![[MetroActive Features]](/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | Sonoma County Independent | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Miracle Factory

Text by David Templeton

BEN IS NOT HIMSELF TODAY. He looks the same as ever--tall for his age, lanky and lean. But as Ben steps from the van that will return him and several of his 20 brothers and sisters to the homeless shelter in a few hours, the 12-year-old is sullen, withdrawn, clearly preoccupied. His million-dollar smile is gone; there's little sign of the enthusiastic and energetic young man that Ben has been carefully, cautiously evolving into over the last eight months.

Trailed by his various siblings, the boy trudges up the concrete steps leading to Kid Street Theatre, the one-of-a-kind youth crisis center headquartered in a long, low, red brick building near Santa Rosa's Railroad Square. Ben pulls open the door and crosses the threshold, where he spies Linda Conklin, the founder and executive director of KST, waiting for him with outstretched arms. Ben's face gives way to a quick, shy grin. His gaze focused firmly on his shoes, he ambles over to receive the hug that Conklin is offering.

"I'm really happy to see you today," she tells him. Ben is not eager to end the hug, and, sensing the darkness of Ben's mood, Conklin is quick to intuit the cause. "Have you seen your mother?" she inquires. He nods. With practiced brevity, he mumbles a few words. He did see his mother, briefly, only yesterday.

A recovering addict, Ben's mother has been in a residential treatment center for six months, and has been allowed only recently to make brief day trips to visit her children.

"Are you missing her a lot?" Conklin asks softly. He nods again--a slight bob of his head. "Would you like to make her a card to tell her you're thinking about her?" He would, and so, teamed up with Jesse, an older boy who's just arrived, Ben heads out to the art tables in the main auditorium, while Conklin turns to hug the next person through the door.

That's the drill at Kid Street Theatre. Anyone who wants a hug gets a hug, and every kid who walks in hears the words "I'm glad you're here today."

Because to Linda Conklin, that's absolutely true.

KID STREET was founded six and a half years ago, on little more than a whim. Seeking to meet the needs of at-risk youth she'd met while volunteering at a Santa Rosa homeless shelter, Conklin--a former teacher with no theater background beyond owning a season pass at the American Conservatory Theater, and recovering from severe brain damage she suffered in a near-fatal car crash--wangled the use of an old warehouse, offering the kids at the shelter a safe place to spend the long summer months. To give the summer some focus, she proposed that the kids put on a full-scale musical show and used up her remaining savings to make it happen.

Eventually other kids from the neighborhood were introduced to the project--some with horrific family backgrounds and bleak prospects for the future. In the process of creating the show, they blossomed; when the day of the performance came--and the seats filled up with appreciative theater-goers--they learned for the first time what it felt like to be a star; and when the summer was over, no one wanted it to end.

"What I learned that summer," Conklin explains, "is that we all need that kind of a break. We all need a chance to feel special. Sometimes getting that break makes all the difference in how we decide to live our lives."

The owner of the warehouse, Hal Musco, agreed. Having observed the kids' remarkable transformations, he generously granted rent-free use of the building so Conklin could continue what she'd started.

Kid Street Theatre was born.

NOW an established private non-profit agency with a small full-time staff and concrete plans to become a chartered school in the near future, KST has expanded significantly on Conklin's original vision. Though the central focus is still on using theater arts as a builder of self-esteem and a door-opener for the hopes of at-risk kids, KST programs now include night-time parenting classes for the parents of participating children, martial arts self-defense training for kids, bilingual tutoring in various subjects, art therapy, and organized music and singing lessons.

Though many of the kids here are homeless, KST is open to anyone at risk of falling short of their potential. Some of the youngsters are from local women's shelters, where they are living with their moms; some are sent by the public school system--where they may be considered "problems"--as a condition of avoiding expulsion; some are referred by the juvenile court systems.

In many cases, these are kids who've met incredible hardship, from sleeping in a cardboard box to living out of a car. One child was forced to witness his sister's death at the hands of their father.

