![[MetroActive Movies]](/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | Show Times | Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Stranger than Fiction

Against all odds, today's documentary filmmakers are keeping it real

By David Templeton

ALBERT MAYSLES shakes his white-topped head, forces out a gust of bemused laughter, and leans in close to his interviewer. All the while, his sparklingly clear eyes make direct and inescapable contact.

He's been talking about Salesman, a hard-hitting, near-legendary documentary about door-to-door Bible peddlers that was filmed in the mid-'60s when Maysles, now 72, was 39. Now, sitting "backstage" between films at the Double Take Film Festival, an annual North Carolina event devoted to documentary films, the New York-based filmmaker--surrounded by a respectful crowd of fans--has just been informed that the film in question was once seen on the long-lived and much-lauded PBS documentary showcase called POV.

"So you saw it on POV, did you?" says Maysles, his lips curling into a knowing smile. "Well, it took only 25 years to get it there."

He then tells of his countless efforts to persuade that venerable program--for years one of the very few such venues that existed for documentary films (and, with the promise of $500 per minute of film, still one of the better-paying gigs)--that Salesman was deserving of the public's attention.

"Whenever I'd hear there was a new program director, I'd try again," he says. "On one occasion I called a guy up and he says, 'Oh, I've heard of your films. I'd love to see it.' So the guy comes over to the studio, and halfway through Salesman, when I come in to change the reel, I see that he's been crying. He's been sobbing.

"And I think to myself, 'Oh my God! At long last I'm gonna get this film shown,'" Maysles says with a grin. "But the guy says, 'Don't bother changing the reel. I don't need to see any more. This is too depressing. My father was a door-to-door salesman.' So he passed," Maysles sighs. "Such is the life of a documentary maker."

IT WOULD SEEM from listening to Maysles' woeful tales (and he's got scads of them) that such a life--specifically that of an independent documentary maker--is one of extraordinary uncertainty, a rough existence alternating mainly between days of rejection, days of frustration, and days of disappointment.

What sets it apart from the life of other independent filmmakers--people like Quentin Tarantino and Kevin Smith, dedicated to the making of fictional films--is that the Tarantinos and the Smiths hold at least a slim chance of attaining financial success. There are no independent documentarians in the "rich filmmakers" club, because documentaries, at this point, almost never make it to the mainstream.

This, in spite of the fact that many observers agree that the best films to come out of the independent scene of late are the documentaries, many of them brilliant and dazzling works of art that touch the emotions and jolt the senses--yet still make no money.

"Oh, it's a crazy life," Maysles affirms, with an amiable chuckle. "But it's also a very rich life, a life very much worth living--if you happen to have what it takes."

This notion of documentary as a noble-yet-underappreciated art form is, understandably, a very hot topic at the Double Take Film Festival, one of the few film fests in the country that is devoted entirely to documentary films. Held annually in the town of Durham--where the towering smokestacks of the tobacco industry rise above the downtown cityscape--this relatively new festival is co-sponsored by Duke University's Center for Documentary Studies and is quickly gaining a reputation as a kind of documentary-makers' Sundance.

It's an unpretentious, quirky event that offers a comfy combination of polished showmanship and aw-shucks affability, the kind of festival at which the town's beaming mayor shares the stage on opening night with world-class filmmakers.

"Documentary is important," the mayor explains to the cheering crowd, "because it reminds us that there is real life out there somewhere." Indeed.

Under the direction of Nancy Buirski, Double Take boasts some serious Hollywood-style star power on its impressive board of directors, including Jonathan Demme, Ken Burns, Barbara Kopple, John Sayles, Lee Grant, Martin Sheen--and even Martin Scorsese, who, unable to attend this year, sent instead a giddy, pre-filmed greeting that was screened during the opening-night festivities.

