![[MetroActive Arts]](/gifs/art468.gif)

![[MetroActive Arts]](/gifs/art468.gif)

[ Arts Index | Sonoma County Independent | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

In Defense of Nasty Art

Forget the efforts by the Congress to ban the NEA--how the heck do the rest of us deal with the issue of critiquing nasty art?

By Ann Powers

Everybody has limits, but it's not often that you really get to test one. I stumbled into such a chance late one night sitting at home, reading a comic book. It was the first issue of Grit Bath, a Fantagraphics title for "mature readers," featuring the fractured fairy tales of Renee French. Her stories view transgression through a child's eye: animal dismemberment, booger-eating, masturbation, dead pets, skin-picking, weird sexual encounters in the neighbor's attic.

I was getting a little queasy from all the ripped flesh when I turned the page to find "Fistophobia."

"That one's true," French would tell me later; but authenticity wasn't the point. The point was the strange seductiveness of French's images, chronicling the afternoon a group of kids watch one girl, maybe 11, command another half her age to stick her little fist up the older girl's vagina, as a kind of show. French renders the scene in detail--the incredulousness of the spectators, the beads of sweat on the little girl's brow. And the older girl's genitals, like a cartoon mouth, wrapped around that little one's fist right up to the ruffle of her sleeve.

"Fistophobia" grossed me out, drew me in, made me think.

I had to admit my own attraction to these images, the way the girls stared straight out of the page as if to say: Deal with it. And as I stared at the scene French had so meticulously rendered, I felt myself drawn into emotional territory I hadn't realized was there. I'm not talking about recovered memory, hippie liberation, or good old catharsis. Just the compelling realization that, past the edge of whatever I don't want to think about, there's more.

I'd like to say I wrestled with some demons after my encounter with Grit Bath, but in fact I filed it away in my mind, somewhere between Bataille's Story of the Eye and Dr. Dre's The Chronic. Hey, I'm a macha culture consumer--I've seen Salo, read every Kathy Acker novel, rented every film by David Cronenberg. I've counted the bodies in Menace II Society and fallen asleep to the Wu-Tang Clan. I'm used to being shaken up by art, and I welcome the experience as part of a tradition, one that's perpetually in combat with moralists of both the left and right.

I've always been prepared to stand up for nasty art, whether it's in the gallery or the dancehall. At the same time, I've been searching for a way to critique it--to make distinctions between what's truly transgressive and what's merely gross. Lately, though, the right has been trying to take that critique away from all of us by aggressively attacking anything that threatens to uproot the manicured lawn and dirty the Christianized soul. But authoritarians have always been the enemy of "degenerate" art. What's far more distressing is the unwillingness of progressives to defend it.

The reason for this hesitation is clear: We don't know if we believe in this stuff, and even if we do, we don't know how to deal with it.

Let's remember what the right thinks we're up to. "We are all aware of the Left's cultural agenda," wrote social conservative Samuel Lipman in a 1991 essay for the National Review. "The Left wishes to use culture to remold man and society on radical lines, with destruction of individual autonomy and reason followed by the destruction of every traditional social habit and institution, including churches and ending with the family."

Well, okay. Aside from the bit about the destruction of autonomy (that seems more like a Christian ideal to me), I'm down with it.

For Lipman, every short-haired woman and long-haired man is part of the same conspiracy. But we know there are many lefts, all of which (especially since the '60s) have called themselves new. The movement Lipman demonized is the one I identify with: the transgressive left that means to dismantle those strangling institutions of flag, faith, and family. But there's also a constructive left that shops at Putamayo, drinks herbal tea, listens to Des'ree, and struggles for a better world.

People can pass from one left to the other--I like Des'ree fine. The problem is, values once considered radical have infused mainstream style, while the very people who put those values on the map have reverted to a more moderate agenda. As they've slipped into the same lives their parents had, only with healthier diets, they now feel nearly as threatened by nasty culture as the right does (though for different reasons).

And their apprehension makes the fight to preserve freedom of expression seem hollow.

"The concerns of the left are very traditional," says Ira Silverberg, publisher and editor in chief of High Risk Books and agent for that old troublemaker William S. Burroughs. "They've chosen to fight certain battles, and to avoid others, because they're too dangerous."