More often than not, KST is the first place these kids have ever felt truly safe.

The theater itself--since moved to another former warehouse, across the tracks on Sixth Street--features a stage, dressing rooms, sound and lighting systems, all donated or built with volunteer labor. There is a junglelike garden next door, and a vast auditorium space that serves as art studio, recreation area, library, and living room, all rolled into one.

The atmosphere is positive and decidedly casual: daily staff meetings are held on "the lawn," the grass-green carpet in the main office on which staff members stretch out, often barefoot, in a loose circle. As assistant director Laurie Kaufman works the phone to ask for donations--KST needs everything from money and volunteer hours to food and juice and things like duct tape--she laughs often, an infectious sound that often sets the kids to smiling themselves.

But the work done here is serious business. Everyone is expected to pull his or her weight, to function as part of a team. That's not as easy as it sounds for some of these boys and girls. Teamwork is not a concept that has been valued out on the streets, where survival often depends on maintaining a distrustful and suspicious nature.

Since the kids come from such unstable backgrounds, every day at KST is a potential roller coaster of emotion, for the children as well as the staff and volunteers. The effort pays off in the miraculous transformations that routinely take place within these walls, as kids who've been taught, by the circumstances of their lives, that they are expendable, begin to realize that their lives do, in fact, have value, that their futures still hold incredible promise.

"The truth is, there's drama here every day," Conklin says, "but it's usually not on the stage. I've seen it over and over. And I'm not exaggerating when I say that Kid Street Theatre is a miracle factory.

"I heard someone say, not too long ago, 'Imagine if the world worked.' And I thought to myself, I can't imagine it not working. Because I live inside a world that works every single day."

EACH SPRING and at Christmas, the miracles begin to multiply exponentially at KST, as the kids' energies and imaginations are poured into the creation and presentation of a brand-new show. Written by a group of kids and staff members, the shows are developed from ideas shared during "circle time," KST's daily group-therapy sessions in the auditorium.

This year's show is The Christmas Wish, based on several conversations about Christmas--how "left out" the kids feel, how empty is a donated Barbie or Tonka truck on Christmas, when the child's truest needs are for a house, a safe home, a mother released from jail, the return of a father who has run off or been killed, or a family in which to feel loved and protected. To illustrate that point, the kids came up with a story of a Santa Claus obsessed with giving toys, whose elves go on strike to protest Santa's refusal to read the children's letters anymore. With the help of his guardian angel, Santa comes to realize that some people have needs far deeper that anything that can be pulled from a shopping bag.

Thinking up the story, though, is just the easy part.

What will follow is two months of often grueling work, in which emotions and already fragile self-images will sometimes be pushed to their growing edge. The kids will be asked to communicate and cooperate at a high level, to make a series of commitments and honor them, and finally, to put themselves in front of an audience of strangers. These are complicated requirements for some of the KST kids, requiring them to tap into deep inner resources that, until then, few people--including themselves--ever believed they possessed.

After three weeks of rewrites and brainstorming, the script is complete, and casting has begun. Chandra Larsen, KST's program director, is going over the parts with a circle of kids and volunteers, as the play's director, Lois Codding, looks on.

Conklin drops in to give everyone a pep talk. Every seat in the house will be full, she tells them, come "curtain time" on Dec. 12. "Those people are coming to see you," she says. "Because they know how special you are. They know that all of you are stars."

She turns her attention to Jack, a teen who's been at KST since the beginning and is in charge of the lighting crew this time out. Jack lives where he can, since his mother, a working prostitute with a drug addiction, is seldom in the picture. His story stands as a perfect representation of Kid Street's many success stories. When Conklin first encountered him, he was angry and defensive, suffering from severe emotional damage, and failing in school. On top of that, Jack was diagnosed with a debilitating eye disease that often results in blindness.

