![[MetroActive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

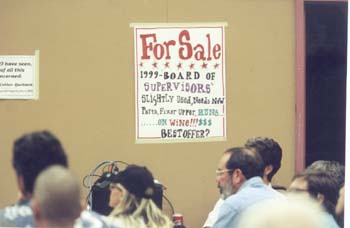

Sign of the times: Supervisor Mike Reilly sat in front of a protest sign at a recent forum called by activists to oppose encroaching vineyards.

Feeling the Crush

New vineyard-planting ordinance--is it a smart compromise or a sellout?

by Yosha Bourgea

A CONTROVERSIAL new erosion-control ordinance that regulates the planting of vineyards on sloped land has been reworded once again by the Sonoma County Board of Supervisors, but some environmental activists in the community claim that the ordinance still gives far too much leeway to local grape growers.

A much-anticipated public hearing, scheduled for Tuesday, Oct. 12, will provide a forum for citizens to express their concerns to the board on what has become one of the most emotionally charged issues in local politics: the impact of the wine industry on Sonoma County.

The Vineyard Development Ordinance, formerly known as the Vineyard Planting and Replanting Ordinance, grew out of an agreement reached between environmentalists and grape growers after one and a half years of intense negotiation. It was designed to establish riparian setbacksÑor minimum distances from the edge of streams, creeks and riversÑto prevent soil from muddying waterways and degrading fish habitats during winter storms.

The new revisions on the heels of two recent meetings at which hundreds of west county activists and residents gathered to discuss ways to curtail the effects of vineyard developments, including increased pesticide use, damage to native oak forests, the reduction of apple orchards and other farmlands, and the depletion of local aquifers.

The original ordinance, adopted June 15, included references to standards for erosion and sedimentation control, but didn't specify them. At the time, the board planned to have the county agriculture department develop and adopt those standards separately later in the summer. The ordinance was supposed to go into effect on Oct. 1.

But as that date grew closer, it became clear that the standards would not be in place by the deadline. Sonoma County Conservation Action president Mark Green, who was involved in the negotiation process, says that red tape and inexperience were partly to blame. "Government sometimes takes a while to do things," Green says.

"I will say that I'm disappointed, but I understand that it's a new program for the agricultural office. They need to find a staffer to do this job, and that person has not been hired yet."

On Sept. 21, the board, led by Supervisor Mike Reilly, voted to postpone the ordinance again, this time until Dec. 2. In the interim, a moratorium has been placed on new vineyard development with the exception of Level I vineyards--those planted on land with a predevelopment average slope of less than 10 percent (for erodible soils) or less than 15 percent (for non-erodible soils), though local activists have claimed that there is a rash of planting on steeper slopes in an effort to beat the deadlines.

"Functionally, the odds are good that [growers] won't plant anyway, because it could rain any day now," Green says. "Water Control and Fish & Game fines could be considerable if [the soil from] vineyards ends up in creeks."

Photograph by Michael Amsler

BUT the ordinance continues to draw fire from environmentalists who contend that its wording is biased in favor of the wine industry. Sebastopol activist Ann Maurice says that a loophole in the ordinance allows growers to tweak the average slope percentage in order to qualify their vineyards as Level I.

"The new ordinance is more obscene than the other," Maurice says. "This thing is so preposterous you want to just tell them to stick it."

In addition, Maurice says, the ordinance puts too much power in the hands of the county agricultural commissioner, a position held by John Westoby. Under the ordinance, growers are required to notify the commissioner in writing before they begin work on a site, so that he can determine whether the vineyard qualifies as Level I. But if the commissioner has not made that determination within 30 days, the vineyard is automatically classified as Level I and the grower is free to develop the site.

As Maurice points out, the commissioner is not legally obligated to make an official determination. If a grower's notice sits on his desk for 30 days, for whatever reason, the vineyard is approved by default. What makes this especially repugnant, she says, is that the ordinance makes all the commissioner's decisions final, and not subject to appeal.

"We want to protect the ag commissioner from having to take bribes," Maurice says with a blunt laugh.

Reilly, who has worked closely on the shaping of the ordinance, says that the intent of the 30-day limit was not to foster bribery or cronyism, but to protect growers from having to wait indefinitely for government approval. Like any crop, wine grapes are time-sensitive, and Reilly says growers wanted assurance that there would be action within a reasonable time.

"I'm going to ask for the ag commissioner to report back to the board if he can't make a determination," Reilly says. "If he doesn't act within the time frame, that needs to be public knowledge. If there's a pattern of underevaluation, it can be addressed."

Of greater concern, Reilly says, is the wording that classifies any replanting as Level I. "Replanting can mean tearing out 100 percent of [an existing] vineyard," he says. "If the purpose [of the ordinance] is erosion control, replantings could pose as serious a threat as new plantings."

ALTHOUGH environmental activists are less than satisfied with the provisions of the ordinance, many regard it as a two-steps-forward, one-step-back situation.

"This is an incremental gain," says Friends of the Russian River representative Joan Vilms, also a member of the committee that negotiated with growers to create the original ordinance. "It puts something on the books for the first time."

The riparian setbacks and slope limitations may be insufficient, she says, but they're better than nothing.

Meanwhile, the wine industry continues to thrive. As demand for Sonoma County wines increases, more and more farmers are giving up less profitable crops to take advantage of soaring grape prices. And industry giant Kendall-Jackson's recent purchase of a 500-acre dairy ranch on the Marin/Sonoma border --once considered unsuitable for grapes--highlights the aggressive expansion of vintners into undeveloped areas of the county--and the potential for new impacts on a marginal industry that may not be able to withstand the onslaught of vineyards.

"This area has been changed more in five years than it has in the last 100," local activist Kurt Erickson says. "The postcards will soon be out of date."

[ Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

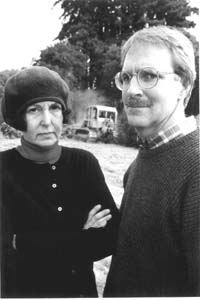

Photograph by Michael Amsler

There goes the neighborhood: In preparation for a new Sebastopol vineyard, a bulldozer chews up land adjacent to the home of Lori Silver and Huck Hensley, who say such winery development is leading to environmental degradation.

There goes the neighborhood: In preparation for a new Sebastopol vineyard, a bulldozer chews up land adjacent to the home of Lori Silver and Huck Hensley, who say such winery development is leading to environmental degradation.

From the October 7-13, 1999 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.