![[Metroactive Features]](/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | North Bay | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

Acting Civil: Participants in Civil War Days at Duncans Mills may be Union or Confederate fighters during the weekend, accountants or travel agents during the week.

Dress Reversal

In loyal groups across the country--and the county--adults are taking dress-up to the next level

By

'Civil War--next right turn."

Those words, emblazoned on a large, hand-painted sign not far from the sleepy town of Duncans Mills, have led me to a vast, entirely empty parking lot at 7:30 this morning. Another sign, hoisted up near a little creek-crossing bridge, announces "Civil War Days." Sponsored by the National Civil War Association, one of several such organizations in the United States, this annual event is one of the state's most popular homages to Civil War history, Civil War combat, and Civil War fashion.

"You're early," notes a sleepy parking attendant, having waved me across the lot and into a convenient parking spot."Are you planning to stay for the battle?"

"I'm going to be in the battle," I reply, pulling my brand-new black boots from the car and stepping out onto the dusty lot. Having accepted an invitation from my friend Walter Masten--who, with his wife, Bridgette, has been involved in Civil War reenacting for a little over three years--I'm about to become a recruit in the Richmond Fayette Artillery company. I'll be fighting for the Confederacy today, and as I understand it, I've already been assigned to a regiment of gunners, as in "cannons."

Nearby, I can see two men in blue Union uniforms, walking a horse toward the battlefield, and a row of tents wreathed in smoke from a hundred separate breakfast fires. The 1800s have apparently already begun. With a few short strides across a dew-slicked field, I leave the lot behind and step into the colorful, alternative reality known as Civil War reenactments.

In short order, I've located Walter and Bridgette of the Richmond Fayette Artillery (affiliated with the American Civil War Association), both of whom are dressed as soldiers--"As a woman," says Bridgette, "I can dress as a woman or as a man"--and both of whom will be setting off the cannons with me when the battle begins in a few hours.

But first Walter says, "Let's get you suited up."

Outside the quartermaster's tent, relaxing under a white canvass awning, a group of folks in Confederate soldier garb are sipping coffee at a wobbly wooden table. Nearby are several battered trunks. The quartermaster, a strapping fellow named Ken, stands up to eye me from head to toe, then tosses open a trunk and begins handing me various uniform pieces: a pair of gray trousers, a thick woolen shirt-jacket, a pair of suspenders, and a classic black-brimmed, gray wool Confederate soldier's hat. Examining the well-worn items, I realize immediately that in the Civil War years, clothing size must have been a relative concept.

"If it's too big or too small," remarks one lounging soldier, "it's perfectly period."

Clutching my jerry-rigged uniform, I follow Masten back across the field, past a dozen tents where people--men and women, young and old--are relaxing, polishing guns and swords, scarfing food from metal plates, or generally milling about, all in various states of costumed readiness. Here and there, women in gingham dresses are hugging, talking, or flirting with men in gray uniform. After a few minutes in the Mastens' relatively spacious officer's tent--inside which not a hint of the 21st century is visible--I emerge and stand ready for my first inspection.

"Not bad," says Masten, giving me a quick inspection before pulling me out to the field for cannon training. My cannon has been dubbed Nostradamus, and it's the real thing. After training for an hour as the day grows warmer, I am required to take a written safety test. The first battle of the day is scheduled for 1 o'clock, so I have time to gather a few practical pointers from my fellow confederates, many of whom are seasoned reenactors.

"Battles generally last until somebody screws up," jokes Chris Lacklan, who's been doing reenactments for about five years. On the whole, he surmises, the average battle lasts between an hour and 90 minutes. "Though when people get into the heat of the thing," he says, "a battle can last all day."

I am told that, should I be shot by a Union gunnery squad during the battle, someone of higher rank will let me know and will tell me whether I've been killed outright or just mortally wounded. The cannons use real gunpowder, enough to sound a big bang but not enough to cause (real) mortal wounds--unless someone gets too close.

"Mortally wounded is more fun than dead," says Paul Vankas. "If you're mortally wounded, at least you can yell and scream and crawl around a little."

"If you do get killed, make sure you fall face down," someone else suggests. "Believe me, unless you have a lot of sunblock on, you don't want to be lying there face up for an hour."

Adds Masten, "Rule number one: Be safe. Rule number two: Have fun."

Have fun.

Not everyone would agree that dressing in wool on a hot summer day and blasting cannons at people in similar outfits while taking turns pretending to die is fun. Still, few of us have not experienced the basic pleasure to be had in playing a little bit of dress-up, though most folks--actors, drag queens, and Rocky Horror fans excluded--put the urge aside after childhood, dragging it out again only at Halloween, perhaps for the benefit of the kids.

