![[MetroActive Arts]](/gifs/art468.gif)

[ Arts Index | Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Last Laugh

Good grief! The comics page loses a unique voice as Charles Schulz retires.

Schulz's wistful pessimism kept 'Peanuts' going strong for decades

By Richard von Busack

IT'S SAID that the two most popular subjects for a comic strip are funny animals and demon children. In a sense Peanuts, which on Jan. 3 is ending its almost 50-year-long daily run, follows the usual blueprint. The comic strip contained the adventures of one of the funniest and most fanciful animals in the comics--the great dreamer Snoopy. It starred children who, while not supernatural, were almost unnaturally wise, especially the perennial second-bester, Mr. Failure Face, Charlie Brown.

Until the news of Schulz's battle with cancer and impending retirement, the strip sat unobtrusively in its corner, a patriarch with a hundred descendants. It's dizzying to enumerate them all, like all the begats in an Old Testament.

Snoopy begot the fanciful Calvin and Hobbes. Charlie Brown's zigzag shirt was grafted by Matt Groening onto the twin backs of Akbar and Jeff in Groening's Life in Hell--and where would Groening's The Simpsons be without the example of Peanuts? There never would have been a Bart Simpson without Charlie Brown, anymore than there would have been a Lisa Simpson without Linus.

And, on a less wholesome note, would we have had the little round-headed kids in South Park? Where would TV's Seinfeld have been without the example of this comic strip about, in essence, nothing? Throughout the last 50 years, Schulz's characters were prototypes of people, too, life copying art, as Wilde predicted.

Lunch with Charles Schulz

Charlie Brown prepared the world for Woody Allen and for the Nurturing Male. Linus was the ultimate Northern California transcendentalist. Lucy van Pelt--a great comic creation, overshadowed by the others--is a prime example of the novice feminist, infuriated at being patronized, but still claiming all the rights and privileges due to a princess ("I believe in me! I'm my own cause!" she once shouted).

Peanuts always was a still, small voice--a conscience--in the midst of much gimcrack, much junk, much market-driven ephemera. What's happened to the comic page reflects the way that the daily newspaper has changed, from a locally owned part of the community to a division of a communications company.

It's hard to imagine something like Peanuts starting today. Schulz began his strip when the daily paper was full of terrific draftsmen, such as Milton Caniff and Al Capp, and so it might be embarrassing for him to have his artwork praised. But today, when barely anyone in daily comics can draw, Peanuts is one of the best-looking comics on the page. Who else has such breathtaking cleanness of line, such expressiveness, reduced after years of labor into the divine simplicity of Matisse?

A year ago, I was writing about Schulz because the passing of some movie greats had reminded me that artistic immortality didn't coincide with the real thing. Also I wrote a letter to Schulz when I was 6, and it was promptly answered. I still have the letter 35 years later. It was a lesson to me that the people whose work I loved were approachable.

Despite what you may have heard, it's a good idea to express your appreciation to the artists who have meant a great deal to you. I also wanted to write about Schulz because he was a veteran. Much of the World War II nostalgia, rampant after Saving Private Ryan, hadn't acknowledged the other side of what life had offered the veterans--the disappointment that's tangible in some of my favorite art forms: film noir, postwar American novels, '50s jazz, and, of course, Peanuts.

As the old soldiers were passing, we were losing the memory of how the soldier's glory was tinged with disillusionment. And Peanuts always had an undertone of disappointment that made it a revelation in the midst of so much booster culture.

Most, I think, remember Schulz's humor and invention--the kite-eating tree! Linus' blanket, alive and on the prowl, like the Blob! That ineffable look of happiness on Lucy's face when she'd pull the football away! That canine Xanadu, Snoopy's doghouse! But the comic invention of Peanuts sometimes eclipsed Schulz's wistful pessimism. I think it was the sorrow in Peanuts that found an answering chord around the globe.

Now that Schulz is heading into a much-deserved and much-lamented retirement, we can see what the end of his 50-year run means. Charles Schulz made his fortune out of empathy. He made a world-famous name because of a natural sympathy for the underdog.

In short, when Peanuts comes to an end (the last daily strip runs Jan. 3; the last Sunday strip runs Feb. 13), it ought to be remembered that Schulz's kind of sympathy was once considered a national virtue in America--a virtue that has, I fear, been mislaid somewhere along the line.

[ Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

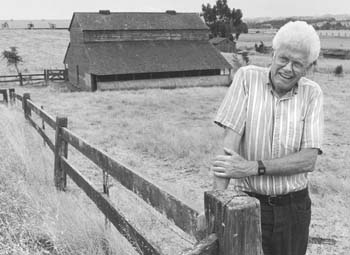

Photograph by David Licht

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

From the December 30, 1999-January 5, 2000 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.