Culture Vultures

Photo by Christopher Gardner

Designers are jonesing for street wear

By Laura Compton

MY FRIEND JEFF used to be the most devoted thrifter I knew. An accountant by day and artist the rest of the time, he visited Salvation Army sometimes twice a day, hit garage sales and flea markets every weekend, and created wallets and art out of construction signs and other unlikely elements. Recently, however, his personal style has evolved from vintage gabardine shirts, white T-shirts, and paint-splattered khakis to baggy designer jeans and flamboyant Nikes.

In short, he's gone from a thrift scorer to a fashion junkie.

Fashion junkies used to be slaves to European couture dreams--the fancies of designers inspired by art, history, certain French actresses, and perhaps a period epic such as Amadeus. The media still propagate this version, with their coverage of the seasonal runway shows, designer and supermodel cults of personality, and the endless litany of what's in, what's out, and what's back.

But these days, the true fashion Zeitgeist is firmly entrenched in the States. The unique styles of some of America's most disenfranchised, marginalized groups are being systematically raided and appropriated. Add in the forces of pop culture, music, and good, old-fashioned capitalism, and the result is a syncretic "low" fashion that increasingly blurs the lines of its origins. Smart designers tweak and steal street fashions, then send them back out as hip new products, all while charging outrageously high prices.

Look no further than the Macy's display windows, Foot Locker, or the Pavilions' boutiques, and you'll see items that look eerily familiar--but are suddenly way out of your price range.

"It's now about chase and flight: Designers and retailers and the mass consumer [are] giving chase to the elusive prey of street cool," Malcolm Gladwell wrote in the New Yorker magazine earlier this year. The article, which introduced the term "coolhunt" into the popular lexicon, explained how athletic-shoe companies such as Reebok and Converse run prototypes of new products by urban youth in "happening" cities such as New York, Detroit, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Philadelphia.

The reasoning goes like this: Cool kids want the real shit and often create their own trends. They know what's hot instinctively, know what they and their friends will buy, and don't take kindly to lame imitations. Models, rap and hip-hop musicians, and sports figures might popularize the styles to the masses via MTV and style magazines such as Details and Grand Royal, but it's a symbiotic relationship that originates in the street.

Designers often revamp or scrap styles based on initial street reaction. Older trends, such as the Converse One-Star basketball shoes and Hush Puppies, are now back in force because they were selling so well in thrift and secondhand stores.

How big is this market? Unbelievably, basketball shoes alone are a $7.5 billion market worldwide. "It's ironic that the same demographic group demonized by right-wing politicians, harassed by the police, and ignored by employers is the most sought-after by many of America's richest entertainment and apparel companies, who seek the blessings of their authenticity, then sell it back to them for an inflated price," comments an article in a recent Spin magazine.

But it goes beyond irony. The same baggy clothes and athletic wear that can land ethnic teens on "gang wannabe" lists are now marketed to suburban teenagers who want the tough image without the reality. Hip-hop style has permeated youth fashion and become so commercialized in recent years that much of it has been rendered innocuous, but it's a process of constant evolution. As creative modes of dressing continue to come up through the streets, they will inevitably continue to be redone with designer names and exorbitant prices.

Hip-hop culture is just one example. Culture vultures know no boundaries; other groups whose distinct elements have become fashion fodder include skateboarders and snowboarders (baggy pants, Vans); Latinos (baggy shorts, tank tops); punks (studded belts and jewelry, Converse, men's pants); and riot grrrls (Mary Janes, barrettes). The act of appropriation not only divests these symbols of power, but also blurs their origins until they are no longer distinguishable.

One term you'll never see mentioned in fashion ads or media is class. Instead, its surrogate code words are campy, kitschy, hip, retro. Trailer parks, alleys, and bedraggled urban areas are the backdrops for both ads and editorial spreads. Take the short-lived, much-ballyhooed "heroin chic" fashion stance that President Clinton and others were so up in arms about. Ads and fashion layouts from such designers as Diesel and Calvin Klein, with their malnourished, drugged-looking models in hooker get-ups, were glamorizing poverty, not heroin. In today's political climate, with its rapidly unraveling welfare system and safety net, low-income women are simultaneously blamed for society's ills and held up as fashion plates.

Magazines such as Spin and Rolling Stone, with their double-page color ads and au courant fashion spreads, function as a guidebook of co-optation as designers desperately try to sell cool and rebellion.

Often the co-optation goes beyond the styles to the sources. Declassé styles of yesterday that we once held up as examples of bad taste or age--polyester, leisure suits, loud prints--have now been recycled and revived for a several-decades-removed generation. Thrift stores, a perennial font of older styles, have been pillaged. It's bad enough that retailers are remaking old styles and charging an arm and a leg for them, but it's truly galling to find Thrift Town picked over, and polyester shirts selling for $20 (versus $2 or $3) at Urban Outfitters.

A September fashion spread in Spin advises readers on how to trade in '70s designer fashions for '80s variations. "Feeling imprisoned by that suit and tie?" it asks. "Longing for the grunged-out Courtney?"

Ironically, in recalling the time when Courtney Love's clothing choices expressed personal sentiments more than designer ones, Spin seemingly contradicts Harper's Bazaar, which recently put Love on the cover because her "severe good looks and sensational background (the drugs, the booze, the rawness) suddenly conform with fashion's hard-edged glamour." However you choose to frame it, it's still about selling a look, whether it's kinder-whore or Klein.

Isn't a fashion-blind society, where our differences are obscured and thus become unimportant, a worthy goal? Maybe in theory. But fashion is a form of personal expression. In our visually oriented age, it sends an immediate first impression. Throughout history, disenfranchised and minority groups such as beatniks, hippies, punks, gangs, and gays have been able to identify one another and bond based on certain clothing and accessory choices. Fashion statements are often anti-fashion statements. Seattle rockers didn't wear flannel shirts because they were fashionable; they wore them because they were practical and cheap. L.A. street kids wear Hanes tank tops because they're sexy and cheap.

Whenever a distinctive look, culture, or type of music becomes marketed on a mass level, it loses its impact. By its very nature, mass marketing mutes complexities. When we appropriate the styles of classes or cultures other than our own, respect and understanding are rarely part of the exchange. We can dress up like part of a rebellious group without taking any of the risks or truly understanding its mindset. Short of ignoring the trends, there's no easy way around this. But being conscious of the ways in which the fashion industry sells marginalized cultures' styles is a start.

[ Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

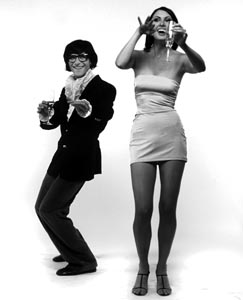

Trend Friends: Tommy Stinson, former bassist for the Replacements and front man for the band Perfect, and model Mandy cavort as thrift grifters.

From the December 31, 1997-January 7, 1998 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.

![[MetroActive Arts]](/gifs/art468.gif)