How then does one explain the fact that there are currently over a hundred independently produced Renaissance fairs taking place each year in the United States, along with hundreds of small city- or college-sponsored fairs and countless meetings of the Society for Creative Anachronism devoted to Medieval culture? There's the Great Dickens Christmas Fair in San Francisco, the Roaring '20s-themed Great Gatsby Festival in South Lake Tahoe, the Wild West-themed Topton Shoot in Pennsylvania, and the annual Black Powder Shoot and Mountain Man Rendezvous in Yosemite--and, of course, all those routinely occurring Civil War reenactments--all of which involve adults dressing up in historical outfits and acting as if they were characters from a history book.

One has to wonder if the steady rise of such freeform costumed spectacles can't be attributed to a need some people have for a safe, socially sanctioned context in which to fulfill the innate desire to become another person for a weekend or two.

"It's OK to dress up on Halloween," muses costume aficionado Laura Brueckner, of Novato. "It's OK to dress up for a parade or something like that, but any other time, it's just not done, it's not acceptable--not for adults. The Renaissance Faire, the Dickens Fair, the Civil War reenactments, all of these period events serve to give innately creative people a place where their research and their enthusiasm and their creativity are rewarded. Some people go at it from the historical reenactment standpoint, but that's a creative urge itself--it's creativity clothed in history."

She speaks from experience.

Having spent nearly half her lifetime performing in costumed period events, Brueckner--who insists that she was once so shy she wouldn't perform in public unless wearing a mask--is now a singing, dancing, and acting member of a "period musical comedy" troupe called the Stark Ravens Historical Players and serves as promotions manager for As You Like It Productions, the Novato-based company that produces the Heart of the Forest Renaissance Faire in Santa Barbara and Novato. To hear Brueckner speak, one might think she was describing a form of therapy rather than a historical reenactment.

"It's true," she says, "it's like therapy sometimes. It's like Dumbo's magic feather! You put on a costume and a hat, and it's just enough so that you can feel safe to step out and be creative. That's all people need to express their creativity, a sense of safety. Everyone is able to inhabit a character that has attributes they'd like to express in their everyday lives but can't. We have accountants with master's degrees, people who make six figures a year, who come out here every week to dress up as a rowdy ale wench, because the life they've chosen holds no place for that kind of behavior."

Such events as the Renaissance Faire and the Civil War Days, Brueckner argues, can and often do become incredible confidence boosters.

"The social environment at fair is incredibly, ridiculously supportive. It's wonderful!" Brueckner says. "And once you start picking up confidence from all that support, it can't help but start bleeding over into the rest of your life. You can't stop it. There are now whole generations of people who, because they once got to put on this hat and this jerkin and this pair of trousers, because they were asked to hawk in front of a booth at the Renaissance Faire, they now have a different relationship with speaking to people."

Alberto Melendez is the guild master of the Knights of Santiago (www.knightsofsantiago.org). The official Northern California Spanish guild, the Knights of Santiago appear at numerous smaller-scale Renaissance fairs around the state, where they get to play that group most hated by the Elizabethans--namely, the Spaniards.

As we speak, Melendez is packing for a weekend at the Pittsburg Scottish Renaissance Faire out in the East Bay, where he'll be teaming up with about 25 of his fellow guild members, to set up camp and the fair and create a bit of historical mayhem.

"At the fairs, they like to use us as a catalyst," says Melendez. "'Ooh, watch your purses! The Spanish are around.'"

Born in Puerto Rico and raised on the East Coast, the 38-year-old Melendez is a bus operator for Golden Gate Transit. He began attending Ren fairs almost 13 years ago and was immediately drawn in, largely by the desire to dress as one of the actors.

Melendez admits he was never the kind of person who dressed up for Halloween or enjoyed going to costume parties. "As a kid, I was kind of deprived a lot," he says, "so maybe this is my way of making up for that." Melendez became hooked on Renaissance dress, trying on various styles and roles until his research revealed the Knights of Santiago, with their vaguely menacing black garments and capes and feathers. Now he spends most of his spare time attending fairs, developing his character or adding to the expanding costume collection of the guild.

"You have to be a bit of a history buff," Melendez admits. "But it goes further than that. In my guild, what I hear the most is people saying, 'We're working five days a week, blah, blah, blah, all year long, and on fair weekends we get a chance to escape, to be somebody else, to play and be in the spotlight for a while.' For two days, I can get away from work. I can be a Spaniard, I can be a rogue, I can flirt and drink and have fun. Also, after a while, seeing the same people at different fairs, it eventually becomes like going to a family reunion."

Literally. Melendez met his wife at the Renaissance Faire, and even had a Renaissance wedding with 300 friends and family members attending in costume.

A naturally gregarious and friendly person, Melendez says that he was once much less outgoing and amiable. It was at the fair, he insists, that he developed a skill for interacting positively with other people.

"I learned that the more positive things you say about a person," he says, "no matter what they look like or how they are behaving, they will respond positively to you. I use that almost every day now. If somebody gets on the bus and they're in a bad mood, I say something positive, I pay them a compliment or something--I basically just charm them. I learned how to do that at the Renaissance Faire."

Dr. John Amodeo, author of The Authentic Heart, is a psychotherapist with a special interest in how people lose touch with and regain a sense of their authentic selves. Even he affirms that pretending to be someone else can sometimes be a good thing.

