![[Metroactive Movies]](/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | Show Times | North Bay | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

Autumn Leaves

If costume and art direction were everything, Todd Haynes' 'Far from Heaven' would be celestial

By Richard von Busack

Fall has brought us a bumper crop of movies soaking in the era of the Hollywood studios--it's been film-geek city with the MGM chiffon of Punch-Drunk Love and 8 Women. Now comes the most elaborate pastiche yet: Todd Haynes' Far from Heaven, which attempts to re-create the colors, mood, and melodrama of the autumn leaf blowers director Douglas Sirk turned out in the 1950s.

Sirk (1900-1987) did his share of genre work, including detective and Western movies. He's best known, however, for his women's pictures, such as his class-conflict romance All That Heaven Allows (1955) or his tragic-mulatto drama, the remake of Imitation of Life (1959). Sirk's influence can be seen everywhere from Fassbinder's melos to John Waters' carnivals of crime.

Haynes (Velvet Goldmine, Safe) has spun his film off the race relations of Imitation of Life and the romance between an affluent woman and a man of the soil in All That Heaven Allows. Far from Heaven does seem like a Sirk movie for a new century--the same satiny style but with more adult subject matter.

Julianne Moore plays Cathy Whitaker, a housewife in suburban Connecticut in the late 1950s. She has two children who are as perfectly kept and perfectly ignored as those in a sitcom: a girl taking ballet lessons and a son whose big problem in life is forgetting to wear a jacket outdoors. Her husband, Frank (Dennis Quaid), pushes himself too hard at work.

This elegant life starts to fray when Frank begins arriving late for dinner and drinking too much. As we follow him, we're privy to his unspeakable secret: He's drawn to other men. Frank wrestles with this "sickness" through booze and visits to a doctor. Meanwhile, Cathy befriends her gardener, Raymond (Dennis Haysbert), who is kind, strong, and thoughtful--and black. This friendship is much commented on by the neighbors. Raging gossip adds to Frank's angst.

Sandy Powell's costumes are glamorous but deliberately stiff. Films in the 1950s starred actors bred to uncomfortable clothes, as today's performers aren't. This discomfort--Moore always seems to be wearing a girdle--adds a layer of meaning to Far from Heaven, but it also adds a layer of rigidity.

All praise is due to Moore and Quaid. It's a mark of Moore's talent that you're never tempted to laugh at her quaintness. Still, Haysbert faced the most difficult task--after all, he didn't have old movies to model his character on. His Raymond is so effortlessly dignified, it's as if he's only heard of the existence of racism as a troubling rumor.

This is an extravagantly beautiful film, including exhaustive contributions by production designer Mark Friedberg, who worked on the similarly dense Ice Storm.

Despite all the remarkable craft, I found it impossible to be swept away on these torrents of unspoken emotion. It sure gives you a turn seeing the age you were born into treated as if it were as far away as Elizabethan England.

Haynes makes the past seem estranged. You're meant to see Far from Heaven and think, "It's been a long time since the 1950s; how the world has changed," when actually the truer thought is that it's been a long time since the existence of a world that never existed except on Hollywood sound stages. The crack between Haynes' formalism and modern issues is always visible. You can see his point, but the point doesn't pierce the heart.

[ North Bay | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

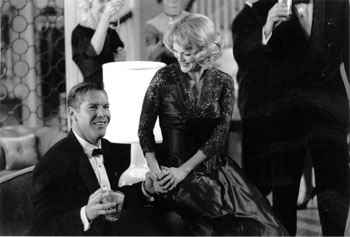

Stiff Drink: Julianne Moore and Dennis Quaid put a good face on their failing marriage in 'Far from Heaven.'

'Far from Heaven' starts Friday, Nov. 15, at Rialto Cinemas Lakeside.

From the November 14-20, 2002 issue of the North Bay Bohemian.