![[Metroactive Dining]](/gifs/dining468.gif)

[ Dining Index | North Bay | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

Once More, with Relish

Slow Food energizes communities, one table at a time

By Heather L. Seggel

One day last summer, I was riding through Healdsburg with my father on one of our occasional thrift store junkets. The road was wavy with heat, and the car's black interior was acting as a solar oven, trumping the air conditioner and melting our brains. My dad made a U-turn so abrupt I jumped, then pulled into the shade of what looked like an abandoned produce stand. "Look at that," he said.

I looked and saw more tomatoes than I've ever seen in my life.

Wheelbarrows full of tomatoes, boxes full to overflowing, and row upon row of plants. They were a mess of leafy green at first glance, then suddenly I could glimpse the red, gold, and green fruits peeking out seemingly everywhere. We got out, hoping to find someone, and looked around for five minutes or so. Nobody came, so we picked up four bulging, red heirloom tomatoes so full of juice they threatened to explode before we could set them in the car. We folded up a few dollars and stuck them in a six-pack cooler that was under the funky folding table out front, and left, jokingly watching for police or pitchfork-wielding farmers in the rearview mirror.

The tomatoes. Each one big enough to make a meal, juicy enough to sauce a pound of pasta, as delicate as angel food yet substantial as a steak at the same time. The tiniest dash of salt brought out sweet and acid notes, and a stale baguette drank up the juice and became extraordinary. It was a perfect meal--almost no ingredients, just pure flavor, feeding more than simple hunger.

I didn't know it at the time, but I was experiencing a slow food moment.

"Those moments can be very nourishing," said Barbara Bowman. "You took the time to find something wonderful from the earth that someone specialized in growing and that was really delicious and enjoyable."

As leader of Slow Food's Healdsburg convivium, or chapter, and head of Sonoma County's Ark USA committee, which works to protect endangered regional specialties from culinary extinction, Bowman takes deliciousness seriously. It's a significant part of the Slow Food movement, in fact. Even their manifesto extols the virtues of "suitable doses of guaranteed sensual pleasure and slow, long-lasting enjoyment." Who could resist?

"It's more than just getting together and eating well," cautioned Bowman. She's right, of course. Slow Food members educate themselves in great detail about the foods they advocate, and the Ark in particular calls for detail-oriented activism and commitment. But when all those things culminate in getting together with friends and pigging out on freshly made organic ice cream, it's easy to see why more people continue to join and how the movement has grown globally by keeping a local focus and delighting the palates of all involved.

Raiding the Lost Ark

The Slow Food movement started in Italy in 1986, as journalist Carlo Petrini's inspired response to a McDonald's opening near Rome's landmark Spanish Steps. Petrini conceived of the movement (and its mascot, the snail) as both a reaction to and rejection of the encroaching fast-food aesthetic. Rather than identical restaurants throwing together tasteless food for customers to scarf down, Slow Food emphasizes the pleasures of dining on real food in good company at a leisurely pace. Members bring folks to their table, and as word spreads their numbers multiply.

In the last 15 years, that expansion has carried Slow Food to 50 countries worldwide, boasting more than 70,000 hungry members. Slow Food USA has been gaining strength since the early 1990s, with official headquarters opening in New York just two years ago. The United States now has roughly 7,000 members divided among 60-plus convivia (the name comes from Latin for "feast") and counting. U.S. membership is largely concentrated in the northeastern United States and here in foodie California, where the North Bay alone plays host to five convivia. Interest is also growing in the Midwest and South, which may help the agricultural economies in those areas. Almost any community with a decent farmers market and a healthy curiosity about where its food comes from is ripe for conversion--and is bound to have a good time in the process.

Among the activities various convivia have staged are tours and tastings at community dairies and chocolatiers; a study of honey making complete with an on-site hive, honey, and cheese tasting; and a presentation by a brewer on the finer points of mead making. Events generally contain a teaching segment followed by a tasting, so participants get a feel for how their foods come to be. Sometimes the education occurs more spontaneously and comes with a side of enlightenment.

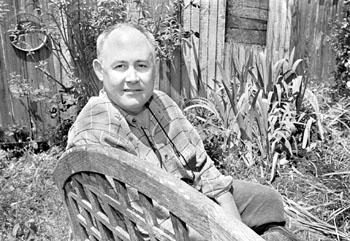

Slow Food Russian River founder Michael Dimock described an event he participated in a year ago. Friends trapped and fattened a wild boar, and on the day of the event it was slaughtered and prepared with homemade, fresh-from-the-trees applesauce. "We cooked all day," he said, with about 50 people pitching in. They all ate together at a long table set outside and shared some "terrific" wine. "It was a transcendent moment," said Dimock. He said the food was exceptional but that it wasn't the sole source of nourishment, adding, "I'm fed deeply by [Slow Food's] actions, and by participation with the people involved."