Like camera-toting pilgrims arriving in documentary Mecca, grateful aficionados swarm each April to Durham's quaint downtown, which is permeated with occasional wafts of menthol from the surrounding tobacco factories. The hallways and courtyards of the 100-year-old Carolina Theater echo with shop talk as this mingling mass of doc-makers, most of them a bit giddy under the rush of so much mutual appreciation, openly enjoy a rare opportunity to compare battle scars, share success stories--and watch hours and hours of documentaries. These films include offerings from around the world, by relatively new filmmakers such as Jessica Yu (Breathing Lessons, The Living Museum) and Liz Garbus (The Farm: Angola, last year's Audience Appreciation winner), as well as legends like D. A. Pennebaker, Errol Morris, Lee Grant, and Albert Maysles.

BEYOND DURHAM, however, the art of documentary is still fighting for an audience. As Maysles' POV story illustrates, the cinematic traits that are counted as strong points in fictional films--namely, realism and strong emotion--are often the very traits that are counted as liabilities when a documentary is called unfit for mass consumption.

It's nothing new. Over the course of his long professional career, Maysles, who has rubbed shoulders and shouldered cameras with the industry's most inventive and pioneering practitioners, has made dozens of documentaries, including several that are certified classics, such as Gimme Shelter (the 1970 film of the notorious 1969 Rolling Stones concert that climaxed with the onscreen murder of a concertgoer at Altamont Speedway) and The Beatles: The First U.S. Visit (the day-by-day cinematic chronicle of the Fab Four's historic 1964 American debut)--both co-directed with his brother David.

But in spite of his status as a living legend, Maysles has fought hard for every penny (and every shred of critical respect) that he has earned. Not that he's earned many pennies; he long ago took to making commercials on the side, just to stay alive. It's a tactic most of his peers resort to at one time or another.

"Documentary," asserts Marina Goldovskaya, director of UCLA's documentary film department, "is the shortest road to poverty."

Also a documentarian, originally in her homeland of Russia, Goldovskaya (The House on Arbat Street) often warns her students about the pitfalls that await the committed documentarian. She can recite the life stories of countless documentarians, along with all the grisly details.

"Robert Flaherty," Goldovskaya illustrates, "had many successes, but even more failures. He made wonderful films that no one ever saw."

The Big Picture: Critics consider 'Nanook of the North' to be the most influential documentary ever made.

Flaherty was the camera-toting adventurer whose groundbreaking 1922 film Nanook of The North--the first full-length documentary--is believed by many to be the greatest documentary ever made.

But in the end, Goldovskaya says, Flaherty died of a broken heart.

Even so, Goldovskaya is as dedicated to documentary as Flaherty was. "I would never, never, never change my orientation," she insists. "Never. Yes, I could make fiction films instead. I never wanted to, and I still don't."

The logical question, of course,is why?

First of all, it's nearly impossible to find anyone willing to underwrite an independent documentary; it took Leon Gast 23 years to raise the money he needed to complete his 1996 documentary When We Were Kings (about the 1974 heavyweight championship bout in Zaire), which went on to win an Academy Award and a miraculous distribution deal that placed it in mainstream theaters throughout the country.

Which points to another problem. It's almost unheard of for any multiplex theater to exhibit a documentary film; such box-office successes as Kings and Michael Moore's Roger and Me are the rarest of exceptions (another being the grueling chronicle Everest--shown only in giant-screened Imax theaters--which currently boasts a domestic box-office take of $68 million and counting).

Some documentarians are lucky enough to see their work distributed to America's smaller "art house" theaters--where the word "blockbuster" is given to any film bringing in more than a million dollars or two in earnings--yet most documentaries never get beyond a few screenings in film festivals, if that. Many reality-based filmmakers have had to turn to television, a proud sponsor for documentary films in the early days of the medium. Even though premium stations like HBO and Showtime--along with cable channels such as Lifetime, A&E, the Learning Channel, and of course PBS and its POV program--have been actively producing and promoting some first-rate documentaries, they've been simultaneously polluting their own waters with such dreck as HBO's documentary-esque Pimps Up--Hos Down and Cab Driver Confessions (programs that represent the influence of such "reality TV" shows as Cops).

All told, there's little room at all left for the highly personal, occasionally disturbing subject matter that has inspired some of documentary's greatest masterpieces.

"It's brutal," declares Dean Wetherell, a young documentarian from New York. He and his filmmaking partner, Lisa Gossels, have recently begun the exhausting, time-consuming film festival circuits, accompanying their marvelous film The Children of Chabannes (a popular success at Double Take, by the way).

