![[MetroActive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

![[MetroActive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Features Index | Sonoma County Independent | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Courting Trouble

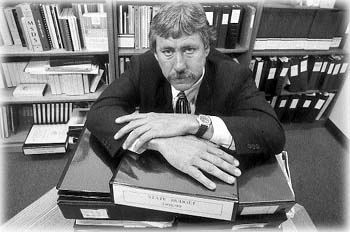

Hanging On: Sonoma County court administrator Greg Abel.

Tougher sentencing and a state budget cut could spell disaster for county courts

By Paula Harris

SONOMA COUNTY COURT Executive Officer Greg Abel is not pleased. "Don't get me started talking about state funding or you'll probably hear more than you care to," he grumbles. "A few months ago, the year was filled with promise, the state was coming out of a recession, and it looked like there was a lot more money to hand out," he recalls. "But the state has made courts dependent on funding and hasn't lived up to its promises and obligations--it's put us in a terrible situation."

Seated at a table stacked high with files, the weary county courts administrator pulls out statistics summarizing Sonoma County's trial court funding, to illustrate his reaction to reports that Gov. Pete Wilson will veto a bill that would have bailed out cash-strapped county and city courts.

The plan--a second attempt in two years--calls for the state to assume full funding of trial courts and then pay for any future growth. It was a measure widely expected to pass, but now the future of court systems statewide hangs in the balance.

"Everyone said last year it would have to pass this year or it would be a catastrophe, so we hung on," says Abel. "Now, there are a lot of angry judges and court administrators out there."

The court trialfunding measure would have boosted the ratio of fiscal support the state gives counties to run courts, from about 35 percent this year to 60 percent next year, and would have made the state responsible for full costs of running court operations in the state's smallest counties.

A $450 million increase would have been given by the state to run courts, with counties splitting $388 million. Abel says the bill would have been worth several hundred thousand dollars this year for cash-strapped Sonoma County courts and would have risen each subsequent year. "It would have been a great bill for the counties," he says. "It would have capped counties at 1994-95 levels, and it would have been extremely valuable to Sonoma County in the long term."

THE SITUATION is putting stress on the entire county system, especially the general fund departments, which are funded entirely by the county and not by the state," says Sonoma County Public Defender Louis Haffner.

He reports that the county Public Defender's Office is seeing a leap in domestic violence cases owing to changes in the law that eliminated diversion programs. "It's one of the fastest-growing segments because of increased public awareness and changes in law enforcement policies," explains Haffner, adding that about 40 percent of his staff's time is spent on domestic violence cases.

During Tuesday's budget hearings, the Sonoma County Board of Supervisors voted 5-0 in support of a new Domestic Violence Court. It will cost $210,000 to start the program. So far, county funding is unavailable owing to a $6 million budget deficit, but the supes have pledged to find a way to pay for it. The Domestic Violence Court--the fourth in the state and the first in Northern California--will be modeled on the Drug Court. It is scheduled to begin Nov. 1 if funds can be found.

Lorene Irizary, director for the Sonoma County Commission on the Status of Women, is elated with the development. "We'll have a better system to respond to victims of domestic violence, cases won't get lost in the system, and there will be trained experts so that victims won't be revictimized," she says.

Judge Robert Dale, who will preside over Domestic Violence Court in the mornings and Drug Court in the afternoons, says the initial funding will pay for two probation officers, a deputy district attorney, and a deputy public defender. "Other than that, we'll use existing resources," he explains. He adds that the Domestic Violence Court was given high priority in the budget hearings because it's expected to eliminate delays and improve efficiency in dealing with cases.

"Now, instead of being distributed alphabetically between three judges, all cases will appear in front of me," says Dale, adding that he expects to be very busy.

There have been no new state-funded judicial officers added since 1985, and administrator Abel laments that a much-anticipated judgeship bill that had placed Sonoma County 10th on a list to add a new judge (one of 40 new judgeships statewide), appears to be "dying on the vine."

Also, Abel says, if the state had come through with the funding, Sonoma County courts would have added some 10 new staff positions, including much-needed legal processors, court room clerks, and court reporters. Several years ago, the department had to cut 27 positions, which saved the county $1.3 million per year, but resulted in workload surges and reduced services.

"People are having to work themselves crazy, and the services are probably not the same," Abel says. "We're having difficulty maintaining critical service areas--juvenile, family law, jury, records management, courtroom clerks, computer services. All these would be priority areas to fund." There are 168 permanent positions in the Sonoma County court system, including judges. "I couldn't tell which area to cut a position if my life depended on it," states Abel.

Services are being stretched while Sonoma County has been experiencing major increases in felony filings. The system is still reeling from a recent 30 percent growth in felony filings, which tapered off in 1995-96, but rose again to almost 20 percent in 1996-97. Misdemeanor filings are also up (by 6.8 percent) for the first time in four years. In addition, juvenile cases have increased substantially.

Although the high-profile Richard Allen Davis kidnap and murder case cost $2.4 million, the state paid through special legislation, explains Abel, but he adds that the Robert Scully murder case has cost the county about $1.2 million.

The state started funding the courts in 1989. In 1991-92, state funding was set at 50 percent and was supposed to grow in 5 percent increments each year until it reached 75 percent, but that never happened. The county became dependent on the state, and later had to absorb costs.

The department has consolidated municipal and superior courts and clerk of the court, and bridged much of the financial gap between 1994-95 and 1997-98 levels with increased civil filing fees. The Sonoma County court system now gets about one third of its funding from the state, another third from the county, and the rest from fines, fees, and other charges

According to Abel, after hours of staff work and wading through red tape, the fines and fees are sent to the state, processed through various formulae, and then mostly sent back to the county. He says the real net value in the state budget is worth only about half a million dollars to the county. "We get money re-routed to us, and there's not enough to justify the work load associated with it," he explains.

Abel adds that although the Sonoma County courts system is not bankrupt like those of some counties, it's going that route. "We had the opportunity to get back some of what we lost [with state funding]. Now that's fallen by the wayside," says Abel. "The state came in with a boom and slowly it's eroded--some of that we've had to eat. We had the opportunity to partially restore cuts, and now that's gone."

[ Sonoma County Independent | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

Michael Amsler

From the August 21-27, 1997 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.