![[MetroActive Features]](/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Spanish Moon

A week in the

redwood wilds

at flamenco camp

By Paula Harris

Photos by Michael Amsler

MELLOW morning sunlight slants gently through the soaring Mendocino redwoods while smoke billows up from the old stone fireplace in the nearby lodge, perfuming the air. A sleepy-faced guitarist in disheveled sweats slumps outside under a tree, alternately sipping from his steaming mug of coffee and lazily strumming soft, sweet chords. Tranquility.

But not for long.

A deafening maniacal pounding abruptly shatters the peace. It thunders through the forest like a vicious barrage of gunfire, sending lizards darting back under rocks and small birds scattering through the sky.

If the din belonged to the world of nature, it would most resemble an army of destructive woodpeckers on meth. It's just the advanced flamenco dance class practicing footwork exercises on the wooden floor in the main hall down the hillside.

And so begins another day at flamenco camp in the redwoods.

How did we get to this point? One hundred and three flamenco enthusiasts (mostly men and women from all over the United States) have gathered to commune with nature while living like a band of grubby vagabonds in the wilds of this immense forest in Mendocino County.

The Flamenco in the Redwoods weeklong workshop-cum-summer camp is the brainchild of the internationally acclaimed local flamenco dancer known simply as La Tania (who, when not touring with her own company, resides in Willits) and her troupe's general manager, Steve Marston.

For around a hundred bucks a day, participants get a cabin, all the food they can eat, and four hours of daily instruction. The workshop has an added draw: La Tania contracts with rising flamenco stars from Spain to teach the courses. Immediately following the workshop, the instructors form a troupe and go on tour.

Now in its second year, the unusual workshop, held in August, has picked up pace, attracting flamenco singers, dancers, and percussionists of all levels from various locales, including New York, Chicago, Atlanta, Phoenix,

Santa Fe, Seattle, and Fort Worth.

"The concept is to have everyone together interacting between the three flamenco disciplines," explains Marston, who acts as camp director. "And there's no distraction here--people can concentrate."

The camp is held at the 720-acre Mendocino Woodlands Outdoor Center, a national historical landmark. The secluded camp in the heart of a redwood forest was one of Franklin D. Roosevelt's "New Deal" camps conceived as "training grounds" to acquaint the underprivileged with the joys of the woods.

Forty-six other camps were built during the Depression era as part of the New Deal. One, Camp David in Maryland, became the presidential private retreat. Marston tells me the Mendocino Woodlands is the only camp of the 46 original parks still being used for its original purpose--to live in the wilderness.

This bohemian lifestyle is what draws many flamenco fanatics.

"The whole campo thing is here," explains Marston, "the whole gypsy scene of being apart from mainstream society. You think of gypsy scenes around a campfire outside of town, and this re-creates a bit of that same ambiance. We wanted students to be immersed in the whole environment, spend time together, and become comfortable."

But how comfortable can one be housed in a primitive log cabin without electricity or water and dealing with, uh, the wonders of nature?

"The destination is a shock to some people," admits Marston. "But on the whole, people get used to it. We do what we can to make it comfortable. But I can't rid of the bats that plague some cabins and fly down the chimney during the night. That can be unnerving, but at least the bats eat the mosquitoes."

Hearing this does little to reassure me, a city gal who grew up happily basking in the harsh neon lights of central London. I take flamenco dance classes, all right, but I've never been camping in my life. Sure, this isn't on a par with, say, trekking up Mount Everest or participating in Survivor.

But still, I wonder what's in store. . . .

Day 1

A guitarist friend is driving me and another workshop participant to the camp. The car is heavily laden with sleeping bags, battery lanterns, a guitar, flouncy flamenco skirts, and well-worn dance shoes. We wind our way up curving, precarious roads. The trees grow thicker at every turn, eventually leading to the final destination.

Marston is on hand, grasping a clipboard and looking very polished for such rural surroundings in a crisp, pressed shirt.

He directs us to our crude dwellings: rustic secluded cabins of unfinished redwood with no locks on the doors, a craggy stone fireplace streaked in the front with black soot, a minuscule closet without hangers, four skinny cots, and a small veranda. That's it. The trees are clustered so densely they block any light from seeping inside our new abode. It's not even dark out, but we need flashlights to unpack.

We also need the flashlights to find our way along the pathways to the main lodge for the welcoming dinner. The trails are treacherous: steep and fraught with barely hidden stumps, roots, and rocks, with a sheer drop on one side. We hitch up our long ruffled dance skirts and concentrate on our weak beams of light on the powdery ground ahead.

