![[Metroactive Music]](/gifs/music468.gif)

[ Music Index | North Bay | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

Wild Things

Mardi Gras Indians turn up the heat

By Greg Cahill

Forgive Bo Dollis and his cohorts if they slip out of the postconcert parties a tad early, since after an evening of trance-inducing New Orleans R&B and second-line strutting, the Wild Magnolias usually have one thing in mind: sleep!

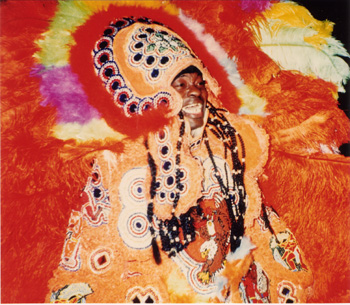

After all, performing onstage in full Mardi Gras Indian regalia--a flashy 100-pound ensemble of feathers, sequins and beads--can exact a toll on a body.

"I think that the trickiest part to performing in costume is that they don't realize the energy exerted while onstage," says Glenn Gaines of the Wild Magnolias, the band's manager and occasional percussionist. He notes that the costumes, with their flowing headdresses and plush plumes, take a year to make, and new ones are made each year. "Yet these suits appear to be weightless when you see the Indians gliding around onstage or in the parades."

North Bay audiences will get a rare opportunity to catch the Wild Magnolias in all their high-energy, funkified and feathered glory when this landmark Crescent City tribe, the first Mardi Gras Indians to put their chants to music, bring their spectacular stage show back to the Mystic Theatre this weekend.

The lineup for the show is Big Chief Bo Dollis, percussionist Geechie Johnson, bassist Nori Naraoka, guitarist Brad Lewis and drummer Doug Belote, as well as costumed Indians Bo Dollis Jr. and Honey Bannister.

For many, the 20 or so Mardi Gras Indian tribes--which rarely perform outside the city--represent the heart and soul of that famous carnival, which has roots that reach far beyond the simple-minded girls-gone-wild debauchery or even the Catholic-oriented Lent connection that often comes to mind.

"The Mardi Gras Indians continue a tradition that pays tribute to Native Americans who befriended runaway slaves and led them to safety," Gaines says.

The first recorded instance of a runaway slave fleeing the plantations to the sprawling bayous surrounding New Orleans, a port city built on the site of a once-thriving Indian village, came in 1725, just six years after the first two shiploads of slaves docked there. In time, slaves received advice from Indians there about living off the land, and eventually constructed renegade bayou communities known as Maroon Camps.

But the Mardi Gras Indian regalia also served a second purpose: for many years, it was illegal for African Americans to march in the city's lavish parade or participate in any Mardi Gras celebration away from the plantation. So blacks formed secret societies within their neighborhoods, donned their Indian costumes and crafted a series of code names, signals and language to mask their defiance. The earliest references to slaves dressed as Indians can be found in 1746. The current crop of Mardi Gras Indians became a powerful symbol of black pride in the racially tense atmosphere of the 1960s.

Big Chief Bo Dollis (who started attending secret Indian meetings as a high school junior and masked for the first time in 1957) made history in 1970 when, at the suggestion of Tulane University student leader Quint Davis, he joined Chief Monk Boudreaux of the Golden Eagles to record the classic single "Handa Wanda."

The tribe helped pave the way for the Wild Tchoupitoulas, which featured Neville Brothers relative Uncle Jolly Landry (who also served as the Wild Magnolias' second Big Chief) and a host of others.

That influence will be celebrated next year with the release of the Wild Magnolias' as-yet-unfinished Funky Disposition, marking Dollis' 50th anniversary and featuring the likes of the Roots, Widespread Panic, Galactic and DJ Logic, among others.

[ North Bay | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Light as a Feather: Hardly. The Magnolias' costumes weigh more than 100 pounds each.

The Wild Magnolias perform Friday, July 30, at the Mystic Theatre, 21 Petaluma Blvd. N., Petaluma. The Bonedrivers open. 8:30pm. $18. 707.765.2121.

From the July 28-August 3, 2004 issue of the North Bay Bohemian.