"Dressing up as another person has the potential to expand a person's sense of self, to get them out of their small egos for the moment," Amodeo says. "Doing historical reenactments allows them to play with their sense of self, but it also helps take us back to a time--the Renaissance, the Civil War--when people did not have to wrestle with the high-stress corporate world or with the overpopulation, noise, pollution, and traffic that are routine pieces of the modern age."

As for Brueckner's observation that such events can help shy people learn to be more outspoken, or that by pretending to be charming and charismatic a person with bruised self-esteem can slowly embrace a sense of themselves as authentically charming and charismatic, Amodeo agrees.

"There's a principle in therapy called 'acting as if' or 'faking it till you make it,' as they say in 12-Step Programs," Amodeo says. "If you act as if you are confident, even if you don't feel confident, gradually you can become that, you can develop that quality of confidence as you put it on. It's a very powerful technique, and perhaps these dress-up events give people the opportunity to do that in a safe environment.

"The positive part of these kinds of events," Amodeo adds, "is that they get people in touch with a different part of themselves and loosen their attachment to some unhealthy, rigid roles they might be playing in their life. Playing dress-up at the Dickens Fair or wherever really can be used to free up a larger sense of possibility in your day-to-day life."

David William Entriken makes it perfectly clear. "The uniform I wear is clothing, not a costume," he says following the battle, a relatively short affair, of which we Confederates, I am told, are the winners. From my vantage point on the battlefield, ears crammed with earplugs, all I can report is that war, even make-believe war, is very, very loud. As horses raced back and forth, and various squads of soldiers, Blue and Gray, advanced and retreated, I remained focused on old Nostradamus, careful to do my job properly and keep the thing from exploding and actually killing us all. That said, the whole experience is thrilling, and my inner reenactor, having long lain dormant, has now been reawakened.

I'd enlist again in a second.

A seven-year veteran of Civil War reenactments, Entriken, an electrician who lives off the grid near Sonora, has played the spectrum of costumed (er, make that historically clothed) period events. A former Society of Creative Anachronism member and a longtime participant in Ren fairs, he's gone by a lot of different names. Today, as the Civil War Days begin, he's First Sgt. D. William Entriken. At Mountain Man Rendezvous, he's known as Electric Beaver, and he goes by Tin Horn for events sponsored by the Old West Living History Foundation. While he acknowledges that reenacting could be seen as a form of therapeutic dress-up, a grand-scale playtime for adults, he prefers to focus on the historical appeal of the thing.

"This is our hobby, sure," Entriken says. "All hobbies are play-time--hiking, skiing, kayaking. It's all play. But the reason we do this is because the history is important. The Civil War changed our country forever. But most people know almost nothing about it."

Abraham Lincoln agrees. He's been mingling with visitors over in the settlers encampment, where onlookers can view demonstrations of historic crafts, buy a book on Civil War battle strategy, or chat with the president of the Union and his wife, Mary Todd Lincoln. Played by Mike Ray and Alice Tripoli of Diamond Springs, Calif., the Lincolns consider themselves to be a walking-talking history lesson and gleefully affirm that reenacting is now less a hobby for them than a way of life.

"When a child reads a history book," says Ray, "their eyes glaze over. But if they see history right in front of them, they'll never forget it." Approached by a couple in modern-day dress, he stops to swap a few jokes. ("The show was to die for," he tells them conspiratorially, "but the view from the balcony gave me a headache.") Though a bit shorter than Lincoln is reported to be, Ray looks remarkably like the real thing, and yet his repertoire extends far beyond playing just one character.

"Depending on the time of year and the particular event," he says, "I am a president, a rebel cannoneer, a monk, a Mennonite, an Irish railroad worker, a mountain man, a town drunk, a '49er, and a riverboat gambler."

Others are content to be just two people--their modern-day selves and their Civil War selves--and for many, the history they are playing out and the distinct satisfaction they get from putting on that uniform cannot be separated.

"Men get into reenacting, and they all of a sudden get real creative. They start building things," says Jim Andrakso of Sonora, who builds his own costumes, weapons, leather packs and other gear. "They start sewing! As a kid you dress up and play all the time, but as an adult, that's harder to do. Life is stressful, and for a lot of us, there aren't that many opportunities to be creative. Out here, I get to be someone else, and I get to enjoy being myself at the same time.

"Where else am I going to go to do all that?"

[ Santa Cruz | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Photographs by David Templeton

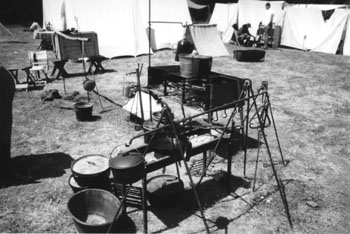

No McDonald's Here: Reenactors experience 'living history' whole hog, including sleeping in tent and cooking their own food.

From the August 21-27, 2003 issue of Metro Santa Cruz.