![[MetroActive Books]](/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

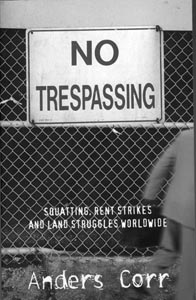

'No Trespassing' makes the case for do-it-yourself housing

By Patrick Sullivan

IN A WORLD full of uncertainties, there is one thing you can count on: Throughout the gloriously compassionate holiday season, an army of TV reporters will converge on homeless shelters around the nation, eager to shed a few prime-time tears over the plight of those who can't afford a room of their own.

We watch all this with a mixture of pity and apprehension. As rental rates and housing prices reach towering new heights across the Bay Area, it's easy to imagine that only a few paychecks stand between us and life on the street--or at least life with our parents.

If we were turned out of our cozy little digs, perhaps we could take some comfort in the fact that we would be far from alone. Or maybe not. In any case, around the world, some 100 million people are homeless and 1 billion endure inadequate housing. Very sad: but what can anyone do? Anders Corr, author of No Trespassing (South End Press; $17), has an answer, but it's not one landlords are going to like much.

The book, subtitled Squatting, Rent Strikes, and Land Struggles Worldwide, makes no secret of its sympathies. The Santa Cruz-based author, who was himself briefly a squatter, takes a wide-ranging look at people who take over vacant buildings and unused land, from punks to peasants, from poor farm workers in Honduras who squat on an unused banana plantation to advocacy groups in San Francisco who open abandoned buildings to the homeless, to some guy who builds a teepee on a winery in Sonoma.

Corr's conclusion? Squatting is usually a darned good idea.

There will be some, of course, who object to squatting on moral principle, reasoning that lazy losers shouldn't violate the rights of those who have worked hard to own property. For them, Corr has assembled an impressively reasoned answer. In part, he argues that squatters are often hard-working people driven to the margins by a ruthlessly competitive (and often illogical) world economy and left homeless by societies that would rather leave buildings empty than give someone a roof over his or her head.

It's an especially compelling argument when it's applied to the Third World, where land can literally mean the difference between life and death. Corr tells the monstrous story of how United Fruit, now Chiquita, amassed a huge portion of the arable land in Honduras, the quintessential banana republic. The company employed all kinds of chicanery, twice engineering the overthrow of the national government to get and keep land. In the face of that, it's hard to condemn the efforts of laid-off banana workers to set up farms on company land.

But Corr does more than argue in favor of squatting. In this impressive piece of radical scholarship, he shows what makes squatters tick, why they win, and why they lose.

You're guaranteed to read about events that were somehow overlooked in history class, including the astounding tale of the largest rent strike in U.S. history. In 1975, most of the 80,000 residents of Co-Op City, a huge public housing project in the Bronx, collectively stopped paying their rent to force their landlord, the Riverbay Corp., to roll back a huge rent increase. After a 13-month struggle, the tenants won major concessions.

Then there's the astonishing case of an African-American farmer named Oscar Lorick, who faced eviction from his Georgia farm in the mid-'80s. With nowhere else to turn, Corr explains, Lorick crafted an unlikely alliance with a group of Christian Identity-style racists, who showed up with semiautomatic weapons to defend the man's farm from the evicting sheriff. For these white supremacists, the all-too-familiar plight of a man being thrown off his land by a bank mattered more than their racist beliefs.

A word of warning: No Trespassing is often painfully earnest. At times, you'll want to take this book by the lapels, give it a shake, and beg it to tell a joke or throw in some color.

Still, there is more than enough compelling drama and astute analysis here to reward the patient reader. And, of course, Corr would probably argue that a serious subject demands serious treatment. After all, what's more important than good housekeeping--especially if you're making do without a house?

[ Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Squat or Rot!

Squat or Rot!

From the December 2-8, 1999 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.