![[MetroActive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Sonoma County Independent | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Uphill Battle

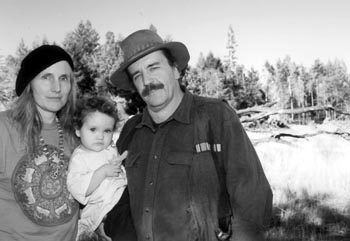

Eye on the prize: Cazadero resident Tom Kelley, with his wife, Susan, and daughter Anna Marie, says that the pristine wilderness that drew him to the west county is being destroyed by irresponsible vineyard practices.

Local vineyard boom raises hackles in backwoods areas

By Dylan Bennett

THE FERTILE HILLS of western Sonoma County yield a prime climate for the prosperous vineyard industry. Yet the growth of grapes has jarred the environmental sensibilities of many country folks and recently has aroused legal and social conflict in two pristine rural neighborhoods. The incidents are just the latest in a string of similar encounters that have led to the demand for a county steep-slope ordinance to regulate the conversion of woodlands to vineyards.

Most recently, Sonoma County Deputy District Attorney Jeffrey Holtzman has filed criminal misdemeanor charges against the Peter Michael Winery and logging operator Ken Parmeter allegedly for clear-cutting 30 acres of forestland at 1,200 feet of elevation in Cazadero in late October without the required timberland conversion permit.

"It's really shocking," says neighbor Tom Kelly, noting that the devastation has harmed the views and caused increased erosion. "Picture in your mind the prettiest hills you've ever seen. Now picture a large swath bulldozed off. The topsoil is now in the south fork of the Gualala River."

Any penalty handed down from the court in the case will likely pale in comparison to the lingering ill will generated in the rural community. "There are still major erosion issues and conversion issues," says Cazadero resident Annie Creswell. "Where are they going to get the water? They buried a huge pile of logs in the canyon in seasonal streams above the river. That's a breeding ground for salmon. There's going to be an effect on the river regardless of what they do."

Bill Vyenielo, general manager of the Peter Michael Winery, says that his company didn't know it was required to get a permit and that the logging operator now openly says he gave false information regarding permits. "We are working with all resource agencies following the letter of the law. We are reasonable, experienced people and want to work with our neighbors."

On Bones Lane, a narrow, tree-lined dirt road near Graton, concerns about water supply, pesticides, and corporate behavior have residents along the lane anxious about Kendall-Jackson Winery's plan to expand its vineyards--part of nearly 8,000 acres the company has under cultivation in the state. The huge Santa Rosa-based international wine company plans to cultivate a new 127-acre vineyard for pinot noir and chardonnay grapes on a 189-acre parcel there. Forty-three acres of the spread have been cleared of an old apple orchard, and plans call for cutting 84 acres of timber.

Large amounts of winter runoff collected in ponds will irrigate the Bones Lane grapes in summer, but locals say the watershed features unique, water-scarce, "serpentine" geology, and such water collection plus the removal of trees could reduce the well-water supply for neighboring houses.

The best effort thus far to curb the harmful effects of erosion into the beleaguered Russian River and threatened salmon- and steelhead-supporting streams is the proposed hillside vineyard ordinance conceived by the Watershed Protection Alliance, a committee of environmentalists and grape growers, and submitted to the county supervisors for approval.

The basic provisions of the proposed ordinance prohibit vineyards on slopes over 50 percent, and stipulate a tiered system of stream setbacks that starts at 15 percent.

Whether the ordinance is a positive step or an empty political gesture is a bone of contention among environmentalists. Negotiations began a year ago under the leadership of Sonoma County Conservation Action, but as the provisions were finalized in September, committee members Farm Bureau president Richard Mounts and environmental attorney Kimberly Burr of Forestville both refused to sign them. Mounts says the Farm Bureau's local board couldn't accept a 50-foot riparian no-touch zone.

Burr charges the provisions will fail to protect wildlife habitat. He points to criteria from the National Marine Fisheries Service that call for 300-foot-wide no-touch zones around streams.

"The main reason we were there was to protect habitat, and that got taken off the table," Burr laments. "The growers will play this ordinance like a violin. It's just fake, a big facade."

Rick Theis, executive director of the Sonoma County Grape Growers Association, a non-elected post he's leaving at the end of January, disagrees. "It's a tremendous environmental victory in terms of soil conservation and protection of streams and fisheries," he asserts. "If you need to put wildlife habitat on the scoreboard, that game is not over.