"Making a documentary film is like running the Iron Man Triathlon blindfolded with no water stations along the way," Wetherell says. "You're running a race with absolutely no support. And it might be getting worse."

IT'S ALREADY GOTTEN so bad, in fact, that many longtime documentarians are quitting the field altogether. Laurel Chiten caused a small sensation with her film The Jew in the Lotus, the tale of a troubled Jewish man whose faith is rekindled after meeting the Dalai Lama; in spite of her critical kudos, Chiten would have starved waiting for any financial rewards. Realizing that good reviews can't pay for food and rent, she quit making documentaries. Ruth Ozeki, whose work includes numerous documentary series and the award-winning Halving the Bones (the story of Ozeki's mother and grandmother), has thrown in the non-fiction towel as well.

"I finally realized that the life of the documentarian was not a very sustainable one," Ozeki says.

After putting $30,000 worth of debt on a credit card to make Bones, and failing to land a distributor (or make that all-important sale to POV), she's made a much bigger (and more lucrative) splash as a best-selling novelist. My Year of Meats is her first novel; ironically, it's a comic satire about a beleaguered crew of documentarians traipsing across the American Midwest in search of the next great shot. Ozeki, having finally left the documentarian's hard-scrabble life behind--and having finally pulled herself out of debt--insists she's never looked back.

Adding further insult to injury: In recent months, the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences--the people who hand out the Oscars--has dealt a blow to the art form by eliminating the distinctions of "documentary short subject" and "feature-length documentary" from its list of categories. In the past, one Academy Award was awarded in each category. But starting in the year 2000, a single award will be presented for Best Documentary, effectively cutting in half the number of documentarians who will get a shot at standing in the Oscars' career-boosting spotlight.

"Documentary is kind of the poor stepchild of the film world," agrees Ed Carter, chief archivist at the academy's 5-year-old documentary film archive in Los Angeles. "It's a shame that so many of the great documentaries are never even seen anymore."

And yet, according to Goldovskaya, even in the face of so many obstacles, student interest in documentary is at an all-time high, with record numbers of would-be filmmakers entering her classes with dreams of becoming the next Albert Maysles, Robert Flaherty, or Marina Goldovskaya--in spite of her dire warnings about broken hearts and that "short road to poverty."

So again, the question is: why? Why flirt with poverty when there's often better money and more respect to be gained from, say, flipping burgers at McDonald's?

One answer lies in the fact that, for some filmmakers, critical success is enough. And many critics, including Roger Ebert and Janet Maslin, are fierce champions of documentary.

"Documentary is an extremely creative art form," explains international film critic David Thomson, "and it makes for some very provocative, stimulating, entertaining films.

"Not to say that documentary is purer or nobler than fiction," he adds. "There are plenty of dull, bad, pretentious, and prejudiced documentaries, just as there are plenty of bad feature films. But it seems to me that documentary is a form that offers endless artistic choices to a filmmaker.

"It's a very rich medium."

IN MY CASE," says D. A. Pennebaker, "asking why is like asking the guy who carves the Lord's Prayer on the head of a pin why he does it. There may be more expansive ways of dealing with his art, but it's all he knows how to do. Documentary," he says with a shrug, "is all I know how to do."

At 74, Pennebaker, another living legend among documentarians, is still going strong. In fact, with his close-cropped hair, broad shoulders, and powerfully proportions, Pennebaker looks like someone you wouldn't want to have to fight. And Pennebaker is a fighter, having carved out an impressive career despite the requisite setbacks.

His films include 1967's Bob Dylan concert film Don't Look Back and 1969's Monterey Pop, as well as the groundbreaking 1960 political romp Primary and 1993's Oscar-nominated Clinton campaign chronicle The War Room, co-directed by Pennebaker's wife, Chris Hegedus. Pennebaker was a founding member of the pioneering Filmmakers Collective, which formed in the early '60s. An energetic gang of idealistic young artists that also included Albert and David Maysles, the collective is widely credited with Americanizing the French notion of cinéma verité, with its live action, hand-held cameras, and mandate of objective observation.