Later, when we turn in, we're too exhausted to worry about bats flying down the chimney. I wake up a few hours later because something is in the corner chomping on a knotted trash bag in the dark. The next morning the wood floor is littered with Kleenex fragments like white snow.

Day 2

Our guitarist friend who gave us the ride up here already has quit flamenco camp. He's walked out before the end of his first lesson this morning, claiming the music being covered is "too modern" and doesn't interest him.

"You'll have to find your own way back," he tells us determinedly as he leaves.

We wonder whether it was really the music (some of which does sound untraditional) or the conditions that drove him out. We recall he'd mentioned that, being tall, he's used to a king-size bed and that he'd painfully tumbled out of his coffin-sized cot onto the floor last night.

The curriculum is intense. Dance is held in a large central lodge with an echoing, scarred wooden floor, exposed beams, and another oversized rough-stone fireplace. There's a row of mirrors on wheels along one wall, but one has broken in transit.

Singing class is held in a small, dark, and depressing cabin that's perfect for the wrenching music. Beverly, a normally perky San Francisco nurse, can't help but weep when she belts out the solea, a soul-bearing song about loneliness and exile. Her voice is deep and raspy-raw, falling and rising in sobering waves of emotion in the semi-darkness. The guitar cries along with her.

Day 3

Our advanced-class dance teacher, Elena Santonja from Madrid, who with her battered leather jacket and wild red hair looks like a rock star, is even more excitable than usual.

She stretches her slim flexible arms above her head forming a point with the palms--a sort of charade for what she's trying to convey, because she doesn't know the word in English. Eventually we understand the mime: she'd found a scorpion in her cabin last night.

"What did you do?" someone breathes. With a spell-weaving smile Santonja very slowly raises her right leg high above her knee in a dance pose, then smashes her metal-tipped purple-suede flamenco shoe down hard on the floor in two rapid ear-splitting stomps.

"I do it fuerte with all my soul," she explains. "¡Pero que miedo!"

Santonja is so enamored of the scorpion step that she includes it in our choreography.

Later on, a dance student is taking a shower in the bathhouse and notices a small black scorpion clambering up the green plastic shower curtain. It doesn't faze the woman, who simply unhooks the curtain, grabs it, and strides naked out into the woods to humanely shake the critter out.

Julia, a dancer from Alabama, tells us that when she unpacked from flamenco camp last year, she discovered she'd unwittingly transported a live scorpion to her home, air freight. "There it was in my suitcase," she drawls.

From now on I search the recesses of my sleeping bag with a flashlight each night and shake out my dance shoes each morning. My cabin-mates call me paranoid.

We don't find a scorpion inside the cabin, but suddenly about 30 large, plump black flies appear from nowhere (we're keeping the windows and door closed at all times). They darkly coat the inside of the window behind the cots like some biblical curse. Two days later they've vanished without a trace.

Day 4

José Anillo, the advanced-course singing teacher from Seville--dark-eyed, young, and stocky, with a spiky buzz cut--is in love with a redwood branch.

He's carefully carved it into a perfect thick white walking stick, and it's become his constant companion. He leans on it to trek up the hillside, wields it ominously in class, and aims it piercingly toward his heart whenever a student warbles offkey.

The beautiful, exotic La Tania is teaching us how to both smoothly and sharply slither our hips and how to rotate our wrists to make perfect curls with our fingertips in the intermediate technique class.

"Don't be afraid to move," she tells us, pausing to clip back her long black hair with a plastic comb. "We can do whatever we want. No one can see us in the woods."

We begin to routinely smell of sweat, wood smoke, and bug repellent. A fine dust from the dry earth powders everything--clothes, shoes, and skin. We no longer care. When not in dance class, we're exhausted but practice in small groups on small wooden platforms set up outside around camp for this purpose. We cluster together to see if, among us, we can recall the complex sequences of dance steps from repertory class.

All the strenuous exercise is wreaking havoc on our appetites. We're eating like starving toros, and the catered food is good and plentiful. From fresh abalone cooked in garlic (nabbed by a member of the group who's a diver), to Thai curries, to Spanish tortillas, and all sorts of homemade cakes and cookies, it's so good. The organizers' philosophy is that if they keep our bellies full, we'll forget the hard mattresses.

It seems to be working.

Tonight, though, two dance students are a couple of hours late for dinner. They got locked in their isolated cabin when the inside door knob came off in someone's hand. The most agile of the dancers eventually had to shimmy off the veranda and down the eight-foot drop to come back around and open the door from the front.

Amazingly, we're beginning to take such stories in our stride.

