection to life. And we doggone well better be aware of it and better do something to have it continue.”

In person, he defines the plight with just as much fervor. “I swim in a pond of problems as an environmentalist,” he says. “The most desperate problem we have threatening democracy in America is the need for campaign-finance reform. Because everything’s falling apart, and we don’t have a sense of why.”

But even through his pragmatic approach, Johnson keeps a positive attitude. “You can get bogged down with depression real easy,” he says, after describing one of those “how can politicians actually get away with this” situations that he’s working to correct. “So you’ve got to plug along and do what you can do, and if you persist long enough, you do some good.”