Andrea Juno, whose RE/Search Publications have featured many transgressive artists and thinkers, puts it slightly differently: "There's no critique about what's going on. At this moment, the culture's on absolute emergency alert, and people are so deadened."

It's getting harder and harder to find vocal advocates of so-called dangerous art. I think of myriad essays by women music critics examining the clash between their feminist ideals and their love for various forms of hardcore music; Terry Zwigoff's marvelous documentary Crumb, which offered a compassionate analysis of the great comix artist's woman problem; and Greg Burk's recent L.A. Weekly essay on violence in the movies, a pugnacious ode to boiling blood.

But little of this radical spirit has bubbled up to the mainstream. The recent attacks on Time Warner stimulated little more than mutterings about free speech. A few black critics stood up for Death Row Records, an Interscope subsidiary that's home to Dr. Dre, Snoop Doggy Dogg, and other notorious rappers.

Industrial music maestro Trent Reznor of Nine Inch Nails has received even less support. When William Bennett and his unlikely ally, C. DeLores Tucker, dared Time Warner execs to read some of Reznor's lyrics aloud at a meeting, they squeamishly declined. Since then, the few execs who stood up for this music have been negotiating their departures, and Time Warner is looking to sell its interest in Interscope.

Worst of all, the corporation's chairman has backed the very kind of ratings system that progressives within the music business have long opposed. Such dismal events occur, in part, because the people who actually produce and consume the material in question rarely get to present their views in the mass media--kids, especially, are left out of the debate.

"At a certain level, kids become a concept," says Silverberg. "They're not real human people, they're an idea we're protecting."

Kids can't even get in to see Kids, the Larry Clark film that's supposed to speak to the reality of their own lives. Even those arrested-development types who've made a career out of rock and roll or movies (as opposed to cinema) rarely make it onto op-ed pages or chat shows. But if they--if we--did sit face-to-face with Charley Rose, I'm afraid we'd give a tired line.

"Instead of defending the content of their work, they simply deny its impact," right-wing movie monitor Michael Medved has said of the liberal Hollywood establishment.

He's right. All that most defenders of the nasty can muster, especially lately, is an invocation of free speech. Occasionally someone will laud an artwork for its realistic qualities--the "life's disgusting, art must be, too" argument.

This line creates a distance from disturbing art, branding it as a necessary evil that wouldn't exist in a perfect world. Then there's the Barbra Streisand defense: Why don't those bullies on the right pay attention to health care or gun control? Something that matters. Apparently even those who've centered their lives and livelihoods around art don't think it does.

Americans have been encouraged to use art, whether high or low, as a way of getting bad feelings out of our collective system. Hollywood's Depression-era diversions became the psychic peace treaties of the postwar years; we healed our racial divisions through soul music and soothed our conscience about the Holocaust by watching Schindler's List. Songs of protest and social-realist novels and muckraking films offered catharsis, if not a happy ending; we were supposed to walk away with the weight of our disordered thoughts lifted.

Art has worked to help people understand their circumstances and empathize with others. But there's always been that other strain in American art, both high and low, that seeks to undermine the leveling optimism so often used as a whitewash to cover the cracks in the Tom Sawyer fence of our history. Sometimes these expressions have been masterpieces; more often, they're much-loved schlock--Dean R. Koontz novels and death metal. But whether they run deep or just touch the nervy surface, these works share a defiant stance: They say better's not the only --not even the best--way to feel.

Sometimes transgressive art can be constructive. The queercore band Tribe 8 battles sexism by turning revenge fantasies into splatterpunk with songs about castrating "frat pigs." Elsewhere, as in Ron Athey's or Karen Finley's performances, extremism serves an ultimately healing purpose. Athey has made himself into a tattooed-and-pierced, blood-letting freak as a defiant act in the face of a society that would prefer to use his queer, HIV-positive "freakishness" to make him invisible; shoving his unsettling self in our faces, Athey demands acknowledgment and finds peace.

Harder to accept are those artists, many of whom work in the commerce-driven world of popular culture, who don't play by clear political rules. A filmmaker like Gregg Araki, whose queercentric movies celebrate the trashy history of the drive-in and the squishy realities of the body, gets flak from everybody for his gleefully violent and kinky subversions of sexual politics.

