![[MetroActive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

![[MetroActive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Features Index | Sonoma County Independent | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Teens & the Law

Photo by Michael Amsler

Legal rights no minor issue

By Paula Harris

IT WAS A SUN-FILLED summer afternoon one recent Thursday as Amber Radich, 17, a Guerneville resident with a summer job at the Sebastopol Center for the Arts, sat in Ives Park quietly enjoying her lunch hour. Wearing work clothes and with her hair in pigtails, Radich had finished her sandwich and was about to bite into an apple when, she says, a local police officer riding a bicycle peddled up "out of nowhere" and began questioning her. The incident, she maintains, included the officer lying to and harassing her, and ultimately escalated into her arrest.

"He said my mother had sent him to check up on me. That wasn't true," she recalls. Radich says the officer asked what she was drinking--it was a Sunny Delight, a fruit juice drink--then saw she had a pack of cigarettes and began hassling her. "He was trying to find an excuse to bust me," claims Amber. "He then peddled away. I was pissed because I just got harassed, so I lit my last cigarette; then two friends came by and asked for a drag."

She says the police officer, who'd been circling the park, pulled up and asked her for identification. He then called for backup and two police cars arrived. They arrested Radich--who was by then crying--handcuffed her, put her in the back of the police car, and drove her to the Sebastopol Police Department on a charge of furnishing tobacco to a minor.

Zero tolerance for drugs. Cops on campus. Curfews. Tobacco and alcohol crackdowns. Gang task-force sweeps. These days, kids--and parents--are faced with an increasingly complex array of legal situations regarding behavior at school, work, and on the streets as teens become the target of law enforcement. But most kids are unsure of their legal rights.

IN RESPONSE, the State Bar of California has published Kids and the Law: An A-to-Z Guide for Parents, a handbook triggered by a State Barcommissioned statewide survey of 600 California youngsters (ages 10 to 14) and conducted in 1996.

"The survey found most children didn't know a lot about their legal rights," says attorney Anne Charles, a spokeswoman for the State Bar of California. "Most kids, instead of getting their information about the law from their parents, get it from TV and school."

The free, 80-page handbook, believed to be the first of its kind in the state, explains a variety of legal issues faced by teenagers, such as gang colors, curfew laws, juvenile court, loitering, and drugs.

"Most kids don't know what to do [in legal situations]. Even adults don't know their rights, because California is one of the most complex legal jurisdictions in the country," says Tom Nazario, a professor at the University of California School of Law, who authored the guide. "Parents should be aware if kids do get in trouble, and they shouldn't be reluctant to talk about these issues."

Nazario adds that he is seeing a trend throughout many communities to try and keep kids off the streets. "With curfews and zero tolerance areas, the law is making it more difficult for kids to simply grow up," he says.

Sonoma County has had its share of increased, and often complicated, activity involving teens and law enforcement:

ON THE NIGHT of July 3, several Graton teens were among a small crowd of families, adults, and dog walkers, watching the Analy High School fireworks display from the vantage point of the Graton graveyard--an annual tradition--when sheriff's deputies arrived and homed in on the kids. A couple of youths who had beer fled; the remaining teens were all subsequently ticketed for loitering and/or drinking.

Witnesses say the deputies ordered four of the six, whom they'd just ticketed for drinking without administering sobriety tests, to squeeze into the cab of a pickup--without sufficient seat belts--and drive home. Two 15-year-old girls were made to walk home, unescorted, along an isolated dark road.

IN JUNE, Slater Middle School honor student Jackie Young, 12, of Sebastopol, unknowingly brought a Swiss Army knife in her backpack and was suspended because of a strict "zero tolerance" policy against students bringing weapons or drugs onto campus.

The seventh-grader was suspended for a week June 7 after school officials searched her belongings. According to Jackie and her mother, Suzie, they had innocently carried the small knife on a horseback riding excursion in Annadel State Park and forgotten it was still in the backpack.

PETALUMA POLICE and business owners clamped down this spring on groups of teens hanging out in Helen Putnam Plaza, a tiny downtown park. Complaints from merchants and residents spawned proposals to install video surveillance cameras and blaring classical music--the latter already being used without much success as a youth-repellent in downtown Santa Rosa--as possible deterrents.

POLICE WOULD never try [these kinds of] intimidation tactics on an adult," says Joyce Bedler, an adult friend of Radich. "[Amber] doesn't even know her rights--didn't know she could file a complaint."

Sebastopol Police Lt. Jerry Lites , while not familiar with Radich's case, says there has been "a tremendous problem" with teens hanging out and intimidating park-goers. "If kids respected the rights of other people, we wouldn't be down there," he says. "We don't say, 'Today we'll go harass kids in the park.'"

Dillon Chavez, 18, of Graton, was so freaked out when sheriff's deputies ticketed him for dropping a cigarette butt recently that he completely ignored the ticket, an act that only made matters worse. "He had no experience with the law and so didn't tell his mother, and the ticket turned into a warrant," explains his grandmother Mary Moore, a longtime west county activist. "Suddenly the gang task force was running checks on him; he was handcuffed and arrested. "

Chavez's relatives say that, during the booking process, deputies asked whether he wanted to be in a cell with the Nortenos or the Surrenos--referring to notorious street gangs. "If he'd randomly chosen one, it would have been written down that he'd claimed gang membership," says Dillon's mother, Diane Pope.

