![[Metroactive Movies]](/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | Show Times | North Bay | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Kids Today

Avant-garde sheen can't hide exploitative heart of 'Bully'

By Richard von Busack

IF LARRY CLARK had only been a little faster, he might have gotten away with it. Clark's new film, Bully, repeats the bid for art-house fame he achieved in 1995 with Kids. But Clark won't be so lucky this time.

Bully is based on the true-life murder, in 1993, of Bobby Kent in a Florida suburb. The crime was novelized in the book of the same title by Jim Schutze of the Houston Chronicle. No one would call the Kent case a thrill killing, because the participants (seven of whom were eventually imprisoned) didn't derive much pleasure from it.

The victim was a would-be thug, a steroid user, and a fancier of that bully-boy urban music that sounds like pit bulls singing in chorus. The ring leader of the killing, Marty Puccio, claimed that Kent had been tormenting him since he was a child, though others noted the two seemed close enough to be lovers.

On the whole, scriptwriters David McKenna and Roger Pulis followed Schutze's account closely. However, Schutze's book didn't have a single attractive character, so the makers of Bully changed two of the principals into tender lovers.

Lisa Connelly, a pudge in real life, is played by the svelte Rachel Miner as a dreamy girl who hopes to have Marty's child (though the real Lisa panhandled to get money for an abortion). Marty is her sensitive lover, played by Brad Renfro in the best achingly post-James Dean style, though according to Schutze, Marty sometimes slugged Lisa and called her a fat bitch.

The victim, Bobby, is white, though in real life he was of Iranian parentage. Bobby is played by Nick Stahl, less a bruiser than a twerp. In one typical scene, Stahl lets the mirror have it with a mouthful of spit. Mistreating a mirror is the hallmark of the overcompensating actor.

The film starts out with two girls at the mall. Lisa and her promiscuous pal Ali (Bijou Phillips) pick up Marty and Bobby, the couples park, and Ali presents her barely covered ass to the camera as she buries her head in Bobby's lap. It's effortless coupling, a teenage dream of the way things work. It's not a bad way to open a movie. But Clark seeks more tension, more argument, and the film sputters.

Bully unfolds in terms of an old drive-in movie about juvenile delinquents: it's a protest against toxic culture. The video games, the porn, and that bitch-bitch-bitch music turned this gang crazy, just as juvenile delinquents of yore were inflamed to crime by Fats Domino.

Updating the old so-young-so-bad-so-what theme could have provided some cheap thrills. But that enjoyment is impeded by Clark's pretense at avant-garde filmmaking--his floppy camera work, his lunch-disrupting merry-go-round cam.

There's something cheap and exploitative in Larry Clark, and I urge him to let it out: his seriousness just invites derision. At its best Bully is dirty fun. A few may consider this flick profound--which it profoundly isn't.

[ North Bay | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

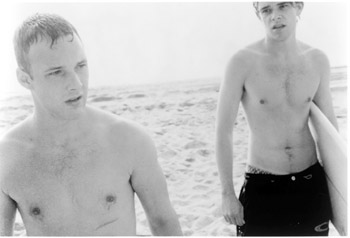

Bad seeds: Brad Renfro and Nick Stahl play wicked teens in 'Bully.'

'Bully' opens Friday, Oct.5, at Rialto Cinemas Lakeside, 551 Summerfield Road, Santa Rosa. For details, see Movie Times, page 31, or call 707/525-4840.

From the October 4-10, 2001 issue of the Northern California Bohemian.