![[MetroActive Features]](/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Photos by Michael Amsler

Dispatch from

the Farm Front

One farmer's views on the demise

of the North Bay's agricultural heritage

By Shepherd Bliss

GIANT YELLOW BULLDOZERS have pounded the ground loudly behind my small, green, west Sonoma County farm for weeks. As I patiently pick berries, aggressive builders widen a narrow, dirt country lane (where neighbors used to stroll amid majestic oaks) to clear the way for more huge, expensive houses. Eager developers cut down tall black oaks and spreading valley oaks to make room for a shiny new road in this once secluded community. They shatter our rural peace, bringing stress to an otherwise serene scene. Not since serving in the U.S. Army during Vietnam have I endured such relentless shaking of the ground.

This feels like war against the land and its many natural occupants--further ordering it for human control, domination, and habitation.

The beauty of the oaks and the meandering lane have been replaced by monotonous, one-dimensional levelness. "What's that new freeway doing back there?" one regular customer bemoaned.

I miss quietly sauntering down that rolling country lane and resent the spread of gated estates into formerly more open communities.

My farm has been invaded by working machines. My soundscape has been occupied by loud, ugly noises that have replaced the songbirds. I put on earmuffs to keep the sound out, but I still hear it and feel it rattling my dishes. There is nowhere to hide; this is my home.

Wildlife has fled roadside habitats and come to the property to which I hold title. Though they have damaged my crops and livestock in search of food, water, and shelter, I receive them and know that their stay will be temporary. When humans build, we displace much of nature and wildlife, most of it silent and invisible. Innocent animals must then find new habitats, if they can. Uprooted vegetation, of course, perishes.

I walk the land each day, feeling directly with my feet, watching life grow. I touch animals, plants, and soil each day, feeling them with my bare hands. Sights and sounds are less beautiful here than they used to be, and I smell more pollution in this country air. Stars are less visible at night. These things get to me. Sometimes I am rough, forcefully pulling "weeds" from the ground and protecting livestock from predators. My feelings are more raw and close to the surface than when I lived in the city. Memories of loss emerge. So what follows is not always diplomatic.

I get angry, beneath which is a deep sadness.

IN THE EARLY 1990s I bought this rundown farm outside Sebastopol and restored it to a viable business with the support of such groups as the Community Alliance with Family Farmers. I could never afford such a farm today, with prices for land driven so high by the alcohol-beverage and high-tech industries.

Formerly independently owned local wineries have been bought up by powerful "spirits" corporations like Seagrams, Brown Forman, and Allied Domecq, and integrated into the global alcohol industry. The British Allied Domecq recently moved into its new 6.6-acre warehouse in Windsor, the largest single building in Sonoma County and a sign of similar monstrous buildings in the future. Mammoth high-tech corporations from around the world are buying up small, local telecom startups for billions of dollars. Alcohol-beverage and high-tech incursions are the one-two punches to Sonoma County's environment, local agriculture, and rural legacy.

I usually appreciate the harvest--working hard outside all day, seven days a week, sunup to sundown, falling asleep under tall, fragrant redwood trees. In addition to my crops, my field is full of poppies, lupines, and other wildflowers that blow in with the wind, and even supports coyote bush and oaks planted by jays and squirrels. Working the land, looking into the skies, and extending my body brings both exhaustion and serenity. But the 2000 harvest has been an assault on my senses and psyche--tiring me out and making me irritable.

People follow the local Farm Trails and come directly to Kokopelli Farm for organic berries, apples, eggs, and tours. I enjoy bringing a full, aromatic tray of berries up from the field and watching mouths and eyes open wide as saliva begins to flow. "Yum, yum" sounds of appreciation follow. People from the city come to the farm and pick their own, emerging with a wide smile surrounded by a deep purple color. Or they gather eggs of various sizes and colors from over 15 breeds of free-ranging hens, noticing how my jungle fowl look like raptors from the age of dinosaurs. People return home refreshed by this rural, pastoral experience among abundant plants and instinctual animals. They savor the unpredictable elements, such as wind--that exuberant dance partner of the trees.

