![[MetroActive Dining]](/gifs/dining468.gif)

[ Dining Index | Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Mind Food

Agustín Gaytán puts a new twist on old Mexican favorites

By Marina Wolf

SOME PEOPLE don't remember anything from their childhoods. Agustín Gaytán remembers everything, and most of it revolves around food. Tamale-making parties for holidays. Moles, the complex sauces ground and mixed by hand in a stone motate. Giant sweet fritters called bu--elos, made in mountains for Christmas and Día de los Muertos; Gaytán remembers a circle of family and friends sitting around and stretching balls of the soft, elastic dough over their knees until the disks were enormous, and then throwing them into a copper vat filled with boiling oil.

Gaytán does his best to pass along the traditions to his classes at Ramekins Sonoma Valley Culinary School, where he is essentially the Mexican expert-in-residence.

Nowadays the dark-eyed, energetic young chef is playing with more exotic ingredients, making things like pesto and smoked chicken tamales. His mother might not recognize what Gaytán calls tamales nuevo, but to Gaytán, they are simply the newest evolution of an age-old cuisine that has survived--and thrived on--countless infusions of foreign influence.

"The cookbooks in Mexico from the 1800s reflect an amazing combination of cultures," he says, leaning forward excitedly from his perch on a friend's plush sofa in Petaluma. "It was already basically fusion cookery: European preparations, with lots of chiles."

Gaytán's earlier food experiences were somewhat less experimental. San Miguel de Allende, the historic central Mexican city where Gaytán was born and raised, has a large American community. But his mother's foods were strictly Mexican, so the few times he ate American food at American friends' homes, Gaytán was a bit taken aback: "The food suddenly wasn't as exciting and vibrant."

And when he moved north to Texas in 1986, at age 24, he was even more confused by the food at the restaurant where he found his first American job, as a busboy. On the menu it was called "home cooking," but with mostly black staff, it was basically soul food. "I didn't know the difference," Gaytán says with a laugh. "I thought it was just American food."

Eventually Gaytán would learn the sad truth, but for the moment he was enchanted by the abundance and flavorfulness of the food. Eventually he became the baker there, making the restaurant's breads and pies "all from scratcchh," he says, savoring the word. Pies he had met before, as pays in Spanish, but never the varieties that he was called on to make here: peach, apricot, apple, and the cream pie, in chocolate, coconut, and peanut butter.

IN SPITE OF THIS exciting introduction to the American food industry, Gaytán was initially unswayed: he wanted to go to college and study anthropology. But when he moved to California some 10 years ago, an American acquaintance from San Miguel invited him to form a catering and restaurant partnership called Dos Burros.

It was at the Oakland eatery in 1990 that Gaytán found his second calling: teaching. What began as informal classes grew to include workshops at cooking schools all over California, Texas, and Colorado, and even in New England. And though Mexican food had become a familiar taste to the American palate by then, Gaytán found that many people still needed pointers.

"Most people here think Mexican food is all No. 4 combination: refried beans and rice, chile relleno, and enchilada on the side," he says with an expressive twitch at the corner of a gentle smile. "But even among the people who are more educated about food, there is still a resistance that clearly comes from ignorance. People are not willing to accept that Mexican food is as well developed and as refined as any other cuisine."

Some of this reluctance is based on run-of-the-mill racism, something that Gaytán has often experienced in the culinary world. "I always have to work twice as hard to get accepted as a teacher at different cooking schools," he says. "If I was a white man, I would be accepted more easily, even though I am teaching my own country's cuisine."

But he is willing to excuse some of the prejudice as basic culinary ignorance. Gaytán's students often are simply unaware of what salsas go well with what meats, or what cheeses should be added to what dishes for the most authentic effect. This is no simple thing, for "Mexican" food is indeed as diverse as American regional foods, if not more so. Even for Gaytán, the regional variations were strange and fascinating, especially at the beginning. "Moving from region to region is like going from country to country," he says.

