![[Metroactive Dining]](/gifs/dining468.gif)

[ Dining Index | North Bay | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

Fresh Choice

Cafe Japan gets it right

By Maria Wood

My sister had a three-year-old neighbor in Los Angeles who would always tell her, "I love strawberries." So one day, she picked the freshest, plumpest fruit from her strawberry patch and brought it over to him. He tasted one and wrinkled up his little nose. "Strawberries don't taste like that," he informed her. He then ran over to his cupboard, pulled out a jar of Smucker's jam, and announced "These are the yummy strawberries."

Me, I love Japanese food. So you can well imagine my surprise when I discovered that, after all these years, I was eating Smucker's-style Japanese cuisine.

When I first went to the newly opened Jenn and Yo's Cafe Japan in downtown Santa Rosa, the food tasted a bit off, like it was missing something. It was. It's missing the monosodium glutamate. Unlike most other Japanese restaurants, Cafe Japan uses no MSG. Plus, the food is almost exclusively organic. Needless to say, it takes a little getting used to. It's like eating corn-syrup-laden jam all your life and then being confronted by a fresh, ripe strawberry. What to make of this subtle flavor? Luckily, living in Northern California has taught me a thing or two about giving real food a chance. It always pays off. And this was no exception.

Take, for example, the humble inari, a bean-curd pocket stuffed with rice. Like vanilla ice cream, inari is a straightforward food that serves as a good gauge of the quality you're getting. And Cafe Japan serves some of the best (if not the best) inari I've ever had ($3.50 for two).

Typically, restaurants use ready-made pockets that are already fried and seasoned with MSG, oil, and sugar. At Cafe Japan, 35-year-old chef and co-owner Yosuke Saito uses organic tofu and seasons it with a mixture he prepares of mushroom stock, kelp stock, organic sugar, soy sauce, and a sweet, cooking sake. He then fries it and stuffs it with organic rice.

Now, on to the fish. Sushi is not raw fish on rice. Sushi is an art form.

In his native Japan, it takes about five years of training before one can be considered a sushi chef, says Saito, who apprenticed at the Asahi Sushi restaurant in Kesennuma city. After moving to California in 1994, he worked at the Samurai Restaurant in Mill Valley and, most recently, at JoJo Restaurant and Sushi Bar in Santa Rosa.

"In Japan, you have to earn your uniform little by little," he says. "After a couple of years, you are allowed to wear this," he adds, pulling at his shirt, "but the pants must remain usual." After a couple more years, the trainee is allowed another piece of the ensemble. "At the very end, you can wear the entire uniform, and it is a very big honor," Saito says. His brother Junpei, who was trained at the Miyagi Chorishi Senmongakko culinary school, came to Santa Rosa last month so that he too could work at the new restaurant.

There are only a handful of Japanese restaurants in Sonoma County where the chefs were actually trained in Japan, and it seems that some of the traditional techniques that took generations to perfect are being lost. For example, the albacore tuna sushi at Cafe Japan is outstanding ($4 for two), partly because Saito takes the added step of searing the fish so that it retains its natural juices. He was taught that each type of fish needs to be treated differently: red tuna is seared with soy sauce; halibut is salted and marinated overnight with sea kelp; shrimp is marinated in sweet vinegar. And, of course, everything needs to be sliced with precision at the right angle.

Even the little tricks of the trade make a big difference. I don't know how many times I've pulled off hunks of sushi rice from under the fish so that I could get a better balance between the two. "In Japan, you learn to make a little air pocket inside [the rice ball] so that it's firm on the outside but soft when you bite into it," Saito says. "And that way, you also don't use as much rice."

Not only is Saito trained in Japanese cuisine, he also makes a mean American-style barbecue. He learned the proper techniques when he was a youngster and an American family moved in next door. "Our families couldn't speak together well, but we could eat together very well."

As a teenager, Saito visited relatives in Marin and decided there was a lot more to California than just barbecues. Twelve years later, he moved to Mill Valley and started working at Samurai Restaurant. Just before the company Christmas party, Saito and Jennifer Bessette, one of the waitresses there, were asked to help provide the entertainment.

Saito plays guitar and has the broad smile and laid-back manner of a California musician. Although I haven't heard it, I'm sure he uses the word "dude." On the other hand, Bessette has a certain tentative giggle and other mannerisms that I've noticed in many Japanese women. Yet she's also quite the rocker and sang lead vocals and played rhythm guitar for the local band Bella Luna. When she was 22, Bessette, now 33, came out to California from the East Coast on a Greyhound bus, bringing along little else besides a guitar, an amplifier, and hopes of becoming a rock star. In the meantime, she waited tables to pay the rent.

Bessette always insisted on working at Japanese restaurants. That way, she could satiate her other passion: sushi. "I can't say I liked sushi much the first time I tried it. I was a little scared of it," she says with a giggle. But after that initial attempt, she tried sushi again. And again. "And I became addicted to it," she says. She'd drive from New Hampshire to Boston specifically for sushi. "I spent all my spare money on it," she adds.

Soon she started waitressing at Japanese restaurants. She spent six months in Japan. She took eight semesters of Japanese language classes at a couple of different colleges. "I think about 10 percent of my brain is Japanese by now," Bessette says.

So while barbecue helped lure Saito to Marin, sushi helped hook Bessette into the restaurant. Then, before the Christmas party, the two got together to create a Japanese rendition of "Please Mr. Postman." They practiced each night and got to know each other. Six months later, they married.

Right around the time they were discovering each other, they discovered the Whole Foods Market across the street from the restaurant and started eating the organic produce there.

Saito says his own emphasis on organic cooking can be attributed as much to Northern California culture as to his training. "Luckily, around here, wherever you look, there's great organic produce," he says. "And once you taste it, you can't go back."

Little by little, Saito and Bessette began talking about opening their own restaurant and using all those tasty, organic ingredients and throwing away the MSG. And Cafe Japan was born.

If there's any fault with the restaurant, it's that Saito and Bessette are so true to their vision. I couldn't get my customary dessert of green tea ice cream because they haven't found any that doesn't contain artificial coloring. They'll probably make their own once they settle into a routine with the new business. But until then, I'll just have to fill up on extra albacore.

[ North Bay | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

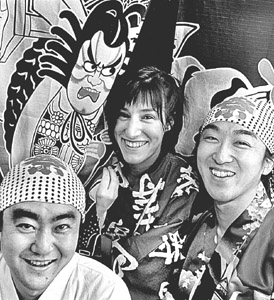

On a Roll: From left: Yosuke Saito, Jennifer Bessette, and Junpei Saito find the love, lose the MSG.

On a Roll: From left: Yosuke Saito, Jennifer Bessette, and Junpei Saito find the love, lose the MSG.

Jenn and Yo's Cafe Japan is at 98 Old Courthouse Square in Santa Rosa (near 4th and Mendocino). Open Tuesday through Saturday. Lunch, 11:30am-2:30pm; dinner, 5-9pm. Lunch special, $10. Entrées range from $9-$14. 707.566.7650.

From the July 11-17, 2002 issue of the North Bay Bohemian.