![[MetroActive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Steamed!

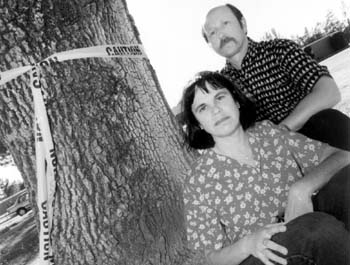

Making a stand: Geri and Tom Todd want to preserve native oaks in the path of a proposed pipeline route.

Santa Rosa plans to pipe 4 billion gallons of wastewater a year through everyone's backyard except its own. Think folks are mad?

By Janet Wells

SHIT HAPPENS, as everyone knows. What to do with it, however, is quite another matter. When it comes to Santa Rosa's 7 billion-gallon annual wastewater dilemma, city officials, developers, chamber boosters, and editorials ad nauseam in the local daily all cheerlead for the plan to pipe water 41 miles to the Geysers and turn it into steam electricity. Go with the flow, they say.

Full steam ahead!

But critics have their own take on the project, and boy, are they steamed. Dump practically potable water down a hole at a time when the same city officials are warning of drought conditions and hefty fines for water wasters?

What a waste!

Suffice it to say, Santa Rosa hasn't had an easy time getting rid of its wastewater. After more than $20 million, numerous studies, and 15 years of public outcry, lawsuits, failed proposals, ands scoldings from state and federal agencies, it's understandable that city officials are a mite sick of the issue. Just get rid of the darn stuff somehow.

"The [Santa Rosa] Board of Public Utilities has to make the decision," says Mark Green, executive director of Sonoma County Conservation Action, "and there are people on that board that I think personally are angry and frustrated that the environmental community has successfully thwarted three significant attempts at Santa Rosa solving this problem in an environmentally undesirable way."

Discharging wastewater into the ocean, building a west county dam, and dumping the treated water into the Russian River--all of those schemes, for one reason or another, got thumbs down from the public, the courts, or regulatory agencies.

So when the Geysers team stepped up to the plate, offering to accept wastewater that can be pumped into subterranean caverns and converted to steam-powered electricity, city officials jumped at the idea. In less than six months, the City Council endorsed a contract to deliver 11 million gallons of wastewater a day.

Not that everyone on the City Council is a Geysers groupie. Councilwoman Noreen Evans and former Councilwoman-turned-Assemblywoman Pat Wiggins voted against signing a contract with the Geysers, mostly because of cost-overrun concerns. And now Evans, along with council members Steve Rabinowitsh and Marsha Vas Dupre, is becoming an increasingly squeaky wheel lobbying for using whatever water is left over from the Geysers' share for agricultural and urban irrigation, even though much of it would likely go to wealthy vineyards.

BUT WHY NOT just use it all to maintain those green median strips, city parks, and fields? Money, apparently. It takes pipes, land, and massive storage reservoirs to get water from the treatment plant to the fields. The city's $88.5 million of the Geysers project will be passed on to the ratepayers, resulting in a $5-$6 increase each month. An all-reuse program would be considerably more expensive, and would increase rates even more, city officials say.

"The Geysers option was available, it made sense in a way, and it solved the Russian River problem," says Bill Mailliard, chairman of the infrastructure committee for Sonoma County Alliance, noting that the city soon can stop dumping its problem into the river. "I think reuse is a concept that's fine, but when you actually try to get people to come forward and put this much money into it, nobody stands up. Reuse has mostly been a theoretical question. As far as I know, whenever people have been asked, 'OK, what are you willing to do to have this water?' somehow it all gets very vague."

But the public has indicated a liking for agricultural and urban reuse, even if it is more expensive. So the city is at last making an effort at compromise.

Last week, Evans returned beaming from a meeting at city hall. "We've gone a long way towards agricultural reuse in the last couple of weeks," she says. "We're really going to do it."

Santa Rosa does have a wastewater reuse program that irrigates about 6,000 acres of farmland and urban landscaping. The program is considered a model in the state, but it hardly is economically viable, since the city actually has to pay some of the growers to take the water. If farmers want a share of the wastewater, they are going to have to pony up some serious cash to get it. They are, it seems, ready.

For the past several months a group of central county farmers has quietly pursued bank financing and plans for the Vast Oaks Project, a huge storage reservoir just east of Rohnert Park with a capacity to hold 360 million gallons of treated wastewater for use in the summer when water is at its scarcest. Ed Grossi, a Penngrove fruit and vegetable farmer, says there are four to eight landowners interested, and the city has earmarked $6.9 million to help build the project.

