![[Metroactive Dining]](/gifs/dining468.gif)

[ Dining Index | North Bay | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

Fictional Food

The way to a child's mind is through the stomach

By Gretchen Giles

On a single day, young Almanzo Wilder polishes off a sandwich of homemade bread and butter with sausages, eats two doughnuts, has an apple, four turnovers, a plate of baked beans, a serving of salt pork, a pile of mealy boiled potatoes with brown, ham gravy, more bread with butter, some mashed turnips, a helping of stewed pumpkin, spoonfuls of plum preserves, strawberry jam, and grape jelly, a few spiced watermelon-rind pickles, a piece of pumpkin pie, as much hot buttered popcorn as he can swallow, another apple, and a refreshing draught of cider. He longs for some fresh milk in which to douse his popcorn but doesn't wish to disturb the heavy cream that's rising atop the milk can, so consoles himself with yet another apple and drink of cider.

After chores the next morning, he tucks into a bowl of oatmeal with thick cream and maple sugar, lavishes himself upon fried potatoes, has as many golden buckwheat cakes with sausages and gravy and butter and maple syrup as he wants, selects among an enduring abundance of preserves and jams and jellies and homemade doughnuts, and ends his repast with "two big wedges" of spicy apple pie.

The boy is eight, that was breakfast, and we're only up to page 37.

Over the course of Farmer Boy, Laura Ingalls Wilder's biographical book about her husband's childhood, young Almanzo will enjoy chicken pot pie with the meat of three hens bubbling under the crust, spoon up wild strawberries with cream, have stuffed roasted goose for Christmas dinner, wait hungrily for the crisp, crackling roast pig to be sliced, watch his mother fry cornmeal-battered trout, and, as Mrs. Wilder describes it, simply "eat and eat and eat."

While there is character arc and a sturdy plot line to this seminal children's book, it also ably acts as an I Ching of childhood food fantasies. Throw a coin onto almost any page, and the characters are certain to be either cooking, eating, planting for later eating, feeding animals, sugaring sap, or sneaking doughnuts, warm cookies, and full round cakes of maple sugar into their pockets. Even the prize pumpkin that Almanzo raises for show is solely fed on fresh, warm milk intricately wicked up from bowl to vine with candle string. Add some schoolyard fisticuffs, break a colt, and that's the book.

Of course, Wilder hardly butters new ground by larding Farmer Boy handsomely with food references. Winnie the Pooh's obsession with honey is a legendary character trait; Robin Hood was known to dine only upon roasted venison; Pippi Longstocking regularly ate more than her weight; and readers of Maurice Sendak's Where the Wild Things Are have long associated mastication with affection, as when Max, the main character, is told by his parents that "we love you so much, we'll eat you up." Sendak also entertains directly from the Night Kitchen and extols the lovely, numeric pleasures of chicken soup with rice.

From book springs book--or at least product. Charlie and the Chocolate Factory launched its own enduring line of Wonka candy, just as Harry Potter produced an actual brand of Bertie Botts Every Flavor Beans, featuring tastes from mango to snot to root beer to vomit. The Thousand Acre Wood gang have at least two children's cookbooks detailing Winnie's gastronomic devotions, and Wilder's Little House on the Prairie series has several lavishly researched cookbooks based upon it.

Even the Care Bears have a sugary little tome--Beatrix Potter's characters too. (Remember the blackberries and cream Peter Rabbit eats to solace his adventures? Yum.) Roald Dahl's Revolting Recipes draws from his extensive oeuvre to describe, among other things, the process required to create the "Mosquitoes' toes and wampfish roes / Most delicately fried / (The only trouble is they disagree with my inside)" so lustily sung about by the centipede in James and the Giant Peach. While the centipede may boast of enjoying hot noodles made from poodles, toes 'n' roes actually fall to earth in the form of fried cod sandwiches rolled in sesame and poppy seeds, making poodle noodles sound all the better.

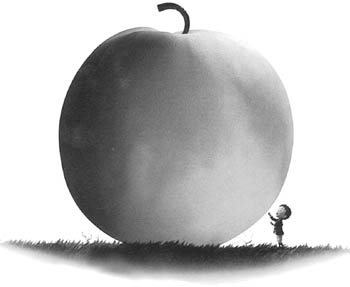

And speaking of James, how about that peach! Some scholars liken the role of food in children's literature to that of sex in adult reading. When James first approaches the massive fruit, so large that it rests upon the ground, he notices a hole in its soft skin and climbs in. Finding this to be a tunnel entrance, he crawls forward. Dahl writes that "the floor was soggy under his knees, the walls were wet and sticky, and peach juice was dripping from the ceiling. James opened his mouth and caught some of it on his tongue. It tasted delicious. . . . Every few seconds he paused and took a bite out of the wall. The peach flesh was sweet and juicy, and marvelously refreshing."

You needn't be a Freudian analyst in order to cop a wink-winknudge-nudge leer from the edible return-to-the-womb sensuality of this description. Yet its very innocent physicality endures; few of us who read James as children can eat a ripe peach today without reflecting sweetly on this boy's wild adventure in fruit.

Similarly, there is a wholesomely salacious abandon to the endless round of bubbling doughnuts and hot, spicy pie found in Farmer Boy, to the milk-chocolate river that finally seduces Augustus Gloop in Charlie, and to the wantonly-appearing platters that makes boarding school all the more appealing to fans of Harry Potter. Voldemort is a lot easier to battle if there are "roast beef, roast chicken, pork chops and lamb chops, sausages, bacon and steak, boiled potatoes, roast potatoes, fries, Yorkshire pudding, peas, carrots, gravy, ketchup, and, for some strange reason, peppermint humbugs" on the table, as there is at Harry's first Hogwarts repast. We have, alas, yet to meet a children's book hero other than Babar who adheres to a vegan diet.

So yeah, sure, right--food is to kids what sex is to adults, at least when we're reading. Perhaps. But how about food is safety, comfort, security, and stability to children as . . . it is, in fact, to adults? The superabundance, the outrageous portions and proportions described in these books all underscore the satiation of "enough." Enough love, enough comfort, enough warmth and shelter, and enough attention are all expressed in the serving of way more than enough food.

The Grapes of Wrath specter of Hooverville kids hungrily ringed around Mrs. Joad's empty stew pot, hoping to swipe a fingerful of sop from the pot's sides, rarely appears in children's literature. Brian Jacques, the English author of the Redwall series of fantastical juvenile lit, regularly features such fare in his tales as cakes made from arrowroot and pollen flours, chopped chestnuts, honeyed damsons, sugared violets, raspberries, and wild buttercup and blackberry creams finished with crystallized young maple leaves. The mice and moles that people his books feast regularly on such dainties while sipping rosehip-honey-strawberry nectar.

Visiting Sonoma on tour some years ago, Jacques declared that he began writing because he was tired of kids' books that had a muddle of antiheroic protagonists who occupied an unclear middle ground between right and wrong. There's good and there's bad, he explained to the children ringed rapt around him, and good always wins.

Particularly, it seems, when it's fictional and marvelously well-fed.

[ North Bay | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

From the August 29-September 4, 2002 issue of the North Bay Bohemian.