![[MetroActive Books]](/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | North Bay | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

New Tales

Armistead Maupin puts his own life at the center of 'The Night Listener'

By Gina Arnold

WHEN PEOPLE the world over picture the city of San Francisco, they think of many things: the Golden Gate Bridge, Alcatraz, Victorian houses, earthquakes. Then they people this pretty portrait with a bunch of kooks--drunks, hippies, gays, and liberals. And who can say they're wrong?

It's traditional. As far back as 1873, Jules Verne, in a passage in Around the World in Eighty Days, referred to it as "a legendary city of bandits, assassins, and arsonists, who had flocked to the city in search of gold." Jack London took over duties as chief chronicler of its vices at the turn of the century, while in the '40s and '50s, Herb Caen and Jack Kerouac helped turn the place into a hothouse of eccentricity.

Then came the '70s, and San Francisco's already wacky reputation turned decidedly pink. It was then that the Castro District's role as a haven for homosexuals became widely visible--thanks mostly to Armistead Maupin's Tales of the City, a daily serial that began appearing in the San Francisco Chronicle circa 1976. Any thought city residents might have had of escaping their legacy as a city of fruits and nuts came to an end.

Indeed, it's hard to exaggerate the effect Maupin's tales have had on San Francisco's public relations. His eight books have achieved that rarest of statures--world acclaim--and have remained in print for the past two decades. Three movies have been made of the series, with the result that Maupin's point of view--witty and trenchant and unabashedly sentimental--has come to color even the city's perception of itself.

Now Maupin has a new book out, The Night Listener--his first in eight years. The book introduces a new set of characters, but through them it continues to chronicle the City by the Bay as it grapples with new problems.The Night Listener reads like a memoir, and it certainly must be in parts, but it is also--like Tales before it--a real page turner, a perfectly paced mystery of sorts, permeated by Maupin's patented light touch.

He is, as he himself explains, "kind of like a comedian who can't use all his best material for fear of losing the audience." That's why reading aloud, on his many book tours, is one of his favorite things.

"Bliss," Maupin calls it, speaking from home just before departing on a book tour of England. (The author makes an appearance in Sebastopol on Saturday, Oct. 21, at an event benefiting Face to Face/Sonoma County AIDS Network.)

The city has undergone some changes in the years since Tales characters had freewheeling sex in gay bars and paid minuscule rents for fabulous apartments in the Marina. But Maupin's light, dry authorial voice remains the same.

That voice is gentle, courtly, and still touched with the Southern accent. Maupin grew up in Raleigh, N.C,, where his patrician (and very right-wing) father rubbed elbows with the local gentry. After a stint in Vietnam and a job as a TV reporter at a station managed by none other than Jesse Helms, Maupin moved to San Francisco. There he began writing the soon-to-be smash serial that celebrated (among other things) the free and easy gay lifestyle of the Castro District.

Tales chronicled the lives of a group of twenty-something characters on the north side of the city. The protagonist of The Night Listener, however, lives where Maupin does, in a western neighborhood called Woodside that abuts Twin Peaks.

The character, whose name is Gabriel Noone, is a 54-year-old gay man who grew up in the south. He did a stint in Vietnam, worked in TV journalism, and made his name in the '70s with a serial that celebrated gay life--albeit one that appeared on radio, rather than the newspaper. "I am," says Noone at the start of the book, " a fabulist by trade. . . . I've spent years looting my life for fiction."

The sentence inspires one obvious question: Is Gabriel Noone a thinly veiled Armistead Maupin, and if so, how much loot is in here?

"Well, I'm just not going to tell you," Maupin says. "No, I'm not trying to be coy, but my best material has always arisen from my reactions to actual experiences. On the other hand, I like to manipulate the circumstances and characters to make sense of them: real life is haphazard and tedious and often contradictory. But you step into really uncertain territory when you start trying to unravel the two things. You'll forgive me if I don't tell you quite how I do it.

"I'll say this much," he adds, referring to several plot points in the book. "I did break up with my partner four years ago, I do have an aristocratic Southern past and an 85-year-old father who still practices law and hobnobs with Jesse Helms."

So what part of Night Listener is fiction? "I do make some things up out of whole cloth," he adds. "I just spoke to my sister, who runs a bed and breakfast in New Zealand, and she'd just spent an hour on the phone reassuring my brother that I hadn't had sex in the cab of a truck in a snowstorm."

He laughs delightedly. "Of course, in many ways I wish I had!"

Another way he differs from Noone, he adds, is that "I am considerably more confident about my writing abilities than Gabriel is. But confidence isn't an interesting thing to explore."

Noone, who suffers from writer's block in the novel, feels, "as if I'd broken into the Temple of Literature through some unlocked basement window."

Maupin denies feeling that way--although one can't help but wonder if he has suffered from the malady in question, since The Night Listener is Maupin's first book in eight years.

"I'm not a compulsive worker," he says with an audible shrug. "Also, I like to have a long period of letting my life fill up so I can tap into it for ideas."

THE NIGHT LISTENER is an updating of the San Francisco zeitgeist--although the two main things that dominate the city's life right now--i.e., the profusion of dotcom businesses and the soaring price of real estate--are not mentioned herein.

Instead, the novel concerns the effect of AIDS, not just on those who've contracted it, but on those who haven't. Noone's live-in lover has had AIDS for years, but protease inhibitors have eradicated the virus from his body, a circumstance that alters each man's attitude toward the other, their relationship, and even toward life itself.

Just before Maupin finished the book, his--'whatdoyoucall it?" wonders Maupin aloud, "former significant other? business partner? friend? ex-lover?"--Terry Anderson came up with the idea of marketing The Night Listener online, as the first spoken word serial available on the web via streaming audio.

In September, each chapter, read aloud by Maupin, became available for direct downloading on Salon.com. Was the author embarrassed to read the sex scenes aloud? I ask.

Maupin roars with laughter again. "In a single word: YES," he shouts. "I kept wondering if the engineer could see me blushing behind the panel."

"But then, I've been afflicted by a perennial mild embarrassment my entire life. Sometimes," he adds, sighing, "I think I've deliberately put myself into situations to get past that--because I really believe we should be proud of who we are and what we do. If we aren't, we shouldn't be doing them."

[ North Bay | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

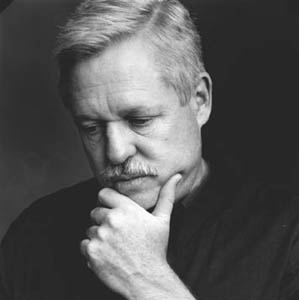

Photograph by Michael Amsler

From the October 19-25, 2000 issue of the Northern California Bohemian.