And Trent Reznor, who's now cultivating a whole set of Nine Inch Nails proteges on his own label, Nothing, just seems like a cartoon to most people over 25, even though his music is a primary voice of resistance for his fans. (Bill Bennett's favorite NIN song, "Big Man With a Gun," for example, is an anti-authoritarian, anti-cop rant in the tradition of Abbie Hoffman).

The noise he makes, a complicated mix of lush melody and all-out ear abuse, gives shape to the rageful confusion that otherwise just sits in the stomachs of kids with no clear future and no reason to believe. Gangsta rap taps a similar anger--amplified by racism's impact--and even its infuriating misogyny can be a means to comprehend the way oppression turns personal.

What all these artists share is a link to the Romantic-surrealist-dada-punk tradition of art as a bullet in the head of convention, one that, instead of killing, inflicts permanent brain damage. More than so-called victim art or whatever multiculti extravaganzas get booked into BAM or Lincoln Center this year, this is the stuff that forms the aesthetic most threatening to conservatives--and it's what many Americans, especially the young, find most powerful.

What makes it suspect isn't just its sexually explicit, often violent subject matter, but the way it stimulates feelings that frighten and thoughts that don't fit the status quo. This isn't victim art; it's violator art. It intends to mess with you. And it's time to decide what it means to submit.

Art's ability to be vicious goes back farther than even the Sex Pistols. A quick tour of its messy path would include Nietzschean anti-Romantic Dionysian ecstasy; Andre Breton's credo, "beauty is convulsive, or not at all"; Kerouac burning up the road; bebop dusting the big bands; Elvis Presley getting real, real gone for a change; Jimi Hendrix igniting his guitar; Patti Smith channeling Breton quoting Rimbaud invoking Nietzsche heading back toward that old birth of tragedy again.

More recently, mack-daddy auteur Quentin Tarantino has exhumed a violator canon of his own, running on the juice of blaxploitation films, Hong Kong blockbusters, and Martin Scorsese's epic bloodbaths. And so the tradition builds.

It's no coincidence that our whirlwind ends in rock and roll's land of a thousand dances. Ever since the cops busted deejay Alan Freed, this race-mixing, sex-stimulating spiritual art form has been the primary home of, and inspiration for, art's hell-raising spirit. Proudly low in origin but aiming for transcendence, rock demolished the shaky wall between American high and low culture, polluting our most sacred institutions with the chaos of noise.

Could there have been a David Wojnarowicz without the Velvet Underground? Or a Karen Finley without Little Richard?

But in a strange way, rock's legacy--as it was institutionalized by the '60s generation that thinks it owns the motherlode--has become part of the problem. Ask Marilyn Manson, a shock rocker following in the grand gender-bending tradition and a Reznor protege, about those baby boomers and he'll tell you about his dad, who went to Vietnam and killed a bunch of people without knowing why. "If the boomers understand my music, it doesn't make any sense to me," he says. "If it didn't piss them off, would it have any value?"

The 26-year-old Manson's resentment is partly personal, based in the same need to rebel against the father that his own dad probably once felt. But I've heard it expressed by artists and fans who were either born too late to experience the Summer of Love as anything but a burdening shadow, or who lived through it but can't subscribe to the soft-focus liberal vision that was finally distilled from '60s idealism.

A macrame aesthetic is pervasive on the traditional left. "I grew up around that whole another-mother-for-peace thing, and I can tell you those people have no relationship to what is happening in the margins of society," says Silverberg, who is 33. The hippie vibe certainly survives, even among the young. But radical it's not. And the fact that most of the arbiters of taste on the left--as well as the right--still consider that era the key to understanding the transformative nature of popular culture blocks any clear understanding of today's cultural controversies.

The original rock and roll spirit continues to fuel violator art, but it's been shattered and remade by two of its most rebellious children. Hip hop reclaimed rock as an African-American form, rejecting its boomer history but retaining its arrogance and transformative power. And punk, that 20th-century Nietzschean blast beyond good and evil, recast that same history in a cracked mirror, embracing its fury and its power to fragment instead of unify.

In its embrace of punk and hip hop, violator art directly refuses the reconciliation with "values" and liberal optimism that's characterized the shift from the counterculture '60s to the Clinton '90s.