All the participants gather together at night to eat and talk, but also for impromptu flamenco song and dance in the cozy, rustic dining room. We're now kin, and we've definitely taken on a sort of tribal quality. Tonight all the men have painted the pinkie nail of their left hand with red polish, and all the women have daubed silver glitter onto their cheekbones.

"It would take a few more days until we become a family, but we're headed in that direction," says Marston. "We all eat and sleep the flamenco environment."

Each night we take our flashlights and trek down to the crackling fire pit and forest amphitheater where the organizers have rigged up a large stage with lights and sound system. Singers, dancers, guitarists, and drummers pass around bottles of tequila and jam ferociously into the night. The music extends way beyond flamenco, often incorporating rap, '70s disco-funk, blues, and African tribal rhythms.

We now go to sleep with those sounds reverberating through the forest, and awaken to the cacophony of a dozen guitars tuning up.

Day 5

Elena Santonja is standing outside instructing an afternoon palmas (hand-clapping) class. Various insects are dive bombing her: an enormous dragonfly, a buzzing band of mosquitoes, and a large, venomous-looking red-winged bug. She leaps gracefully up onto a tree stump, clapping her hands around her face, her eyes wide. "I don' wanna die in the forest!" she wails comically from her wooden pedestal. "I wanna go back to Madrid."

Meanwhile, we employ our newly learned rhythmic hand claps to kill mosquitoes in midair, reducing them to tiny bloody stains with legs on our palms. Still, the pests are feasting on us, even through thick dance tights and sweaters. The highly touted repellent lotion I've brought along does little to ward off the bloodsuckers.

Day 6

The mosquito bites on my ankles, shins, and knees are so painfully inflamed and swollen (some kind of allergic reaction) that the ferocious footwork is sending hot dagger stabs up my legs. I carry on regardless, feeling like that woman in Survivor, the one with the open sores, and feel surprised by actually enjoying the challenge.

We are working toward a performance later tonight.

But there again everything about flamenco is tough, frequently painful as well as joyous, and layered with emotion. As with living at the camp, you must overcome physical and mental challenges to succeed. "Flamenco is a calling," concludes dance and song student Helen, a retired librarian from Cotati. "It's much like a religion: you're compelled to delve into it, learn, gain, and connect with it."

We nod knowingly. An elusive

calling.

The art form is also attractive because it's a communal expression. "It's about community, too," says La Tania, "You don't see much of this nowadays; there are not many gatherings, not many big dinners. This becomes like a big family--you know each other, live together a whole week, jam together. Flamenco is not a type of dance to do by yourself--you need a singer and a guitarist. This way you live the whole thing the way it should be."

Day 7

Maybe it's just because we know we're about to head back to the comforts of home, but we're really beginning to appreciate the past week's experience--bugs and all.

Instructor and fellow city gal Santonja is enthusiastic about the experience. "It's amazing that people here come to a wood to learn flamenco--they have a lot of will to do it," she says. "It's an example for Spanish people who should organize something like this in Spain. To a degree, it has been uncomfortable, but in the end you forget the discomfort; you are free without pressure and can search for and find a channel to express yourself."

Susana, an arts sales rep from Aspen, Colo., says she was isolated and starved for flamenco but can go back fortified. "I had no idea how much I would learn," she says.

And Jan, a yoga teacher and mother of four from Occidental, calls the experience "a hermitage."

"I loved the lack of electricity, that we made fires. That there were no phones, no TVs," she explains. "I feel completely invaded by the electronic world--this was a return to stimulation and absorption made by ourselves."

"¡Olé!," we respond, scratching our bug bites. "¡Olé!"

[ Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

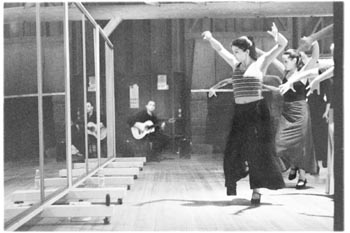

Class act: Instructor and workshop organizer La Tania leads students through the paces, a grueling regimen of dance techniques and routines conducted seven hours a day in the rustic redwood lodge deep in a Mendocino forest.

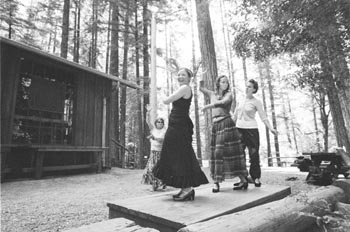

Outdoor cookin': Stacy Estrella, in the full-length black skirt, Martina Nutz, and Meadow Shere stage an impromptu table-top performance for a curious onlooker.

From the September 7-13, 2000 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.