Easy Target

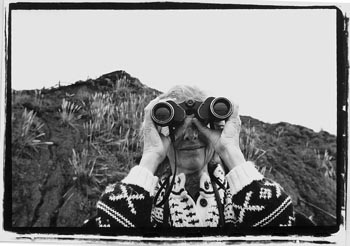

Eye on the Prize: For the past seven years, Elinor Twohy has kept daily watch on California sea lions and Pacific harbor seals basking near her Jenner home. Now federal wildlife officials blame the peaceful pinnipeds for dwindling fisheries.

Federal wildlife report proposes selective slaughter of local seals and sea lions

By Paula Harris

AFTER A NIGHT of hunting in cold deep waters, several Pacific harbor seals haul their hefty mottled bodies onto the sandbars at the mouth of the Russian River to rest awhile. Visitors may be attracted to their doglike, whiskered faces and large liquid eyes, but few onlookers are aware that these pinnipeds, along with local sea lions, are facing a possible culling next year.

A draft Report to Congress on the Impacts of California Sea Lions and Pacific Harbor Seals on Salmonids and West Coast Ecosystems headed for Capitol Hill next year seeks to reauthorize the Marine Mammal Protection Act and give authorities permission to shoot troublesome seals and sea lions. If sanctioned, the cull--which raises the spectre of marksmen sniping the peaceful sea mammals reclining near Jenner--could cover 52 river systems in Washington, Oregon, and California, including the Russian River, where coho salmon and steelhead trout have been placed on the threatened-species list.

According to some beleaguered fishermen, the Pacific harbor seals and California sea lions are largely responsible for the demise of the fish species. Activists disagree.

Federal fisheries managers claim that evidence supports the long-held contention of local fishermen, since sea lion and seal populations are thriving while endangered/threatened salmon populations are diminishing. The feds say that the burgeoning numbers of seals and sea lions are indeed partly to blame.

If the recommendations of the report are approved by Congress, by this time next year state Fish and Game and federal Fish and Wildlife officials could be stationed at the overlook on Highway 1 above the Russian River to observe the winter run of steelhead salmon. If they see seals or sea lions preying on the fish, they could be authorized to shoot to kill. "The implications are enormous," says Dian Hardy, founder of the Seal Watch program, which guards resting seals against onlookers north and south of the Russian River in cooperation with the state Department of Parks and Recreation. "It will be the first time the Marine Mammal Protection Act will be breached to allow government intervention."

SEALS AND SEA LIONS are currently protected under the federal Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972. "Before that, they were hunted with impunity, and it looks like we're on the road to return to that bloody time," laments Hardy.

But Chuck Wise, president of the Fishermen's Marketing Association in Bodega Bay, says something has to be done to control the animals. "They are growing 5 to 10 percent on a yearly basis, and they can't continue to do so unchecked," he says. "Otherwise there's not going to be a fish left in the ocean and the beach will be littered with sick sea lions."

Wise says that he encounters the large sea mammals, especially sea lions, more now than at any other time in 25 years of fishing. "I realize [sea lions] are doing what comes naturally, but they go around in packs now and we're lucky to get 50 percent of the fish that get attached to our gear before [the sea lions] get them."

Environmentalists say a 1991 scat analysis study at Russian River showed that salmon is not the primary food source for seals, which mostly eat flat fish, octopus, hake, and hagfish. Sea lions are known to consume a similar diet of squid, octopus, herring, rockfish, mackerel, anchovy, hake, and lamprey. Environmentalists say the pinnipeds are being scapegoated for other, more damaging factors, such as the recent human impact of clear-cutting, dredging, damming, and pollution that have caused the decline of the state's fisheries.

Elyssa Rosen, California regional representative of the Sierra Club, says the destruction of habitats is caused by landowners upstream, not by sea mammals at the mouth of the river. "If they're going to be taking it out on the sea lions, it's misguided--the real problem is the industrial timber practices and the practices from water development and from agriculture, mainly wineries," says Rosen. "Timber practices may be the No. 1 impact on salmon fishing. It's a big, nasty business that continues to operate without restrictions. Sea lions certainly aren't the culprit."

Tom Okey, marine biologist and Pacific fisheries project manager for the Center for Marine Conservation in San Francisco, agrees. "The real reason is it's our modification and they are the scapegoat--seals and sea lions are potentially having an effect on the salmon population because we've modified habitats. It's our fault," he observes. "We've changed rivers, whole watersheds, and forests. If you change temperatures, sedimentation of rivers from grazing, or agricultural activities, or pollution runoff, then agricultural or industrial areas will all contribute to the habitual degradation of salmon."

Wet & Wild: Salmon not on the menu.

THE HUMANE SOCIETY is strongly opposing the recommendations for site-specific lethal management of California sea lions and Pacific harbor seals. After reviewing the data, Toni Frohoff of the Humane Society notes: "We strongly believe that sea lion predation is not responsible for the decline of fisheries along Washington, Oregon, and California and that it is crucial that managing agencies mitigate the true sources of the declines.

"We believe that this [culling] proposal will do nothing to improve or enhance the salmon population, but will further its demise by diverting attention from the actual causes: habitat loss and mismanagement of the fishery. Pinnipeds and salmon have co-existed on the West Coast for millions of years. This proposal is unable to cite any scientific studies to support its thesis because there are none. Therefore it is irrelevant and should be abandoned in favor of meaningful solutions based on solid scientific evidence."

Irma Lagomarsino, fishery biologist for the National Marine Fisheries Service, southwest region, who helped write the controversial report, says that although the NMFS has concluded that sea lions and harbor seals have not caused salmon to become depleted or endangered, they may inhibit growth of the salmon population.

She admits that several factors have contributed to the decline in salmon, and that although seals and sea lions are not a major contributing factor, "they could contribute to [salmon] populations not recovering."

The report recommends that state or federal workers could be authorized under strict guidelines to "lethally take" seals and sea lions in cases where the pinnipeds are preying on salmon; impeding passage of salmon; or in cases where certain individual seals or sea lions are not responding to non-lethal deterrents and are becoming a burden to fisheries, causing a significant economic impact.

Lagomarsino says all these "management strategies" would restrict the number of "lethally taken" pinnipeds annually. "The PBR [potential biological removal] idea is to remove a few animals every year, and we would not allow more to be taken over the PBR," says Lagomarsino, adding that the combined PBR for Washington, Oregon, and California would be 6,410 "lethally removed" pinnipeds per year. "But maybe only a dozen or two dozen would be removed. We don't anticipate it would come close to the PBR--it just won't happen."

When asked whether sea lions and seals are being scapegoated, Lagomarsino pauses for a few moments before answering. "The agency's perspective is that's not the case," she finally says. "That's why we came up with those recommendations." The NMFS is looking into more non-lethal deterrents--such as seal bombs, barriers, and blunt arrows--but environmentalists say a lot more research needs to be done in that area. The NMFS is wading through 3,000 public responses about the draft report, and the final version won't go to Congress for a couple more months.

Meanwhile, Hardy says that in the 13 years she has worked closely to harbor seals she has never felt so threatened as by the proposed culling policy. "An unnatural predator will have a license to kill," she says, shaking her head. "Natural order will be turned on its head by this."

If the proposal goes through, she adds, Seal Watch plans to continue protecting the pinnipeds. "If necessary, we will put our bodies on the line," says Hardy. "Because the empathy you develop for these animals, so awkward on land, is strong. In their vulnerability, I see an echo of our own selves--we're also awkward land creatures."

[ Sonoma County Independent | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

Michael Amsler

Michael Amsler

From the Dec. 4-10, 1997 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.

![[MetroActive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)