Gregg Araki, who's about to release his most transgressive film yet--the very queer and violent "heterosexual movie" The Doom Generation--describes its plot this way: "It begins with a Nine Inch Nails song and ends with a scene that's like a Nine Inch Nails song. That anger, that nihilism, is totally there in America. Everybody's trying to bottle it and put it on the shelf and pretend it's not there. But there's a huge sense of disenfranchisement and alienation and anger in the world. A lot of the music I listen to is like that, and so is the world I live in. But at the same time, there's a certain hopefulness and exaggerated romanticism in it. It's about the search for love in this world of shit."

The Doom Generation is part of a growing subgenre of teen movies that updates the juvenile delinquent tradition by gagging the didactic voice of authority.

One function of violator art is to present a mirror reality, in which the standards of society are "totally fucked up" (to quote the title of an earlier Araki film), the power structures toppled, the margins made central.

"What punk and metal were about was kicking a hole in the world," says Manson. There's something at the bottom of that hole: all the aggression kids' parents train them not to feel, the fears and desires that fill them even if they try to be "good."

Maybe those longings are for a better reality, or maybe they're for something more base, like the chance to kill that kid who tormented you all through fifth grade, to beat him bloody, as the class wimp does with his metal lunch box in Marilyn Manson's best song. Either way, what the fantasy offers is a chance to act out your own submerged selves--not to get rid of them, but to face them down.

In gangsta rap, the menace that can't be tamed is not only the righteous anger of young black men but anyone's lust for mastery in the face of the unpredictable. "Everything has to do with the word stay," says Dat Nigga Daz, a cousin and collaborator of Snoop Doggy Dogg and one half of the duo Tha Dogg Pound, the latest Death Row/Interscope act to get the fish eye from Time Warner. "Stay your ass out of trouble, stay out of jail, stay out the ground; in Long Beach you stay busy, you have something to occupy your mind. Because if you ain't doing something, you'll go out and do something."

Daz's statement evokes the tricky strategies of ghetto life, but that much touted "realness" isn't what attracts most listeners to gangsta rap; it's the skill of the artifice, the way it molds the tension of ordinary experience into open-ended narratives.

The viciousness that matters lives in this music's beats and rhymes. The artist's reputation may add to the listener's fantasy of what Henry Louis Gates Jr. has called "the Scary Negro, in its 1995 edition."

But the artful gangsta rapper manipulates that common nightmare, setting up a symbolic confrontation between the rapper and the listener. "What would you do, if you could mess with me and my crew?" Tha Dogg Pound taunt in their first hit, from the Natural Born Killers soundtrack. A typical Long Beach slowgroove simmers in the background; the singsong phrase repeats, a question hanging smoky in the air. It pops up again between elaborate boasts by Daz and his partner Kurupt about exactly what evil things they'd do if you stepped to them, and although guest vocalist Snoop cuts it off with a quick dismissal in the chorus, that question is what lingers after the song is over.

What would you do?

The offenses of hardcore rap, its florid references to violence and sexual degradation, offer a cheap, sick thrill, but the reason this music has captured so many listeners isn't its simple misogyny or brutishness. It's the way the graceful tease of those funk beats mixes with lyrics that confront or even repulse. In many ways, this music works like pornography; when it's half-baked, it's uninteresting and depressing, but when it's artful, it can get you thinking about things you'd never do in your waking life--things you base your waking life around not doing.

My friend Natasha Stovall has this fantasy about DJ Quik, in which she plays around with the different roles in his songs. I can get into it, imagining myself as a 'ho, distilling the game of sex to a Salome's dance, each lifted veil offering further arousal and mortal danger. Or as a mack, with the power to sell myself instead of being sold. Or, when the game gets cruder, as that pussy taking the force of a giant dick. (Tell me you haven't had that fantasy in some sleepy hour, whatever your sexual persuasion). Or as the dick sticking it in.

Every pop song offers this same fluid mix of identities, as the loose frame of the music makes room for the listener to move around. In hardcore hip hop, that movement is always a dare. It's theatrical, sometimes comical, as in the work of Staten Island rapper Ol' Dirty Bastard, who mixes impossibly obscene jokes with a slurry, "insane" delivery in an embodiment of hip hop's reckless id.