On a larger scale, owing mostly to public pressure, the council earmarked $30 million to deliver wastewater to farmers in the Alexander Valley along the Geysers pipeline route. But two thirds of that was siphoned off last week to pay for a bigger pipeline, leaving a mere $10 million to develop agricultural reuse programs--and Santa Rosa consultants estimate $56 million would be needed to create a viable ag program.

"We're willing to live with the Geysers if Santa Rosa is willing to have a real agricultural irrigation project," Green says. "The Alexander Valley irrigation that they're talking about doing does not qualify. The only thing that water is going to do is benefit Kendall-Jackson for building more hillside vineyards in the Alexander Valley, and that's not a public benefit. I can't see the citizens of Santa Rosa wanting to subsidize hillside vineyard development with their wastewater."

There's time to put in your two cents before city officials finalize the route.

A look at Santa Rosa's wastewater history.

REUSE isn't the only politically correct selling point of the Geysers plan. Santa Rosa officials tout the opportunity for cities along the pipeline to tie in to the pipeline and solve their own wastewater issues.

The offer, however, hasn't exactly spurred a jump-on-the-bandwagon response.

"I have concerns about hooking into a system into which we have no voice and no control," says Windsor Mayor Lynn Morehouse. "We have no control over what this [Santa Rosa wastewater pipeline project] is going to cost."

Windsor did send a letter indicating interest in the option, but it will take at least a year to analyze the environmental impacts and make a decision, Morehouse says.

While Healdsburg Mayor Mark Gleason likes having the option to tap into the Geysers pipeline in the future, for now the city is pursuing an upgrade of its own system to sell tertiary treated wastewater to agriculture. "Then we're self-sufficient," he says. "We're going to do our own thing."

In addition to critics harping about reuse and costs, there seems to be an unlimited supply of Geysers naysayers who simply view the project as an unwelcome invasion.

The Alexander Valley Association, unhappy that the pipeline snakes through its steep vineyard-studded hills, filed a suit against the city that is still pending.

The Madrone Audubon Society also filed a suit against the city, for proposing to put the pipeline through the society-owned and environmentally sensitive Macayamas Mountain Sanctuary, a bird, plant, and wildlife refuge north of Healdsburg. The group, practically powerless against the city's eminent-domain authority, settled the suit in September, winning $260,000 and a promise of more money if the city decides to run the pipe several miles through the sanctuary along a PG&E right-of-way corridor.

City officials are anxious for the Audubon Society to endorse by July 1 one of two northern pipeline routes: the PG&E right-of-way, known as the modified Pine Flat route, or the Burns Creek route, which cuts through about 1,000 feet of the sanctuary's top end. But the group refuses to make a decision before plant studies of the sanctuary are complete in several months.

"We want to make sure we don't rush into things just because the city has a time line," says Joan Dranginis, president of the Madrone Audubon Society. "They are rushing us a little bit, because they know they have right-of-way issues with private-land owners, which are a sticky wicket for them."

Indeed. Residents of unincorporated county land along the southern portion of the pipeline route are up in arms. When residents of the Piezzi and Willowside road area learned that the pipeline would knock out more than a hundred oak trees in their neighborhood, they mobilized a grassroots protest, tying yellow construction tape around the doomed trees and staking "Save Avenue of the Oaks" signs in their front yards.

But most of the trees are in the public right-of-way, which gives the residents little leverage. "I feel those oak trees are as much mine as if they were in my own yard. They belong to all of us," says Geri Todd, who lives less than a block from the pipeline route.

The ribbons and the signs stayed up less than a week before someone snuck into the neighborhood one recent Sunday evening and quietly took everything down. "Apparently we struck a nerve with somebody," says Geri's husband, Tom. "We're upset. We're using our power of freedom of speech and expression, and there's somebody who's trying to circumvent that."

Councilwoman Evans winces when she hears stories like the Todds'. "I'm very worried about it. I live on a street covered with oak trees. I would not be happy if a jurisdiction came in and told me they would be taken out," she says.

Evans concedes that the Geysers project is bound to leave someone--and potentially a lot of people--unhappy. "The question is how can we do the least damage and have the least impact," she says.

[ Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Michael Amsler![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

From the June 24-30, 1999 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.