A fierce child advocate, Conklin personally meets the teachers of all the KST kids. When a school counselor once referred to Jack as "a waste of human life," Conklin wasted no time in reporting her. "I can't tell you how angry that made me," Conklin says. "No kid is a waste of human life."

For several years Jack came to KST refusing to lower his defenses. Finally, during a round of the box game--in which half-completed statements are randomly drawn from a box and the participant must complete the thought--Jack pulled the phrase "One thing I've realized is ..." Conklin remembers bursting into tears when he answered, "I realize I've been a jerk. Opportunity has been knocking on my door for four and a half years. I think I'm ready to answer the door."

Asked what changed for him, Jack replied, "I finally believe that you really do love me." For the last two years, Conklin has arranged for Jack to attend a camp for the blind and has worked out the details for him to receive medical care. Conklin reveals there is even hope now that Jack's eyesight can be saved.

FORMAL REHEARSALS for this holiday season's show begin, and volunteers start to show up to construct scenery. The kids repeatedly practice the song that will close the show, Burt Bacharach's "That's What Friends Are For." As the weeks and days count down to show day--and the excitement and pressure continue to build--many of the kids experience some intense feelings, as their fears and frailties, their hidden hopes and expectations, rise ever closer to the surface. Then, during the final dress rehearsals, a kind of therapeutic release occurs. There are tear-filled events every few minutes. When Joe--staying with his mom and sister at a halfway house for abused women--cannot remember his lines, the frustration reaches deep into his fear-filled young life. Jane, fully dressed as a tiger, suddenly refuses to go on stage.

Another kid, playing a lion, freezes up just before his big entrance and, frozen, cannot move on or off the stage.

A visitor, observing the volatile eruptions of genuine emotion, remarks that it seems unlikely a show can ever be pulled together in time. But this is all part of the Kid Street process. And no matter how chaotic the situation may seem, there is never a lack of hugs and warm guidance whenever tears begin to fall or sudden fears arise.

An underlying philosophy--that every breakdown is a potential breakthrough--seems to be proving itself true all through the room.

And it's not over yet.

ON THE DAY of the performance, the kids are excited, but incredibly focused. Hundreds of paying guests have arrived--many of them having attended every KST show since the beginning--and the room is buzzing with electricity.

"I wouldn't miss this for anything," says Joan Betts, a longtime KST supporter. "I've watched these kids for years. I've watched the changes happen, and I'm telling you, coming out of this program, these kids will be leaders."

When Conklin breezes in to announce that the play is about to begin, Betts adds, "She's a powerhouse. She knows how to get the right people together. But most important--she knows what love is. She knows how to love these kids."

Backstage, it appears that the previous days' emotions have given way to a profound combination of peacefulness and a hard-earned sense of pride. Given a cue, the cast files calmly out front to take seats of honor--as Conklin makes opening remarks. She turns first to the kids.

"Remember when I told you guys how special you were?" She asks with a grin. "Remember that I said we would fill this place up? Well, look around you. This is all because of you." Turning to the standing-room-only audience, she says, "When these kids walk through the door, they are all considered geniuses. They are reminded that they are capable of great things. They're so excited to be treated that way.

"It's amazing how many of them have risen to the occasion in putting together today's show."

With that, The Christmas Wish begins.

By the time the performers each have come out to announce their own wish, there are few dry eyes in the house. The few holdouts have an even harder time resisting tears when the entire cast and crew join hands to sing: "Well, you came in loving me,/ and now there's so much more to see,/ and so by the way I thank you./ Keep smiling, keep shining,/ knowing you can always count on me, for sure,/ that's what friends are for, for good times and bad times,/ I'll be on your side for ever more,/ that's what friends are for."

As applause thunders through the room, Conklin gleefully shouts to the others onstage, "You earned this applause, guys. So take your bows. You deserve it."

It's been a tough couple of months. And no one is kidding anyone--the tough days for these kids are far from over. But once again, under the gaze Linda Conklin's unconditional high-esteem, they've learned they can surmount difficult circumstances to create a thing of beauty. They've learned that anything is possible.