"For those who wanted wildlife habitat to be a part, I'm certain they're disappointed."

ATTORNEY BURR says the proposed county ordinance, which is expected to regulate vineyard development on steep slopes by next growing season, has lent a sense of urgency to the region's $300 million wine-grape industry to develop as much as possible before regulations take effect. In Cazadero, some residents of this heavily forested rural community say they have received letters from a winery offering to buy their property in lots as small as 10 acres.

The new county law that will prohibit vineyards on slopes over 50 percent--45 degrees equals 100 percent--also stipulates the width of no-touch zones along environmentally sensitive streams and rivers. Even if the ordinance were in force already, it would not affect the Kendall-Jackson project, so the new rules won't provide an easy answer to the ongoing collision of residential and agricultural rights.

Part of the Graton fight centers on Kendall-Jackson's ownership of a 1,500-foot strip that contains Bones Lane, which residents want kept at its current width. If strictly enforced, K-J's ownership of the lane entitles the company to several yards of each neighbor's property along the lane. "Our position is we own it because we bought it," says K-J's director of real estate, Tony Korman, who adds that his company has no plans to widen Bones Lane.

But residents like Edgar Castellini, a Santa Rosa Junior College English literature professor, don't trust the large wine company not to extensively expand its operation beyond a vineyard to include a processing facility, a wider road, and increased traffic. In an ongoing lawsuit from 1994, Castellini and four other neighbors have asserted that any right-of-way on Bones Lane is limited to the existing lane.

Last year, Castellini says, the neighbors hired a hydrologist who found that the proposed K-J vineyard conversion would lower the water table in the area. Now the Bones Lane project awaits the result of an anxiously awaited environmental impact report expected to be released shortly.

The picturesque vista at the end of Bones Lane overlooks the K-J property. In the distance, the rolling symmetry of the vineyards blankets the valley floor and appears to creep into the hills. Relevant to the conflict in the west county is the environmental awareness of residents who won't accept pesticides or further damage to the Russian River and fear the relentless push for more vineyards while the county lacks a plan to balance the vineyard growth with other considerations. "We are becoming a one-crop area," says Bones Lane resident Ann Maurice, a local wastewater-policy watchdog. "Monoculture is bad news."

Vineyards are indeed increasing at a dramatic rate in Sonoma County. Deputy County Agricultural Commissioner Pierre Gadd says that, because of the rapid growth, the county "doesn't have a handle on all the acres" under vineyard cultivation beyond the rough count of 40,000 acres. That figure, up from 31,000 acres in 1987, could easily be higher. Gadd says his office will attempt a solid count this winter.

But there's no question that Kendall-Jackson is at the forefront of this viticultural expansion. On Dec. 10, the company won county approval for its $18 million, 164,000-square-foot Stonestreet wine production facility in Alexander Valley, over the expressed opposition of neighbors and some small grape growers who don't want the industry to change the area's quiet rural setting.

Kendall-Jackson, which hopes to increase yield and cultivate another 1,000 acres in Sonoma County in the next two years, is pushing ahead with its expansion plans, despite opposition. "Anywhere there's good land, we'll be looking at it," says K-J spokesman Mike Winters.

That's disheartening for local conservationists who feel the company is changing the landscape to the detriment of the community. "I would love Kendall-Jackson to take an innovative stance," muses Maurice, who adds that if she could "wave a magic wand" the wine company would plant deep-root vines that don't require irrigation, cultivate organically, and plant only in existing open space without cutting trees or scraping hillsides. "Be like the west county, for God's sake," she says. "Get in step with the neighborhood."

Such a magic wand, Korman says, isn't realistic.

In Cazadero, neighbor Tom Kelly echoes Maurice's position: "Think of win-win solutions," he suggests. "Leave out the mega-spraying and the methyl bromide, and put in a world-class organic vineyard, and I think 90 percent of the community opposition would vanish."

Paul Jaffe, owner of Copperfield's Books, lives immediately downhill from K-J's Bones Lane property: "It's really a bigger environmental issue around a watershed that affects Atascadero Creek, into the bigger watershed of the Russian River, and they are all connected," he says. "I'm sorry to see everything done on a piecemeal basis and nothing done on cumulative impacts."

[ Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Michael Amsler

From the December 31, 1998-January 6, 1999 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.