![[Metroactive Books]](/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | North Bay | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

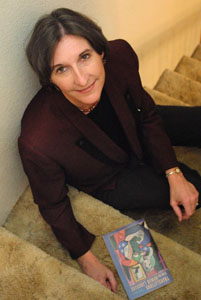

Photograph by Michael Amsler

Painting in Tongues

Poet Terry Ehret masters the art of words

By

Terry Ehret talks in pictures. An award-winning poet and teacher, Ehret is a master at using words to create vivid images. Even in everyday conversation, delivering remarks in a tone of voice as subdued and noncommittal as a plain, white canvas, Ehret illustrates her speech with ideas that are achingly visual.

Ehret--author of the collections Suspensions and Lost Body, and a writing teacher at Sonoma State University and Santa Rosa Junior College--offers memories and insights so sharply sketched that they hang in one's mind for hours afterward.

This crisp December morning, for example, in the midst of explaining how dangerous it can be for a poet--for any of us, really--to try to escape the behavioral models we create for ourselves, Ehret begins describing a large window that once looked out from the house of her childhood, a piece of plate glass so wide that from the outside it reflected only a vast expanse of sky.

"Birds would fly toward the window and would fly right into it," she recalls, "because all they would see in it was more blue sky. Our backyard was full of the graves of broken-necked birds."

What Ehret's readers have known for years (and what her students quickly learn) is that after reading her words or listening to them, you begin to see the world differently. You start to notice things.

"And that," she says with a nod, "is what poetry does to you."

Today, Ehret is perched on the couch in the Petaluma home she shares with her husband and three daughters. She's cradling a warm cup of Earl Grey tea--it's an Earl Grey morning; the tea's color perfectly matches the sky outside the window--and describing the experience of creating her newest book.

Titled Translations from the Human Language, this volume represents more than just her first solo work since the 1993 release of Lost Body. The new book also marks Ehret's entrance into the world of publishing.

Released in August, Ehret's Translations and a collection of poems by San Francisco poet Valerie Berry, Difficult News, are the first books to be published by Sixteen Rivers Press, the innovative not-for-profit publishing collective cofounded by Ehret.

Sixteen Rivers--named for the 16 rivers that flow into the Francisco Bay--is based on a model pioneered by Alice James Books, a feminist poetry cooperative started in Maine in the 1970s as an alternative publishing avenue for women writers.

Ehret first learned of collective publishing in June, 1996, while attending a writing workshop in Oregon. During a group discussion on the difficulties of getting poetry published, Ehret shared her own frustrations, revealing that each year she allowed herself $500 dollars to spend on contest fees, mailing costs, and the like. In spite of numerous awards and previous books published, she seldom saw any return on her investment.

Said Ehret, "If a group of writers pooled the money they would normally spend in a year to not get published, they could probably afford to publish one or two of their own books."

Afterward, she was cornered by Ruth Gundle, founder and editor of Eighth Mountain Press, who told Ehret that what she had just described was called collective publishing. Gundle quickly put Ehret in touch with Patricia Cumming, one of the founding members of Alice James Books.

An excited Ehret brought the idea to her Sunday evening writers group. The theory was simple: Members would make an initial investment of cash and commit at least a few years to the collective. Each member would take turns performing all the tasks of a publishing company, from typesetting and designing to marketing and distribution.

Nobody took the bait.

Not until 1999, after years of letting the idea ferment in her mind, was Ehret able to assemble a group of poets willing to take on the challenge of forming a regional press. By that time, Ehret had won the support of Gundle and Cumming, along with established writers such as poets Dana Gioia and Carolyn Kizer and sci-fi legend Ursula K. Le Guin, who all agreed to act as advisors to the publishing collective.

With a total of eight members, an official name, and a sharp new logo, the group decided they would publish two books a year, starting with those members who had manuscripts ready to go--four of them did--and pairing one established poet (a writer who'd already been published) with one newcomer.

The decision about which authors would go first was made in charmingly egalitarian fashion: Collective members drew names from a hat. As it turned out, Ehret and Berry went first, to be followed the next year by Margaret Kaufman and Susan Sibbet.

For Ehret and Berry, whose starting position left them feeling alternately like pioneers or guinea pigs, the process of turning their manuscripts into books was harder than they had guessed. Still, these first two books from Sixteen Rivers made it to press and reaped immediate critical acclaim from such publications as Poets and Writers.

"It represents a quantum leap in our view of ourselves," Ehret says. "Because now, all of a sudden, we're thinking of ourselves as a publishing company, where previously we just thought of ourselves as writers who had some collective experience."

Ultimately, of course, the success of Sixteen Rivers will depend on the quality of the books it publishes. While the 50-something poems that comprise Translations from the Human Language represent less than a quarter of the work Ehret has produced since publishing Lost Body, she feels they are among the best she's ever written.

"My feeling is that these poems, together, make a statement that is larger than the statement they make alone," Ehret says.

The poems in Translations have much in common with Ehret's previously published work in that every piece in some way reflects the author's obsession with the secret vernacular that lies behind language, those portions of our lives that are not verbal but are communicated through body language and tone of voice.

"What I mean when I talk about the human language," she says, "is that which lies beneath spoken and written language. Because those silent rituals are as potent, as piercing as anything that is verbally expressed, and . . . . "

With that, Ehret grows silent. She turns her head and gazes outside and up toward the sky, as if to wordlessly add, "And as powerful as a refection on a plate-glass window."

[ North Bay | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Poet & Publisher: Terry Ehret joined forces with other local poets to form Sixteen Rivers Press.

Poet & Publisher: Terry Ehret joined forces with other local poets to form Sixteen Rivers Press.

From the December 13-19, 2001 issue of the Northern California Bohemian.