![[MetroActive Arts]](/gifs/art468.gif)

[ Arts Index | Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Last Call

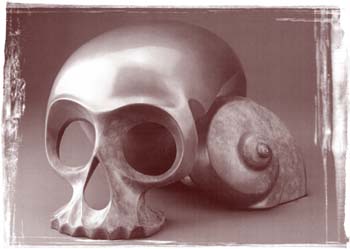

Bone deep: Sculptor Ronald Garrigues' Dr. Frankenloner is part of the upcoming Día de los Muertos exhibit at the Sonoma Museum of Visual Art.

Death is the life of the party at the new SMOVA art exhibit

By Paula Harris

"WE MUST remember them," say the Zapotec elders about the Dead. "They want us, they love us. See how that flame danced high before it died? It is the Dead, letting us know we are not to forget them."

Benjamín Lopez, 56, an artist and seasonal vineyard worker, holds these ideas dear as he crouches forward to drape and smooth a snowy linen cloth across an expansive altar, which he will soon decorate with small angels, flickering candles, and garlands of fresh white flowers.

Lopez, who migrated to the United States in 1977 and now resides in Healdsburg, learned the art of altar-making and decorating as a teenager growing up in a tiny village in the Mexican state of Oaxaca.

"When I was 16 years old, my godfather, who was a decorator in my village, asked me to be his assistant without compensation just to learn the trade," recalls the shy artist in Spanish, communicating with the assistance of a translator.

Using colorful tissue paper, card stock, foam boards, fabrics, natural woods, and fresh or dried flowers, Lopez created nativity scenes, floats for parades, funeral altars, and decorations for weddings and birthday parties in his village.

"Each occasion was different, a different fiesta," he explains. "I really enjoyed making different representations of biblical and cultural themes."

Now widely recognized as an artist, Lopez created an elaborate, multitiered altar for the Oakland Museum of Art last year in memory of the more than 180 people who died crossing the U.S.-Mexican border in 1998.

During the annual Day of the Dead festival, embraced by many Latin American cultures, death's morbid side is buried under a joyous celebration that includes feasting, frivolity, and fond remembrances.

According to ancient tradition dating back to the Aztecs, who believed death was merely a portal to another existence, departed souls journey back from the netherworld each year to visit loved ones. Hailing from Heaven, Hell, and Purgatory, the Dead descend upon their families, and for two days--Nov. 1 and 2--everyone rejoices together.

"In Mexico's indigenous cultures, we firmly believe that our relatives and friends who have passed away come back to earth in early November," explains Lopez. "The altars I make are an expression of art, an extension of me. . . .When I make altars now I have great memories of my youth and my village."

The altars are often elaborately embellished with an array of earthly delights in the hope of luring departed spirits. Ofrendas (offerings) may include bottles of beer or tequila; platters of rice, beans, chicken, or meat in mole sauce; candied pumpkin or sweet potatoes; and the traditional sweet loaves. It is widely known that the Dead love sugar. The offering may also include a pack of cigarettes for the after-dinner enjoyment of former smokers, or a selection of toys and extra sweets for deceased children.

Lopez's altar for the children will be one of three community altars featured at the SMOVA Day of the Dead bilingual exhibition titled Homenaje a Nuestros Antepasados (A Tribute to Our Ancestors). Other altars will pay tribute to the ancestors of this community and to those who have died in the struggle for equality. The SMOVA presentation is a collaboration between local schoolchildren, Latino artists, and community groups.

"The exhibition becomes so much richer with all this input rather than if one person just sits down and tries to figure out what we'd show," says museum director Gay Shelton.

THE EXHIBITION WILL also feature a 10-foot octagonal sand painting sprinkled with colorful pigment created by Zapotec artists from Oaxaca as an homage to their deceased teacher, bronze skull sculptures from the Endangered Species series by Mill Valley artist Ronald Garrigues, a silk-screening demonstration by Calixto Robles of Oaxaca, and Saturday afternoon puppet shows.

The Dead will be full of life--frolicking, in fact. Shelton says original skeleton puppets (such as a shopkeeper with her rib cage exposed above her full skirt, and a skeleton mama and her bony baby) will clatter about poking fun at death. Art by local schoolchildren will include Barbie dolls painted like skeletons and ceramic bones dangling from the ceiling.

Clearly, certain Latino cultures have no qualms about getting up close and snugly with the Grim Reaper. In fact, the inevitability of death is accepted rather than feared.

"It's really interesting--the whole tradition is about making friends with death," says Shelton, adding that, during Day of the Dead, Latino children often crunch down on candy skulls inscribed with their own names.

"You imagine yourself as a skull," she says with a laugh. "It's a friendly approach to death--it's nothing about fear and denial like we experience in our culture."

[ Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

CANDIDO MORALES

CANDIDO MORALES

His latest work, Homenaje a los Angelitos (Tribute to the Little Angels), a community altar dedicated to children and infants who have passed away, will be featured in the Sonoma Museum of Visual Art's upcoming Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead) exhibition.

The Homenaje a Nuestros Antepasados exhibit opens Thursday, Sept. 16, and continues through Nov. 2 at the SMOVA, Luther Burbank Center, 50 Mark West Springs Road. Puppet shows will take place each Saturday at 3 p.m. On Oct. 3, Calixto Robles demonstrates the silk-screening process. On Oct. 30, the public is invited to contribute to a community altar. Regular exhibit hours are Wednesdays and Fridays, 1 to 4 p.m., Thursdays, 1 to 8 p.m., and Saturdays and Sundays, 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. Admission is $2/general; free for those under 16. For details, call 527-0297.

From the September 9-15, 1999 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.