Still holding hands and now beaming, the kids of Kid Street Theatre take their bows.

[ Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Hard-knock kids find a place where dreams are reborn

Hard-knock kids find a place where dreams are reborn

Photos by Michael Amsler

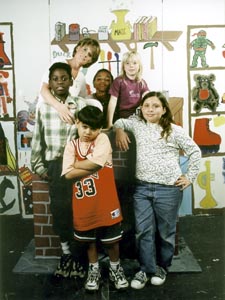

Million-dollar smile: Ben, a homeless child who first came to Kid Street Theatre eight months ago, has blossomed, thanks to the unconditional love of the KST staff.

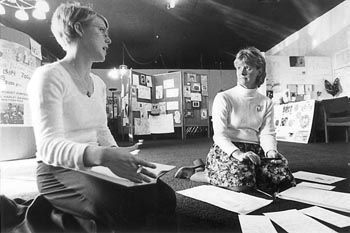

A new beginning: The creation and presentation of a new play at Kid Street is an eight-or nine-week process that will demand incredible levels of commitment from the kids involved, already facing unimagin-ably harsh challenges in their lives. A powerful process of guided expressive therapy and straightforward group discussion begins and ends every day at KST, allowing the kids to identify and work through some of their darkest feelings. The result--as hidden feelings are brought to the surface--is often intense. Jay is comforted by program director Chandra Larsen.

Jay is comforted by program director Chandra Larsen.

During "circle time" the boys and girls, many of them in their teens, will decide the theme of this year's play. From an open-hearted discussion of how much many of them dislike Christmas--already a difficult time for the haves of the world, and often nightmarish for those who have nothing. After a group exploration of the things they'd truly like for Christmas-- a house with a chimney, a sister, to be safely off the streets, a long-absent parent to be returned to the family--the title of the play is decided: A Christmas Wish. Success stories: The involvement of parents, when possible, is an important aspect of Kid Street. Molly was failing at school, academically and socially. Her mother, a struggling addict, has long been absent, so she lives with her father. When he began attending weekly parenting classes, Molly's dad began a transformation of his own. After admitting he'd never learned to read, he began taking adult literacy classes at the junior collegeand is considered a model parent at KST. As for Molly, after several months at Kid Street, she's made a remarkable reversal, and is now in the top three percentile of her school.

Success stories: The involvement of parents, when possible, is an important aspect of Kid Street. Molly was failing at school, academically and socially. Her mother, a struggling addict, has long been absent, so she lives with her father. When he began attending weekly parenting classes, Molly's dad began a transformation of his own. After admitting he'd never learned to read, he began taking adult literacy classes at the junior collegeand is considered a model parent at KST. As for Molly, after several months at Kid Street, she's made a remarkable reversal, and is now in the top three percentile of her school.

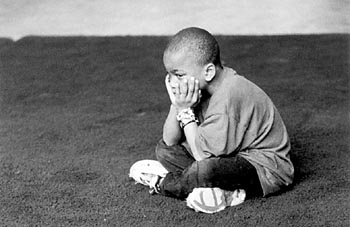

Transition: During a group-therapy art project on the theme of "safety," Daniel, alternates between sweet-spirited gentleness and sometimes startling displays of anger and self-destructiveness. He is asked to draw a picture of what he might do to feel safe. Safety is a core issue for Daniel, who resides with his mother in a Sonoma County shelter for abused women. "He is in constant survival mode," says Linda Conklin.

Rather than using the markers to color his paper, Daniel draws bright-red gashes--a "superhero mask," he says--across his face. When a therapist shows Daniel his reflection in the mirror, the child shakes his fist defiantly; the process has tapped a deep well of emotion in the boy. Before the day is over, he's found a lap to cry in, and then returned to his formerly buoyant self.

Meanwhile, Billy--Ben's younger brother--chooses to sit by himself after learning that he will not be playing the part he'd hoped for in the upcoming play.

