![[MetroActive Features]](/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

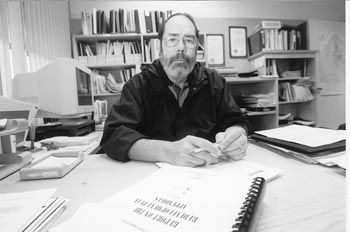

The man with the plan: West county Supervisor Mike Reilly supports the recommendations of a $100,000 study urging redevelopment of impoverished Russian River communities, but constituents are unsure about the ultimate cost.

River Watch

Russian River-area residents look the redevelopment gift horse in the mouth

By Stephanie Hiller

TO HEAR IT from Sonoma County Supervisor Mike Reilly, the redevelopment sounds like the best thing to come down the river since the steelhead left: Monte Rio and Guerneville, forested river towns suffering from depressed economies, sharing in an estimated $185 million in new tax money over the next 45 years and transformed into lively little hubs, with nice structures tastefully redesigned and a flourishing tourist industry.

According to Reilly, redevelopment means money for housing renovation, river restoration, a new park by the historic old bridge, a community center, a park and trail in Monte Rio--"amenities that both visitors and residents could enjoy."

But the community isn't buying it, or at least 90 percent of the community isn't, by activist Brenda Adelman's reckoning. "We care about different things, and they're not things you can put a price tag on," she says. "We don't want to look like the rest of the county. And we don't necessarily want more tourists here."

At the first meeting of the Russian River Forum, held May 3 in the supervisors' chambers to give the public a chance to comment on the redevelopment plan, which was released last November, Guerneville resident Steven Spector, who followed the plan closely, painted a grim picture of tall hotels and parking lots from Rio Nido to the Rio Theater, sort of a biggest little city in the west county--Reno without the gambling halls.

Activist Lenny Weinstein calls this plan "affirmative action for developers."

Although he believes Reilly is "sincere," Weinstein suspects political ambitions are the ulterior motive. Others have accused Reilly of being in the pocket of the developers, a remark that makes the embroiled supervisor laugh.

"When all this is over," he remarks, "we'll see who is in whose pocket."

REILLY HAS MADE his name in these parts by doing good for people who need help. The head of West County Community Services for 10 years and a committed environmentalist, he is especially proud of the establishment of the Guerneville Senior Center, which he got built with what he calls "guilt money" from developers.

In his first campaign for the supervisor's post, four years ago, Reilly stressed his commitment to urban growth boundaries. "I've always been a limited-growth person, and I've said that we don't need to be taking major residential growth into the west county." Then what's all the fuss about redevelopment?

"Fear of change," he calls it.

We are sitting at a table on the outdoor patio at Reilly's favorite hangout, the Northwood Restaurant, located on the golf course outside Guerneville. With its rich green lawns and golfers, it's the closest thing to a country club the west county has to offer. Alluding to the hectic day he has just spent driving up and down the freeway to cover his beat, Reilly orders a pint of fawn-colored ale.

"Redevelopment will result in little if any residential growth," he says. "The only new residential development even anticipated in the 30 years of the plan is for affordable housing. Everything else is focused on rehab of existing units.

"If there's residential growth, it's not because of redevelopment."

Business development will occur only within the current "commercial footprint." And the plan "will have to live within the bounds of the present infrastructure."

As for the towering hotels, "there's only one that I know of right now"--that is Kirk Lok's proposed 150-room edifice, twice the size of his new Sebastopol hotel. One hotel not only can add to the tax base, but also becomes an "umbrella" to support smaller bed and breakfasts. The goal is to bring back the 300 or so rooms that the river area has lost over the past 20 years with the demise of Southside, River Village, Donovan's, Hexagon House, and the like.

"I don't think bringing that many [rooms] back will break the back of the river community," Reilly says.

Maybe not, but many locals continue to feel they are being steamrollered into something that will change the face of their community.

Jim Neeley, spokesperson for Guerneville's fire district, runs a tax and securities business in Santa Rosa. Only 20 percent of property tax increases from redevelopment will go to the fire district, he says. Instead, "developers can get cheap money. Probably tax relief, too."

THE DREADED proposed regional sewer plant will have to be built, Neeley believes, to supply needed infrastructure. Like other opponents, he challenges the definition of blight on which the plan is based. "How did Northwood get to be a blighted area? There are half-million-dollar homes there!"

And why won't the county reveal the addresses of these so-called blighted homes, asks Roni Bourque, 62, who has found "thousands of pages" on redevelopment abuse around the country on the Internet, and "something like a million lawsuits against it."

She's worried that her property taxes will be higher than she can afford and she'll have to move. And "the practice of eminent domain is horrific," she says, though Reilly has said that the county is not retaining that right over residential properties.

But Bourque is not persuaded by Reilly's assurances. "This [plan] is money-driven, it has to be."

Attorney Barbara Barrett, president of the Guerneville Chamber of Commerce, acknowledges that there have been problems with redevelopment, mostly prior to 1993. Since then, she says, laws have gotten stricter. She challenges the assertion that 90 percent of local residents are opposed to the plan. Supporters agree that redevelopment anxiety might be allayed if citizens had greater input in its implementation.

To that end, Reilly promises to recommend the formation of a citizens' advisory committee that will review all building proposals. The county Board of Supervisors will have the final say, but only on projects that the committee recommends.

"At least the committee will have the ability to say no, which is an important control mechanism," he chuckles, "maybe the most important control mechanism."

[ Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Photograph by Michael Amsler

From the May 18-24, 2000 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.