![[MetroActive Movies]](/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | Show Times | Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Living Legend

Wine Country Film Festival celebrates the outsized career of Kirk Douglas

By Richard von Busack

KIRK DOUGLAS hails from a time when the movies were big, in a way they aren't now. Douglas, who will be

honored with a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Wine Country Film Festival on Saturday, Aug. 12, channeled the outsized emotions of a wide-screen movie age. He had those fierce eyes, the most indomitable chin in movie history, and teeth that looked like they could take a bite out of a granite boulder.

Douglas' The Vikings opened in 1958 in New York at one of those long-gone theaters where thousands could sit together and watch a movie. Above it was a marquee--and if you're under 25 you've never seen how enormous New York theater marquees once were. They could be 50 feet wide and 40 feet tall, the name of the theater crawling up the side of a building in blazing letters visible for a mile.

Above this sizzling monstrosity of screaming neon and high-voltage electricity, imagine an immense billboard with the curved prow of a life-sized Viking ship bursting out of it. A half-ship hanging "ten stories," says Douglas in his autobiography, above the sidewalk. On the opening night of his movie, Douglas had himself pulled up to the ship by rope, where he broke a bottle of champagne on the prow. Here's the punch line of the story, as Douglas writes it: "In those days, that seemed like nothing to me."

The easiest way to describe the character of Kirk Douglas onscreen is as a "postwar heel," as Petaluma's own Pauline Kael described him. "Antihero" is too weak a term for Douglas; more often he was more like an antivillain.

Not that Douglas was always just a tough customer onscreen. He acted the gamut of uncivilized men, from seething barbarians to jolly sailors (as in the fine adaptation of 20,000 Leagues under the Sea). Douglas also played Spartacus and the proto&-Jake LaMotta boxer in Champion. Among these tormented characters, he assayed a version of van Gogh, sacred yet irascible, in 1956's Lust for Life.

Douglas can sometimes be too much for the tastes of the modern audience. If Douglas draws so much rage from his youth, as he says in his 1988 autobiography, The Ragman's Son, maybe his acting is like the big emotions of our immigrant parents. He shows those sentiments that embarrass comfortable sons and daughters; he displays the great appetites that dismay well-fed children.

He was born Issur Danielovitch, though he sometimes answered to Isidore Demsky. He was one of seven children of illiterate Russian immigrants, Jews in the Wasp-run factory town of Amsterdam, N.Y. The man who later became Kirk Douglas describes his father, an alcoholic junkman, as a "bulvan." Here's how Leo Rosten translates the Yiddish word, which Rosten says is also spelled "bulvon": "a gross, thick-headed, thick-skinned oaf. . . . No English word carries quite the sneer of bulvon, or quite the implicit devaluation of brute strength. . . . A bulvon has no sensitivity, no insight, no spiritual graces."

The light in this household was Douglas' mother, whom he loved so much that he named his production company, Bryna, after her. In college, he was on the wrestling team and got into theater. After the war--in which he was an officer on a submarine destroyer--Douglas returned to the stage in New York and then came to Hollywood and found success.

Beginning as a postwar heel in film noirs, Douglas prospered in Westerns, always as a smooth Doc Holliday&-

type dude killer. In later Westerns, Douglas turned these interpretations baroque. He played a flagellant in 1967's The Way West. One of the only things both Kael and Douglas could remember from the '67 Douglas/John Wayne movie The War Wagon was that his gunman villain was so fancy that he wore rings on the outside of his leather gauntlets. In other movies, Douglas lost piece after piece of himself, like the Tin Woodman in the Oz books. "He left a finger in [Howard] Hawks's The Big Sky, an ear in Lust for Life, and an eye in The Vikings," critic David Thomson notes in A Biographical Dictionary of Film.

Douglas' trick was showing us the best qualities of a bulvan, the stoic endurance of physical pain, as well a physical man's exuberance, lustiness, and strutting intensity.

