‘Change is kind of a tricky business.”

This pithy pronouncement, uttered in the opening scenes of Danai Gurira’s astonishing period drama The Convert, is both an understatement and a warning. Set in Colonial Africa in the late 1800s, the absorbing play follows a young African woman whose conversion to Catholicism puts her at the center of a violent cultural shift. As the occupying English empire imposes its rule, one of its tools of dominance is the church and its war on “pagan” practices.

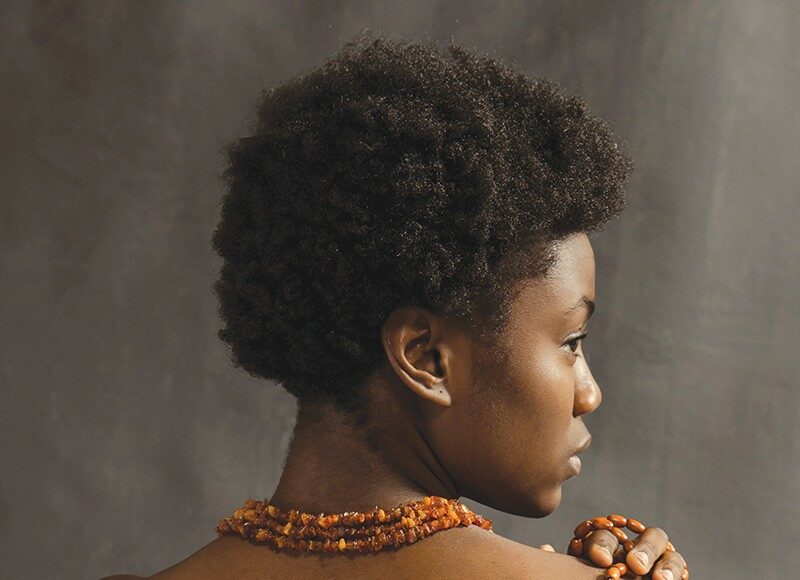

Young Jekesai (a transcendent performance by Katherine Renee Turner) has sought shelter at

the cement-floored home of

Mr. Chilford (Jabari Brisport), a pro-English Shona convert. The Shona are the largest ethnic group in Zimbabwe. Bare-breasted, terrified and speaking no English, the newcomer hopes to escape forced marriage to an elderly villager (L. Peter Callender, comically menacing perfection).

Chilford, along with his friend Chancellor (Jefferson A. Russell) and the latter’s educated fiancée, Prudence (Omoze Idehenre, amazing), have traded in their native names and dress for proper Victorian substitutes. As a result, they’ve incurred the suspicions of the locals, who call them traitors.

Jekesai has been brought to Chilford by her cousin, Tamba (JaBen Early), whose mother, Mai Tamba (a wonderful Elizabeth Carter), works there as a servant. It’s a job she keeps by feigning conversion to Christianity, erroneously reciting prayers (“Hail Mary, full of ghosts!”) while secretly maintaining her old customs. Mai Tamba encourages Jekesai—quickly dressed in “proper” attire and renamed Ester—to follow suit, not guessing the young woman will take to Christianity so quickly and passionately.

As local anger grows, Ester’s faith is put to increasingly impossible tests, her love of Jesus competing against her commitment to family, country and her most basic identity. Gorgeously written by Gurira and guided with exceptional skill by director Jasson Minadakis, The Convert only stumbles in its final moments, with a perplexing twist that seems less the inevitable result of previous actions, and more a calculated attempt at giving the play some shock value.

It’s a tiny issue in a play of monumental power and insight.

“You are lost!” Mai Tamba tells Ester. “Forgetting the ways of your people!” The play is a must-see. It illustrates, with impeccable beauty, how the changes we experience can affect more than just us. They also change our families, our communities and, sometimes, the world.

Rating (out of 5): ★★★★½