"We ask, 'If you could be housed with either one, could we anticipate any problems?'" says Sonoma County Sheriff's Capt. Casey Howard, adding that it's a routine question given to everyone for their own safety. "They are absolutely not asked to state a preference."

Even so, other parents have complained that teens have been falsely accused of being gang members by law enforcement officials and specifically by the county task force on gangs, which makes regular sweeps.

Now, Moore says, parents are starting to connect with each other over many of these issues. "I told the kids, if anyone says you can't gather, be polite, take their name, date, and time, and we'll handle it from there," she says. "These kids don't know how to fight back--they just grumble among themselves."

Santa Rosa attorney Marylou Hillberg, who practices juvenile law, says the law has become more stringent over the last 10 years, with more focus on punishment than rehabilitation. Kids should know their rights, she says.

"School authorities can search you with very little reason--some inkling but not as much as a police officer would need," she says. "Also, kids have fewer rights than adults about being stopped in the street because of curfew laws in some towns."

The best advice to kids who are arrested? Stay mum, because it seldom does them any good to make statements to police without an attorney and/or parents present, Hillberg warns. "Police are free to lie to kids to get statements. They may say, 'We've got your fingerprints,' when they don't, and kids are more likely to confess because they've been taught to answer."

Hillberg says that because people tend to be frightened of teenagers, especially in groups, merchants in many towns have complained that youths intimidate their customers. She has witnessed in Sonoma County a "concentrated effort to disperse kids."

Parents also suspect teens are being targeted, specifically in areas that are undergoing developments and makeovers because of business interests. "Graton is a town under reconstruction; people are starting to bring in money," explains Diane Pope.

Parents say deputies have told kids they couldn't gather in groups of more than three. "What's fueling it in Graton is that it's one of the last really funky areas in Sonoma County that's not been yuppified," claims Mary Moore.

Joyce Bedler agrees, saying Sebastopol is also "jumping on the bandwagon of a local police harassment campaign" because of complaints from business owners. "The police are driving [the kids] out of nice safe communities," she complains.

"We're teenagers and we have nowhere to hang out, so we hang out downtown and the businesses don't like it," says Emily Chavez, 15. "Some places are pushing [law enforcement] to get us out."

PARENTS IN GRATON complain that deputies are handing out tickets to teens for trivial matters when warnings would suffice. Moore says that one time several kids (more than three) on the way to a church outing were ordered to disperse by one deputy until the minister intervened.

Sheriff's Capt. Howard says that he's met with concerned Graton residents and that everyone came away with a "better understanding."

He adds that he is satisfied with the department's handling of teen-law enforcement. "Not every violation necessitates a ticket. I try to encourage officers to balance things to meet community needs as a whole," he says. "If groups of 15- or 16-year-olds are out after midnight, there is a reasonable likelihood they will encounter police," he adds.

Howard acknowledges that there have been complaints from business owners about teens congregating, using profanity, and loitering, but he says there are no street gang problems in Graton.

Amber Radich says her experience with police became an ordeal that other teens should try to avoid. "I've never been arrested or in trouble before. I was lied to and harassed before I did anything wrong," she says. At the police department, Amber became angry and told officers, "This is bullshit." She says they told her that her attitude was "failing" and threatened to send her to jail for four days.

She sat in a holding cell for three hours until her mother was notified. "I wish I'd asked for an attorney," says Amber. "I didn't know. I was upset and overwhelmed by the whole idea I was being arrested. I just wanted to get back to work."

HOW SHOULD TEENS react to a similar situation? "Don't talk unless you're spoken to and be really, really polite," Amber warns. "Police don't like teenagers as a group, and they're just waiting for you to get a stereotypical teenager's attitude."

Attorney Mitch Genser of the Children's Law and Mediation Center in Santa Rosa says as adults perceive more violence, drugs, and school expulsions, they are cracking down harder with policies such as zero tolerance, which could backfire. "When you set up lines in the sand and say, 'When you do X, that is the consequence,' you catch into a net a lot of kids who aren't part of the violence, " he says. "When some kids screw up, other teens have to pay the price."

When examining all the deterrents congregating teens face from communities, from surveillance cameras to blaring Beethoven, Kids and the Law handbook author Tom Nazario is a mite sardonic. "We're lucky kids don't have a right to vote," he comments. "Otherwise there wouldn't be a lot of this."

[ Sonoma County Independent | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

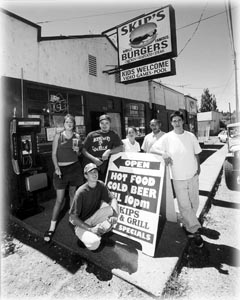

The Kids Are All Right: Graton teens stand to lose this popular hangout.

What the numbers say about kids and crime.

For a free copy of the Kids and the Law handbook, call 1/800/455-4LAW.

From the Aug. 27-Sept. 3, 1997 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.