During one of Double Takes' midmorning panel discussions--this one on the "great documentaries of the 20th century"--Pennebaker gently prods the crowd's film-festival optimism when he reminds them, "Documentary is a hazardous career. And my advice to those of you who are just starting out is, 'Go back. Stop, before it's too late.'

"You won't, though," he allows. "You'll do what you have to do. And if you can do it, and bring it off--and make a career for yourself--you'll find it's an amazing way to live your life."

This warning--which comes across as both a threat and an invitation--is revealing as it demonstrates a bit of the weird love-hate, manic-depressive mindset that seems to operate at the heart of the modern documentary movement.

INDEED, for most of the filmmakers here this weekend, documentary is a movement. To those in the rowdy trenches of true-life filmmaking, it's a Holy Grail-like quest for cinematic purity and truth; a close-up, in-your-face examination of the real world, warts included; a thrilling, terrifying epic adventure in which knights with cameras try valiantly to capture wonderfully magical moments that are, for the most part, entirely outside their control.

"Making a documentary is like escaping from the coal mines and finding yourself skiing out on the slopes," says actress/director Lee Grant. "With documentary, you're free, you're making a journey, you're going someplace you've never been before."

A two-time Oscar winner (in 1975, for Best Supporting Actress in Shampoo, and then in 1986, as the director of the Best Feature-Length Documentary, Down and out in America), Grant has made numerous non-fiction films over the last two decades, films that have taken her into prisons and hospitals, over picket lines, inside homeless encampments and violent courtrooms, and onto some very mean streets.

"You get to kick open doors that are risky, and you ask people questions and sit there amazed as they let you into their houses and lives, and tell you their most personal stories," she says. "It's a very privileged place to be."

Slawomir Grunberg, a Polish-born cinematographer and award-winning documentarian, sees his vocation as nothing less than a holy war; it's the battle of truth vs. illusion. "I don't like fictional films," Grumberg softly admits, sipping a coffee after a screening of his own film, School Prayer: A Community at War. "I believe that real life is much more interesting."

Grumberg's unassuming presence might prove especially inspiring to the colleagues and eavesdroppers who hear him proudly announce that School Prayer has just been accepted by POV, proving, at 500 bucks per minute, that the occasional pot beneath the documentary rainbow truly does exist.

And there are some in the industry who see other signs of hope.

"In spite of everything, this is probably the best time for documentaries in a long, long while," insists Nancy Buirski, the festival's tireless director. "In the last 10 years, there's been a kind of documentary renaissance, mainly because of the cable stations requiring so much documentary 'product.' The positive result for a festival like this is that there's a huge audience watching TV and getting its appetite whetted for documentaries. So I think the anti-documentary stigma will be declining more and more."

ON THE LAST DAY of the festival, the sky over Durham is overcast and stormy, and the overall temperament of the revelers has down-shifted into a softer, somewhat melancholic mood.

Out in the courtyard, an authentic North Carolina barbecue is served, and a distinctively quirky awards presentation is taking place, with Buirski standing on a chair to shout out the names of the festival winners, while the crowd encircles her, cheering as each recipient steps forward.

Albert Maysles, stopping to chat with friends before trotting back to New York--and the harsh realities of the real world--offers a final piece of wisdom. "This is what Spinoza said," he says with a smile. "'All things excellent are difficult and rare.' Well, that's documentary. Difficult and rare.

"Maybe someday the rest of the world will see it our way."

[ Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

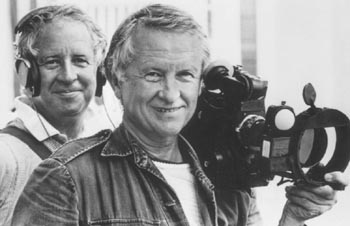

Point of view: Filmmaker Albert Maysles overcame countless rejections of his provocative work to become a living legend, but the 72-year-old director still wonders whether documentaries will ever get the respect they deserve.

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

Reel life: Lee Grant, right, has directed several acclaimed documentaries.

From the July 22-28, 1999 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.