Soothing farm sounds from chickens, cows, horses, wild birds, and blowing leaves were supplanted this year by loud earth-moving machines with their manufactured sounds of "progress." Headaches and a wounded feeling replaced my usual farm pleasures. The high-pitched pinging of huge machines going backwards and warning of danger is especially damaging. I moved to the country seeking solitude--away from such relentless industrial ravages. Now Sonoma County is being suburbanized by various forces, including the high-tech gold rush.

As a result, this year the median price of homes in Sonoma County increased more than anywhere else in the nation, and Forbes magazine listed us as the country's third most dynamic economic region. This is not good news for the wild birds, native plants, and small farms already here, many of which will be displaced. Sonoma County has been discovered, internationally, for its income-producing capacity. Tremendous growth will follow.

We are accelerating down the Silicon Valley highway.

Santa Clara County used to have a rich, vibrant agriculture based on over 6,000 small family farms. Now it offers congested traffic, the highest housing costs in the nation, and the most federal Superfund hazardous-waste sites in the United States--but hardly even a fruit stand.

I AM ACCUSTOMED to seeing mainly trees out back, a few black-and-white milk cows, a couple of large golden Belgian workhorses, and many quail and deer, as well as hawks, vultures, and various other birds. Occasionally I see a fox, skunk, raccoon, mink, snake, gopher, badger, or other nocturnal animal. After the months of destruction to build the road and houses, I wonder how things will change. I have been busy planting trees along my perimeter for years, but I will never be able to hide the cars, the swelling tide of people, and all the activity they bring.

The "spoilers," to use California poet Robinson Jeffers' description, are multiplying. In "Carmel Point," Jeffers laments, "This beautiful place defaced with a crop of suburban houses. How beautiful when we first beheld it."

We are losing the beauty of Sonoma County, as have other areas once they are "discovered" and transformed.

I used to enjoy driving around, especially in the west county with its scenic, diverse beauty. Now I feel nature receding, as huge houses and regimented, precise vineyards replace forests and orchards. I never know when I am going to turn a familiar corner and see some new industrial vineyard or starter castle. A sense of loss gnaws at me. Being surrounded by trees is inspiring, but all the building in the county saddens me.

Giant corporations, such as Finland's Nokia, the world's largest maker of cell phones, plan to fill in wetlands to build office complexes. Petaluma has already filled in many wetlands, including those violated to construct its main telecom center, ironically named "Redwood Business Park." Redwood trees are beautiful, but this faux "Redwood Park" is ugly. The best buildable land has already been built out.

The telecom gold rush has just started and threatens to destroy much of the county's remaining natural beauty and existing rural culture. More global corporations will follow.

Sonoma County's sense of place is changing, rapidly and dramatically, but not for the better. The natural environment here historically has been diverse--rugged coast, redwoods and oaks, rolling hills, rich soils, ample rain. Into that came an agriculture that developed a rural culture around it. Both the original natural environment and the rural legacy are now threatened, especially by the high-tech onslaught and the wine monoculture.

THE ALCOHOL-beverage industry's talk of aerial spraying of highly toxic pesticides to combat the glassy-winged sharpshooter, a vineyard pest recently discovered in the North Bay, poses another threat to traditional farming. Such spraying would harm organic gardens and farms, doing considerable "collateral damage" to beneficial insects, and to animals, humans, and our county's soul.

Even the possibility of spraying is unsettling, especially since authorities can declare an "agricultural emergency" and trespass on private property without permission. We already have an "agricultural emergency," but it is not caused by a tiny "pest." As recently as 10 years ago, wine accounted for only 20 percent of Sonoma County's agricultural revenue; it is already over 50 percent and moving toward Napa's 90 percent. The wine monoculture is Sonoma County's "agricultural emergency."

Although scientists and environmentalists warned against transforming Sonoma County's diverse agriculture into a monocrop, the alcohol-beverage industry took a gamble. It may lose that gamble, though its political operatives in Washington, Sacramento, and Santa Rosa have pledged millions of our tax dollars to try to bail it out and to punish those of us who follow organic and sustainable farming practices. A better solution would include a moratorium on planting any more vineyards in Sonoma County for now.

More people with their technology and machines means less nature. Exotic, non-native plants--including wine vines--draw "pests," such as the glassy-winged sharpshooter. Even if this particular insect is eliminated, others will follow to restore nature's balance to an overcultivated region where more of nature is pressed into service to humans. The Pierce's disease that the sharpshooter brings is not new; it decimated 40,000 vineyard acres in California in the l880s, and no cure is yet known. Chemical agriculture is on a collision course with nature. The sharpshooter is more a symptom of a larger problem than the problem itself.