HIS NATIVE STATE of Guanajuato boasts a proud assortment of chiles, but Gaytán found a selection to rival it in Oaxaca. There he also found seafood being used in ways that Americans might consider strange, if not downright extravagant. Oysters and clams make regular appearances in tamales. There was even a tamal made with a whole, unshelled lobster, surrounded by masa dough that would soak up the juices after the tamal had been baked and the lobster cracked open.

Elsewhere Gaytán found regions that--gasp!--just don't use chiles that much. In Yucatán, for example, the favored flavor base is recado, a paste made of onion, garlic, and spices. Recado rojo (red recado) gets its distinctive color from achiote, or annatto seed, while recado de bistec is made olive-green with cumin, oregano, and chiles, and recado de negro contains ingredients that have been deliberately and deliciously burnt black.

But before they get to recado and lobster tamales, some folks just have to learn where to shop. To meet this need, Gaytán has created a cook's tour of San Francisco's Mission District, in which he leads groups of students, senior citizens, or just plain curious gourmets through the produce markets, panaderias, and carnicerias of that predominately Latin American neighborhood. He realizes that the district, like many San Francisco neighborhoods, is threatened by gentrification, and he sees his popular tours as a way of asserting identity.

"I want to contribute to the stability of the Mission District as a Hispanic community," says Gaytán. "And food, you know, is very culturally binding."

Chiles Rellenos de Pescado en Mil Hojas

6 poblano chiles

1. Roast chiles over a direct gas flame at medium-high heat or under a broiler. Turn chiles over from time to time until skins are blistered, about 6-7 minutes. Place chiles inside a plastic bag or a towel and allow to steam for 10-15 minutes. Peel chiles, split them, remove seeds, and place in nonmetal bowl.

2. Cut fish into 6 equal portions. Sprinkle all pieces with the salt, pepper, and lime juice. Marinate 15 minutes in a nonmetal bowl.

3. Heat oil in a 10-inch skillet and sauté onion and garlic for about 4 minutes. Add tomatoes, olives, capers, chiles, oregano, bay leaf, and salt. Cook for 15 minutes over medium heat. Cool to room temp-erature. Preheat oven to 400°.

4. Stuff each chile with fish (cut each portion of fish into smaller pieces to fit inside chiles).

5. Roll out each piece of pastry large enough to completely wrap around each chile according to size.

6. Wrap each chile and seal edges with water. Place chiles seam side down on greased baking sheet. Brush top of each chile with beaten egg and bake for about 20 minutes until golden brown. Serve hot or at room temperature with remaining tomato sauce. Serves 6.

[ Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

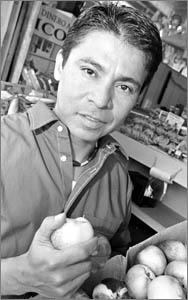

Shock of the new: Chef and educator Agustín Gaytán shares his knowledge of nuevo Mexican cooking at Ramekins Sonoma Valley Culinary School.

Shock of the new: Chef and educator Agustín Gaytán shares his knowledge of nuevo Mexican cooking at Ramekins Sonoma Valley Culinary School.

(Chiles stuffed with white fish, tomatoes, and olives, then baked wrapped in puff pastry)

1 1/2 lbs. red snapper filet

1 tsp. sea salt, approximately

1/2 tsp. freshly ground black pepper

3 tbls. fresh lime juice

1/4 cup extra-virgin olive oil

2 lbs. ripe tomatoes, grilled, peeled, and coarsely chopped

1 medium onion, coarsely chopped

3 large cloves garlic, peeled and sliced

10 large green olives, pitted and cut in half

3 tbls. large capers

2 pickled jalapeño chiles, cut into small strips

1/4 tsp. oregano

1 large bay leaf

1/2 tsp. sea salt (or to taste)

10 sheets puff pastry, store-bought, ready-made, cut to size (5x4 inches)

1 egg, lightly beaten

From the September 28-October 4, 2000 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.