At worst, that self-confidence can become arrogance. Douglas' 1988 autobiography pays back many directors and writers who didn't see things his way. But somehow the actor missed Martin Amis, who wrote the script for Douglas' 1980 flop Saturn 3. Amis writes about a Douglas-like character in his novel Money.

The big star changes the focus of the modest, realistic little working-class Londoner film the novel's protagonist, John Self, is writing. The star insists on a nude scene, stripping to convince Self: "Does this look like the body of a 60-year-old man?" It's fiction, but note that the 64-year-old Douglas did a nude scene in Saturn 3.

Douglas is devastating on the subject of Stanley Kubrick complaining for decades about not being in complete control of Paths of Glory and Spartacus. Yet these two films were better than many Kubrick did on his own watch, so Douglas obviously knew something.

Douglas is bringing to the Wine Country Film Festival a favorite movie, 1962's Lonely Are the Brave. The film is based on the novel The Brave Cowboy, written by Edward Abbey before his days as the poet laureate of Earth First! In The Ragman's Son, Douglas says that few of the movies he loved the most made much money. Very well, that's the feeling any filmmaker has toward orphaned nonhits. Except in this case, Douglas is right again--Lonely Are the Brave is one of his best.

As a last cowboy on a last ride, Douglas' John "Jack" Burns is a lady's dream of a hero--courtly, peaceful, surrounded with a nimbus of self-amusement. Unfortunately, they won't let Jack be--fenced-up, heavily trafficked New Mexico has no room for him.

AN UNUSUALLY fine cast supports Douglas. Carroll O'Connor plays a symbolic truck driver, the late Walter Matthau is first-rate as the no-nonsense sheriff on Burns' trail, and the lovely young Gena Rowlands is the woman Jack has to leave behind.

Dalton Trumbo's screenplay sometimes spells it all out too clearly. And then there's the movie's motto: "Do what you want to and the hell with everyone else." That might warm the

libertarian heart, but isn't that the slogan of the spoilers of the West--the oilmen, the ranchers, the Hurwitzes?

Still, there are lines of unmitigated cowboy poetry. Burns tells one assailant that the hot-tempered never prosper: "You'll end up with your belly turned to the sun, your best suit on, and no place to go but hell."

Lonely Are the Brave had a profound influence on Sam Shepard--remember John Malkovich softly describing the film's ending in the PBS version of Shepard's True West? So it's a movie that was important in making our vision of the new West.

Still, Douglas, now 83, is bemused by being frequently remembered as the father of Michael Douglas, and that's how he ends his autobiography.

No doubt Michael Douglas draws some of his intensity from having faced a man like Kirk Douglas across the breakfast table. Despite a bad stroke, Kirk Douglas is still acting and still avid. Kirk Douglas will probably achieve immortality the way Woody Allen described it, not just through the creation of immortal work, but through not dying.

Kirk Douglas appears on Saturday,

Aug. 12, at a tribute dinner, reception, and screening of Lonely Are the Brave at the Wine Country Film Festival. The evening starts at 6:30 p.m. at Valley of the Moon Cinema, Jack London State Park, Glen Ellen. $35 (tribute and film only) or $125. RSVP by Aug. 6. 935-3456.

[ Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

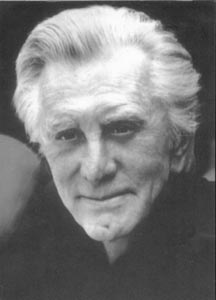

The original gladiator: Kirk Douglas may not don his Spartacus gear for his Aug. 12 appearance at the Wine Country Film Festival, but the doughty cinematic warrior leads the festival's charge into Sonoma County.

The Wine Country Film Festival comes to Sonoma County for its two-week second section, which runs from Aug. 3 to Aug. 13. Films screen at the Sebastiani Theater, Valley of the Moon Cinema, and Roxy Stadium 14. For details, consult the festival's program (available at many local bookstores, including Copperfield's), log on to www.winecountryfilmfest.com, or call 935-3456.

From the August 3-9, 2000 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.