![[MetroActive Music]](/gifs/music468.gif)

[ Music Index | Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

The Boss's Back

On the other side of Bruce Springsteen

By David Templeton

I WASN'T EXPECTING to go see Bruce this time around. Though my heart rate admittedly quickened when I first learned that Springsteen would be touring this fall--together again with the E Street Band--I'd quickly decided that my time and money had better things to do.

Now, don't get me wrong.

I still consider Springsteen to be the best, most dynamic rock-and-roller standing--an argument I've gotten better at making as the years have flipped by. But the day before Springsteen's Oakland Coliseum concerts went on sale, I figured I would sit this one out.

See, my wife and I have been reading Suze Orman books. We're consolidating our debts, cutting back on non-essentials. How could I justify something as, um, frivolous, as a Bruce Springsteen concert?

The sweet voice of anarchy piped up in the form of my 12-year-old daughter, Amber.

The night before tickets were to go on sale--for a two-night run (later extended to three nights) at the Oakland Coliseum--I discovered a little pile of dollar bills under my pillow, savings from Amber's allowance, with a little note: "Go see Bruce."

"You have to go," she pleaded. "For goodness sakes, you've had the guy's butt hanging on your wall my entire life."

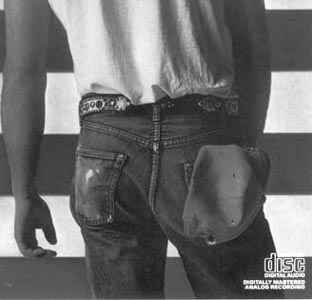

It's true. She speaks of a framed, 4-by-4-foot poster of the Born in the U.S.A. album cover--the one featuring that famous close-up of Bruce's well-worn blue jeans.

Bruce's butt. I've had that poster since 1984. Over the years we've come to know every inch of it, from the missing rhinestone on his belt to the white, Brazil-shaped fade-mark on the left back pocket.

I bought the poster when I was 25, as an adornment to liven the bare walls of the apartment I was suddenly occupying all by myself--after a stinging breakup with my girlfriend. Bruce's Butt became the focal point of my home, a symbol of wounded masculinity. Or something.

Not that Bruce needed such a bachelor-pad exhibition.

With Born in the U.S.A., Springsteen was, at that moment, very, very popular, selling out amphitheaters and making millions. With his surprisingly commercial new collection of three-minute musical snapshots, Springsteen--a strong word-of-mouth favorite since before his Born to Run album put him on the charts--had struck a major American nerve.

I remember a night in late 1984, in a downtown pub populated entirely by the kind of men inclined to be hanging out in a bar at 2 a.m. When the radio started playing "Dancing in the Dark," a weird thing happened. Men started singing. "You can't start a fire, You can't start a fire without a spark," they bellowed. "This gun's for hire, even if we're just dancing in the dark." A bunch of guys, pumping their arms in the air, began to chant: "This gun's for hire. This gun's for hire." It was sad, and desperate, and kind of thrilling.

Lonely men do stupid things. Springsteen gave us permission to do them.

The first time I heard Springsteen I was working on a factory bottling line, packing industrial strength mayonnaise in downtown Los Angeles. The song was "Born to Run." I didn't like it. "Wrap your legs round these velvet rims and strap your hands cross my engines." Give me a break. It was an old high school compatriot who turned me around, forcing me to listen to the song again, headphones tight against my head, lyric-sheet open on my lap. "Baby this town rips the bones from your back, it's a death trap, a suicide rap, Got to get out while we're young . . ."

From then on, Springsteen's anthems of desperation and longing were the soundtrack of my own unsteady move from adolescence to adulthood. When I left L.A. permanently, at the age of 21, I played "Thunder Road," loud, on the car stereo, timing it so I crossed the county line just as Springsteen sang the words, "It's a town full of losers and I'm pulling out of here to win."

Over the years, Springsteen calmed down, got married, divorced, and remarried. He had kids. His music evolved to reflect his tentatively advancing maturity--and we all grew right along with him.

SO WITH Amber's sweet insistence--and her money, which I swear I'll pay back--I got up early the next morning and went to stand in the ticket line, with about a hundred other guys, all looking a little sheepish to be there.

I was surprised to see my friend Todd--who once owned every Springsteen bootleg there was--standing a few places a head of me.

Todd shrugged. "I thought I was past this whole concert-going thing," he said, "but . . ." I understood. This was no mere concert anymore. It had become a Robert Bly thing, a brotherhood of men uniting to honor their own path to adulthood.

"Now all we have to do is get tickets, " Todd added, as the doors swung open.

Ten minutes later, nearly every seat was sold out.

By the time we reached the counter, all that was available were seats back of the stage. Bruce wouldn't even be facing us.

"I don't know about you," I said to Todd. "I think I just need to be there." So that was that. Todd and I will be driving in together--and we'll take our kids, the next generation of Bruce fans. I really don't mind at all that I'll be forced to watch the show from behind the stage--at least we'll be there. And after all, it's a view of Bruce I'm very familiar with.

[ Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Bruce's butt: Bruce Springsteen--this gun's for hire.

From the October 21-27, 1999 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.