![[Metroactive Arts]](/gifs/art468.gif)

[ Arts Index | North Bay | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

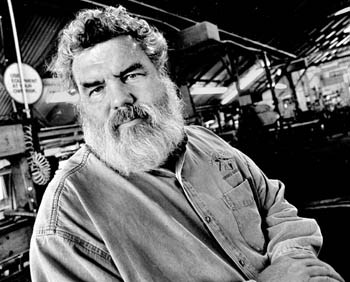

Forging Ahead: Toby Hickman leaves Waylan Smithy after 29 years.

Iron Man

Blacksmith Toby Hickman keeps the anvil and hammer in good use

By Sara Bir

In a world of synthetic hairpieces, cheap newsprint, and junk mail, it can be easy to forget that some people still craft substantial things of lasting value, using principles distilled from centuries of tradition. What's tougher to grasp is that people who roll phyllo dough by hand, weave baskets from white oak they cut themselves, or hit hot iron with a hammer are not anachronisms or reactionaries clinging to fading ways of the past as an act of defiance. They are artists who run businesses completely relevant to modern life.

For proof, look no further than Waylan Smithy and its founder and proprietor of 29 years. Blacksmith Toby Hickman, who had owned the Petaluma forge since 1973, retired in June--but not because he was tired of blacksmithing. "One of the reasons I've sold the business is that I don't get to do it anymore, and I want to do it again," says Hickman, a burly man with a salt-and-pepper beard who surely does look like a blacksmith. "To me, it's the physical act."

Hickman decided to become a blacksmith in 1971. "The standard story is that in the early '70s, I was woodcarving in my garage to hide from my children and I needed tools that I couldn't afford, so I took a class at a local high school to forge tools . . . and I just fell in love with the forge," he recounts.

Before becoming Waylan Smithy, the property--a renovated chicken barn in West Petaluma--was Evolution Art Institute, which was started by Michael Gonzales. Gonzales offered Hickman a space to set up his anvil and forge. "So I set up shop, and shortly after that we got some CETA grants--government educational grants--to teach groups of high school to early college-age [kids] skills in working," Hickman says.

"It bridged me from wanting to be a blacksmith to being a blacksmith," he adds, "from doing the renaissance fairs and kind of eking out a living. From the renaissance fairs I got architectural commissions; from the architectural commissions, I got introduced into my specialty, which is restaurant and commercial interiors with an emphasis on lighting."

Commercial interiors may not be the first thing that springs to a layman's mind when the word "blacksmith" is mentioned, but artfully forged iron creates a striking visual statement. "Forged iron has a texture and a presence that is much richer than any other from of metal," Hickman says. "If you want slick and harsh modern, it doesn't work. We usually go into places where there's mosaics, blown glass, intricate millwork . . . and then we fit right in."

Waylan Smithy has works in San Francisco's Boulevard, Jardiniere, Farallon, and Postrio restaurants, as well as the Martini House in St. Helena, and Manka's Inverness Lodge--all establishments known as much for their impressive interiors as their food. "What I say is, it's my job to keep you happy until the salad gets there.

"Two hundred years ago, probably one person in every 50 was a blacksmith," notes Hickman. "They were working with forge and anvil in 1900. By 1920 the anvil and the forge were full of dust and cobwebs.

"Blacksmithing is undergoing an enormous resurgence," Hickman says. "There are many, many more blacksmiths now than when I started. When we first started blacksmithing, there were a group of us who said, 'If we hang onto this long enough, we're going to go through a renaissance the same way that glass and pottery had.' During the late '90s, everybody that I knew that was any good at this trade was so swamped with work that they couldn't possibly get it all done."

For Waylan Smithy, Hickman didn't have to go out searching for commissions. "I have a marketing philosophy that I should be the last guy you talk to. What I do is extremely expensive, it's extremely labor intensive. There's gas burning, there's steel, there's electricity. These people are all skilled. There's a lot of costs. And so the whole thing ends up being very expensive. There's two big markets for the kind of work that I do: the very rich building their houses, and high-end commercial venues.

"When I started being interested in blacksmithing, there were, across the country, an entire generation of guys--though there's a number of notable women--who came to it on their own and then all of a sudden discovered each other. Most went into artistic blacksmithing, which is the decorative end of the trade."

In the North Bay, Hickman estimates there are between 12 and 15 active blacksmiths. "And each of them tends to have a trade. It's a pretty solid community--it's not small. And rarely do we compete head to head. It used to be when a designer found you they thought you were the only blacksmith alive. In the last several years, the design community has become much more sophisticated about the blacksmithing available."

Hickman does not claim to have a specific style. "I pride myself in being able to work in a number of different styles. I don't know that I have a style any more, other than the fact that I like really to form the metal. I don't want people to know what piece of metal I started with."

Over the years, many blacksmiths have apprenticed with Hickman (a founding member of the California Blacksmith Association and board member of the Artist-Blacksmith's Association of North America for six years) and gone on to strike out on their own, a fact Hickman dismisses as much their doing as his. "It's definitely on-the-job learning and I do show them things, and I have some very good people out there who also show people how to do things. A lot of what we do, you have to build the tools to build the job before you can build the job.

"Often," he continues, "the more time-consuming task is to get something to make the thing rather than to make the thing itself. So not only do I do a lot of training, my staff trains itself." At the time of the interview, Hickman employed four full-time employees and up to three part-time people.

Without Hickman, Waylan Smithy will still retain its name, which came from Mary Stewart's novel The Crystal Cave, part of her cycle retelling the Arthurian legend. "It was told that Wayland the smith made the sword [Excaliber]. In England, on the Salisbury Plains, there's a place called Wayland's Smithy. It was a legend if you left your horse in a pinny, on a rock, you'd come back in the morning and your horse would be shod."

Hickman's retiring hardly means the end of Waylan Smithy; it's just that Hickman won't be its owner anymore. "One of the reasons I'm selling my business is that over the last 10, 12 years, I've developed a very good client base, mostly lighting shops that depend on what I make for their product line," Hickman says. "I don't want them to all of a sudden lose a huge part of their line because I've decided I wanted to do something else." Hickman will keep on blacksmithing, just not on commission. "My plan," he says, "will be when it's done, it's offered for sale.

"Artistic development, business understanding--all that stuff has been an adaptation to allow me to continue to hit hot steel," reflects Hickman. "It's the thing that makes me feel good. It's the feeling of the impact, swinging something heavy and hitting something that yields to that--and yields to it in a way that you intended it to. Just bashing around on hot steel can get to be too much work, but if you actually see something forming under hand, there is an enormous emotional reward.

"I figure somewhere deep in the genetic code of human beings, there is one group that gets some kind of physical reward in the activity."

[ North Bay | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Photograph by Rory McNamara

From the August 1-7, 2002 issue of the North Bay Bohemian.