Sometimes it's as rule-bound as sadomasochism, as in the cinematic scenarios of Ol' Dirty's posse, the Wu-Tang Clan. Performers and listeners can forget that this is fantasy and take the game too far into the real world. But that can happen with anything: with John Hinckley and Jodie Foster, or David Koresh and the Book of Revelation.

But a kid like Daz, who knows he's an artist, isn't casual about extremity. He's mastering it. He'd probably agree with French when she says, "Sometimes to get to the feeling you want, you have to go overboard, and it leaves an aftertaste."

The ugly image, the drawl of a young man saying beeyatch, or the nails-on-chalkboard sound of a loud guitar: All these devices work as a mind-clearer, fighting against what art critic Robert Hughes (who defends Robert Crumb but sneers at Reznor) has called the "culture of therapeutics." This notion that even transgressive art must enrich and heal dominates the American aesthetic; it's the justification for the artist's arrogant act. We know how the culture of uplift shapes moral conservatives' views, but we're less likely to acknowledge its influence on the rest of us.

A typical champion of Bill T. Jones, for example, would emphasize his ultimately hopeful message, and not mention the possibility that Jones might want his audience to be repulsed by the dying people he sometimes brings onstage. After all, living with AIDS makes for plenty of repulsive moments.

Maybe Jones is pissed off. Maybe he wants to shove that ugliness right in our faces and say, deal with it.

This is where the argument that violator art causes violent behavior begins to fall apart--what its critics don't understand is that fans of this material aren't made any more comfortable by it than its enemies. But they know how to use the experience of being bothered; it's a chance to meet the source of their own pain, their aggression, their hate.

Violator art begins with the premise that these negative feelings belong to us all, and that we can't be cured of them.

"It has to do with exercising--not exorcising--those feelings," says French. "Maybe you need just to feel it sometimes." My boyfriend and I recently spent a trashy evening at home with a few cult videos. We rented an early David Cronenberg [his film-school project] and a low-budget exploitation flick called Hollywood Boulevard.

The Cronenberg was a hopeless rip-off of Butnuel in his priest-and-cow phase, with none of the unsparing insight into sexual anxiety that would later make Cronenberg a great violator artist. But his weak effort only disappointed, while Hollywood Boulevard truly sickened me. What I hated most was that the movie's heroine kept getting raped, again and again, in scenes meant to be an amusing send-up of exploitation's bodice-ripping reflex.

How could I, who relished every cringe-worthy detail about those twin doctors and their womb-torture instruments in Dead Ringers, be outraged by a C-movie's tame rape-scene rip-offs? I think it's because Hollywood Boulevard didn't go far enough. What I mean is that the film used distancing techniques: cheap jokes, irony, and the classic she-really-likes-it disclaimer--when I finally left the room for good, the heroine was just beginning to get into her third rape--to help viewers avoid confronting what rape might actually feel like for victim and perpetrator.

Nor did the film require me to think about what I was watching--in fact, thinking about it made me want to turn it off. Dead Ringers shattered distance, implicating me. Hollywood Boulevard let me off the hook. Not all art that claims to be transgressive is worth caring about. But you can't tell the bullshit from the real by setting moral standards. You have to set artistic ones.

And that means being honest about your responses. Plenty of times you won't know what to think--I sure don't, but what I'm trying to do now is keep thinking. Not turn away from what's inside, when it creeps out at the beckoning of something I ought to hate.

"If it disturbs me, I go forward with it," French says of her creative process.

That's what we need to do, too. Deal with it.

[ Sonoma County Independent | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

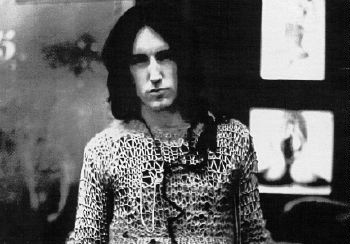

Pitched Trent: Time Warner execs squeamishly declined to read Nine Inch Nails' lyrics penned by the volatile Trent Reznor. Baby Busted: Shock-rocker Marilyn Manson doesn't want to appeal to Baby Boomer fantasies of peace-loving rock 'n roll.

Baby Busted: Shock-rocker Marilyn Manson doesn't want to appeal to Baby Boomer fantasies of peace-loving rock 'n roll.

Web exclusive to the July 24-30, 1997 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.