![[Metroactive Music]](/gifs/music468.gif)

[ Music Index | North Bay | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

Bass Motives

Stefano Scodanibbio explores the uncharted terrain of the double bass

By Greg Cahill

Stefano Scodanibbio is not a household name, and unless we all learn how to pronounce it, this avant classical composer and innovative double bassist may remain unknown. "Just one thing," Scodanibbio says during a phone interview from a Southern California hotel room, "Stefano. Accent on the first syllable."

"Oops, sorry."

"That's OK," he offers, "all Americans do it."

That said, understand this: Calling Scodanibbio a bass player is like suggesting that Paganini was a fiddler. Or that Jimi Hendrix was just a guitar picker. Or that Magellan was a cruise-ship captain. "Stefano Scodanibbio is amazing; I haven't heard better double bass playing than Scodanibbio's," the late composer John Cage marveled upon first hearing the musician. "He is really extraordinary. His performance was absolutely magic."

But making magic is hard work. And, during a phone interview from his L.A. hotel room, Scodanibbio confesses to being "stressed" as he prepares for a busy U.S. tour that brings him this week to Sonoma State University. That tour recently found Scodanibbio joining composer and pianist Terry Riley at the ultrahip three-day All Tomorrow's Parties festival, held onboard the Queen Mary in Long Beach. This year, The Simpsons creator Matt Groening curated the indie-music fest, hand-picking Scodanibbio and such other acts as Iggy Pop and the Stooges, Sonic Youth, Cat Power, and the Shins.

Pretty good company.

For a sample of what makes Scodanibbio so special, spin the 2001 recording Six Duos, on which Scodanibbio performs with violist Dov Scheindlin, violinist Irvine Arditti, and cellist Rohan de Saram, the latter two of the London-based Arditti Quartet, those intrepid interpreters of contemporary music. Throughout this haunting release, Scodanibbio can be heard exploring a surreal-sounding microtonal alien world landscaped with what Wire magazine dubbed "exquisite tone, nifty arabesques, and, most importantly, [a] range of percussive effects [that] are all devastating."

Scodanibbio, whose early musical interests ranged from guitar to saxophone, didn't start playing double bass until age 18. He arrived on the scene at the height of the double-bass renaissance, which started in the 1960s when Bertram Turetsky began soliciting solo works from top contemporary composers. "I think that the double bass was the most neglected of the stringed instruments for characteristics that in the past were considered negative--the big body, the length of the strings, the great distance between the notes," he says. "But now those are considered positive characteristics with a wide spectrum of possibilities."

Scodanibbio, who began composing as a teenager, already had a grasp of the fundamentals of contemporary music when he began his double-bass studies at the Rossini Conservatory in Pesaro, Italy. "I also had the good fortune to study with the big European master of concert bass, Fernando Grillo, who after Turetsky in my opinion has been the most important bass player of the past 50 years," he adds.

But it was the book Six Memos for the Next Millennium, a collection of lectures on literary values by postmodern novelist Italo Calvino, that laid the groundwork for Scodanibbio's unique musical philosophy. Calvino's landmark work assigned a series of attributes--lightness, quickness, exactitude, visibility, and multiplicity (a sixth lecture on consistency was preempted by Calvino's death)--that could serve the writer in the 21st century. "These are all attributes that could be transformed to the double bass," Scodanibbio says, "an instrument that until recently was considered to have none of these characteristics."

Over the years, Scodanibbio has developed and refined several new techniques for the instrument. But he regards himself first and foremost a seeker. "All I can say is that all the others are bass players because I don't consider myself 'a bass player,'" he says with no hint of conceit. "My interest in music is not the instrument itself but the composition. I need the double bass simply to express a deep desire that I have within myself to discover something new.

"At first, it was very clear to me that double bass was full of potentialities to be explored--those potentialities were just there, waiting, and they just needed someone to do this job, this dirty job," he adds with a laugh. "At the time, for whatever reason, nobody else wanted that task. So I took it up."

[ North Bay | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

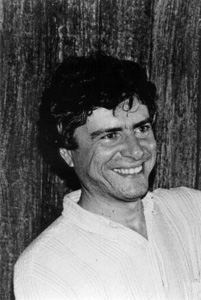

Double Duty: Stefano Scodanibbio's work on the double bass had John Cage swooning with superlatives.

Stefano Scodanibbio performs a solo bass concert on Friday, Nov. 14, at 8pm at SSU's Warren Auditorium, 1801 Cotati Ave., Rohnert Park. $12 general; $8 students and seniors. 707.664.2353.

From the November 13-19, 2003 issue of the North Bay Bohemian.