![[Metroactive Features]](/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | North Bay | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

College Issue

Dorm Spy

Examining the ethics of a prof who poses as a frosh

By Christopher Shea

It's not quite Tommy Lee Goes to College, the forthcoming NBC reality series in which the former Mötley Crüe drummer and varsity-level hedonist enrolls as a freshman at the University of Nebraska. But a fifty-something anthropologist who enrolled under a pseudonym as a freshman at the university where she teaches is making news of her own.

Some anthropologists are charging that a research project, which turned into a book titled My Freshman Year: What a Professor Learned by Becoming a Student (Cornell University Press; $24) by "Rebekah Nathan," was unethical. The question at hand: When does ethnography cross the line and become vaguely creepy spying on your students?

Few people have had the chance to read My Freshman Year, set at an unnamed large state university somewhere in the Southwest. But when the online magazine Inside Higher Ed previewed it in July, several academic readers objected vigorously to the book's premise. "Legal or not, the author has crossed some serious ethical lines," wrote "J. Langer," who claimed to be an assistant professor at the City University of New York, adding, "Shame on her."

One professor who helped review the book for Cornell, Margaret A. Eisenhart, a professor of educational anthropology and research methodology at the University of Colorado at Boulder, says she "loves" the book's content but found the whole project, at best, ethically ambiguous. There are "extraordinary circumstances" that might have justified Nathan's misleading research subjects, Eisenhart says, but finding out what students talk about when they are out of earshot of professors doesn't qualify. "I think she could have gotten the information without the disguise," she says.

The book's methodology is sure to draw more controversy than its content. The author--who describes herself in the book as a 5'2", 115-pound, 14-year veteran of her university (and who sounds on the phone far more like a freshman's mom than a bubbly co-ed)--states in the opening pages of My Freshman Year that she will give "short shrift" to such Tom Wolfe-ish subjects as "Greek life, dating, and sexuality"--thereby cutting potential readership by an estimated 98 percent. (A similar 1989 book, Coming of Age in New Jersey, for which the anthropologist Michael A. Moffatt went undercover at Rutgers University, included far more sex and drugs, to the point where one reviewer said some of the anecdotes in the book sounded as if they were lifted from Penthouse.)

Nathan's goal, she says in a phone interview, was to bridge the growing intellectual-culture chasm between her and her students, and answer such burning questions as "Why aren't students coming to my office hours? Why don't they do the readings for class?"

Nathan, who paid her own way and took no outside funding, lived in a single room in a freshman dorm, taking five courses her first semester and two in the second. (She says her grades ranged from A to C, the latter in an engineering class.) She played intramural volleyball and spent a couple of hours a day on her diary and other book-related activities (the equivalent, she says, of a student's part-time job).

Whatever budding intellectualism students feel, Nathan writes, is stamped out by pressure to fit in. In class, student queries rarely deviated from a "When is the next paper due?" script. Class discussions, at best, were "a sequential expression of opinion, spurred directly by a question or scenario devised by the teacher."

The exception to student tight-lippedness came in a wildly popular sexuality course, where students were encouraged to hold study sessions in hot tubs and to recount to each other their sexual histories in graphic detail. Nathan joined in and, since her discussion group had already taken a confidentiality pledge, outed herself as a professor in this small circle.

Still, Nathan's initial disdain for students who don't do their reading soon softened into empathy for 18-year-olds who must dash from class to class, cram and then work 10 to 20 hours a week--all while amassing the backpack full of activities that everyone tells them they need to land a job.

"What I learned, trying to do something similar, is that it's hard," says Nathan. She came to view cutting academic corners as a self-protective "utilitarian" strategy rather than evidence of laziness, especially since students are told from day one that they will learn more outside class than in it. (As a result of her research, Nathan says she has trimmed the reading list for her courses.)

"Community," a campus buzzword and universal goal of administrators, is dead on arrival in the dorm, where students hole up in their rooms with a handful of friends, entertainment centers and cell phones. And despite students' frequent claims that they have friends of different races, Nathan concludes that most white students have a diversity-free experience.

Some readers may lose patience with Nathan's nonjudgmental approach, especially when she attributes rampant cheating to students' busy schedules. But so far, criticism of the book has focused mostly on charges of spying and lying. In fact, Nathan admitted who she was to a small number of students, but she more typically responded to questions about her background by saying she sometimes worked as a writer. For extended interviews, she got formal consent, usually explaining only that they were part of a vague research project.

While critics say Nathan's research model sets a bad precedent, the truth is no one is likely to get hurt if the setting for her rather tame book is revealed. That's not the case for the pseudonymous sororities in Alexandra Robbins' recent journalistic exposé Pledged: The Secret Life of Sororities, whose tales of bingeing and purging, casual sex and genital piercings just landed it on the New York Times' paperback bestseller list.

And the sorority sisters are looking for the traitors in their midst who were Robbins's sources. "I've gotten e-mails from five or six sorority women, each at different sororities at different schools across the country, saying 'I am 99 percent certain you were at my school,'" says the Washington, D.C.�based Robbins. So far her secrets, like those of the fifty-something frosh, are safe.

[ North Bay | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © 2005 Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

Careers

Cheap Eats

Dorm Spy

Freshman 101

LEAP

Wish List

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

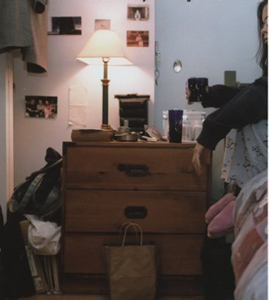

Ph.D. in Dorm's Clothing: This is the part where you buy the assertion that a 50-year-old professor passed for 18.

From the August 17-23, 2005 issue of the North Bay Bohemian.