Laying the ground rules: During rehearsal, Ben can't seem to concentrate."You made a comitment to be in this play, remember?" says program director Chandra Larsen (left with Linda Conklin). "When you make a commitment, you have to work hard to keep it."

As the performance nears, the process is producing the anticipated emotional upheavals in the kids. Before it's over, a handful of the kids, including Ben, will be cut from the show--all part of KST's tough-love approach. "This is no welfare system," Conklin says. "In here you get what you work for."

When Ben's mother--out on a day pass from the rehab center at which she lives--visited Kid Street, she couldn't stop crying. "I'm so ashamed," she said. Conklin responded by telling her that everyone at KST was proud of her. "There are kids here who say, 'I wish my mom or dad would go into rehab.' Your children are proud of you," she softly added. "In their eyes, you're a hero."

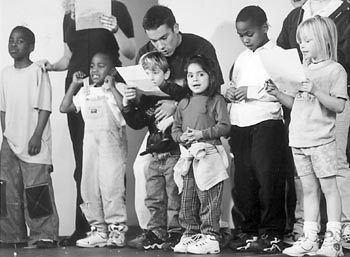

Crunch time: Emotions are in a state of upheaval by the time of the "parents only" dress rehearsal: Shelby, diagnosed with attention deficit disorder, arrives at the theater in an advanced state of agitation, having earlier been given a double dose of ritalin.

Ellen, 9 years old, tells Conklin that her mother is in jail and her custody will be transferring to her father. Diane, whose 16th birthday is tomorrow, has just been informed by her father that he plans to give her up for adoption. In spite of the unimaginable stress they are under, the cast--minus a few members who dropped out at the last minute--manages to maintain a remarkable sense of focus. By the time they've reached the play's end--and each child stands center stage to inform the audience of his or her most earnest Christmas wish--they've pulled it together and put on a magnificent show.

On the rebound: Billy, after bouncing back from his disappointment at having to play an elf, likes what he sees after visiting the makeup table, and throws himself into the part. His enthusiastic recital of "Let's go on strike!" and "Let's go to Hawaii!" will end up warming the hearts of the audience on show day.

Christmas wishes: After weeks of hard work, the kids of Kid Street--some homeless, some abused--have reached the big day. The show goes off without a hitch; as Conklin promised, the kids are all brilliant. Then, before a brightly painted set depicting Santa Claus' toy shop, the performers each take their turn center stage, many holding the hand of an accompanying adult or friend, to name the one thing they most wish for this Christmas. "My wish is to see my mother again"; "I wish my Mom could be here today"; "I wish my family could be all together"; "My wish is to have a house with a chimney"; "My wish is that my Mom would call me on Christmas and tell me she loves me"; "My wish is to be safe"; "My wish is that this could be my family."

The show goes off without a hitch; as Conklin promised, the kids are all brilliant. Then, before a brightly painted set depicting Santa Claus' toy shop, the performers each take their turn center stage, many holding the hand of an accompanying adult or friend, to name the one thing they most wish for this Christmas. "My wish is to see my mother again"; "I wish my Mom could be here today"; "I wish my family could be all together"; "My wish is to have a house with a chimney"; "My wish is that my Mom would call me on Christmas and tell me she loves me"; "My wish is to be safe"; "My wish is that this could be my family."

When Conklin later joins the kids onstage, she tells the deeply moved crowd, "When I first asked these amazing kids what they wanted, it was incredible to hear the things they wished for. I didn't hear a lot of toys and stuff mentioned. What they asked for are things we all take for granted every day." Then, surrounded by the remarkable family of Kid Street Theatre, she adds, "We've shown you today that it's possible to make miracles. Now it's up to you to go out and make some miracles of your own."

Kid Street Theatre, a non-profit agency located at 54 West 6th St., Santa Rosa, is accepting donations ranging from cash to duct tape. Volunteers are welcome. For details, call 525-9223.

From the December 24-30, 1998 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.