Perhaps the glassy-winged sharpshooter is actually a gift horse in disguise. Perhaps this tiny insect and the arsenal that is being prepared to combat it will wake up more people to how degraded our view of nature has become, as if it exists mainly to serve business and the global economy--at any cost, even that of our own health and soul.

INSTEAD of merely delivering a blow against the alcohol industry, perhaps the sharpshooter's hit will be against industrial/

chemical agriculture by stimulating a mass movement against it. I have heard more talk of civil disobedience against aerial spraying than I have heard in a long time. Trainings for local nonviolent action against spraying are now scheduled to start.

In saying these strong things about the alcohol-beverage industry, I do not mean to dismiss the many good vineyardists and authentic growers in the wine industry. A sustainable wine industry will be built on the labor of such good farmers, even if the sharpshooter harms the current overplanted industry.

This year I lost my main customer--a local grocer with three stores who sold out to a huge chain. Though promising it would continue to support local farmers, that chain now imports fruit from Europe and Latin America.

I feel things closing in on me, a way of life dying.

Death is as common on farms as in wars. Plants and livestock are vulnerable and perish. Growth can emerge from death and decay. But it is hard to get used to death, especially the death of woodlands and orchards mowed down to accommodate houses and industrial vineyards, the twin threats to Sonoma County's quality of life and environment.

I drive up to the graveyard on a hill in the town of Bloomfield and to a cemetery outside Graton, still surrounded by apple orchards, but probably not for long. So much is dying in Sonoma County today that we will not be able to bury it all in the area's small rural graveyards--signs of the past. Many deaths accumulate in my soul, settling into a place where their lives will be remembered.

New farmers used to come to Sonoma County every year. We would welcome them and educate them about the tasks of tending the ground and its bounty. Most food growers can no longer afford land here. The local economy is being replaced by the global economy. We are losing control of the making of decisions that influence our lives and the land that we live on.

Now Sonoma County gets many new high-tech people and some new winemakers each year. But the wine industry has only a small agricultural component; most of those who prosper in wine are not farmers with dirt under their fingers, but lawyers or businessmen good at making money.

Some of my neighboring farmers have already moved away--seeking the country living they once had here. I recently lost my best source of manure for fertilizer. Traditional farmers depend on a network of relationships with people, plants, animals, and the elements; when those relationships end, a local farm economy is endangered.

Sonoma County is becoming what Kentucky farmer Wendell Berry calls a "colony." Berry describes "the power of an absentee economy once national and now increasingly international." He observes, "The voices of the countryside, the voices appealing for respect for the land and for rural community, have simply not been heard in the centers of wealth, power, and knowledge."

The colonization of Sonoma County is changing our socioeconomic structures and culture. I wonder if global corporate power and all its wealth will make it difficult to pass legislation--such as the modest Rural Heritage Initiative, the growth measure that will appear on the November ballot--that would help preserve rural culture by keeping control of Sonoma County's future in the hands of local people.

Small family farming is unfortunately on the way out--in Sonoma County, across the state, and throughout the rest of America. Our culture has been based on that agrarian tradition. I already miss the vibrancy I once felt and lament the loss. Remnants will remain. A few hardy farmers will continue in agriculture, in the old ways.

Blessings to them.

[ Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

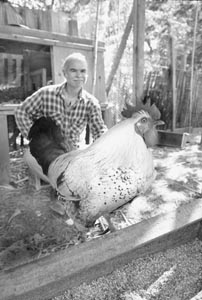

West county state of mind: Kokopelli Farm owner Shepherd Bliss contends that in the rush to accommodate growth in Sonoma County, many of the simple pleasures that lured us here in the first place are being lost forever.

West county state of mind: Kokopelli Farm owner Shepherd Bliss contends that in the rush to accommodate growth in Sonoma County, many of the simple pleasures that lured us here in the first place are being lost forever.

Shepherd Bliss is the owner of Kokopelli Farm. He has written

for the Independent on the corporatization of the

wine industry and other topics.

From the August 17-23, 2000 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.