This hands-on approach gives another spin to the idea of slow food: It's not just the opposite of fast food; it's part of a tradition and the product of loving preparation, often on a very small scale. These are the qualities Slow Food members are out to preserve, and the foods that live up to them find a special place in members' hearts and--if they qualify--on the Ark.

Obscure regional delicacies and "endangered" foods may be saved by the Slow Food movement's Ark of Taste project. Like its Biblical namesake, the Ark is an attempt to save foods that could slip from our midst, and carry them on into the future. Any Slow Food member can nominate a food item, which then has to meet rigorous criteria before a committee will even sample it, let alone consider it for inclusion. The presence of genetically modified raw materials or transgenic breeding will automatically disqualify an item from the Ark, just as Noah would most likely have sent Dolly the sheep packing come flood time. The food also needs to satisfy the bottom line and exhibit some sales potential. Bowman said the committee looks for foods to be "commercially viable, to have more potential in the marketplace than they're enjoying now." If it makes the cut, the group will work to create a sustainable market for the product so it can thrive.

The most recent addition to the Ark USA list is Tuscarora corn, an endangered native species grown by the Five Nations Native Americans in upstate New York. The corn's inclusion on the Ark has led to the acquisition of a mill and roastery and a growing market for the cornmeal, which lends a measure of economic stability for those who grow and process it. And the toasted cornmeal has found fans among restaurateurs, who have incorporated it into their menus.

Given its protected status, the corn may take off with growing sales among consumers and inspire more planting, or it may remain a mostly local item, but at least it has a fighting chance. Bowman noted that with foods on the Ark, "We're trying to create a market nationally, but realize many [of the foods] are regional" and may best succeed by staying close to home.

This mission to save foods may seem a tad romantic, but the committee's goals are ultimately practical with a definite long-range view. The selection committee's mission statement puts it explicitly: "Future opportunity, not nostalgia for the past, will guide our selections." They also prioritize locally grown and created products as much as possible.

Bowman described Slow Food as "very grassroots" but with larger ambitions. "We're appealing to, and conserving, the traditions [connected to] local foods," she said. Among the local produce to make the Ark USA list are Blenheim apricots, a tree-ripened fruit that blemishes easily and won't travel well, but bursts with exceptional taste. The Sun Crest peach is also on board for similar reasons. Bowman conceded that Sun Crests aren't cosmetically perfect. They're "fragile, but inside they're the definition of what a peach should be," she said.

Hopefully, having a place on board the Ark will help these fruits find a bigger share in the marketplace. More people enjoying locally grown foods picked at the peak of ripeness would mean less unripe fruit being planed, trained, and trucked around the world to supermarkets where it sits, perfect-looking but tasteless, the culinary equivalent of Pamela Anderson.

The Ark doesn't stop at produce. Other local foods to make the cut include the red abalone, Northern California heirloom turkeys, and Vella Cheese Company's dry aged Monterey Jack Cheese. Fifty years ago, dry aged Jack was produced by over 60 cheese makers as an alternative to Parmagiano Reggiano, which couldn't be imported from Italy due to wartime complications. Vella is the last remaining producer of this tasty little slice of history, which now at least has a fair shot at surviving into the future. The hope is that if more people are inspired to buy it, more cheese makers will begin producing it again.

The Pleasures of the Table

The benefits of local foods are a cornerstone of Slow Food's way of thinking: fresher, healthier produce; lower prices for consumers; more income for farmers; more diversity on the farms; less packaging and pollution from transportation. A localized food economy is stronger than one that relies on the imports of transnational corporations, whose vision of diversity tends to involve 10 boxes of cereal with identical ingredients but different labels.

Dimock said one of his main goals as a Slow Food member is "getting people to think about regionalism" as a step toward more sustainable living. "Food is the cornerstone of sustainability and part of [our sense of] community." One of Slow Food Russian River's last events was a tasting of duck paired with a variety of Russian River wines, a great way to discover local treasures.

This doesn't mean all foods from overseas are forbidden or even should be--many convivia stage dinners of authentic ethnic cuisines featuring imported specialty items. Slow Food simply gives priority to the same types of food they always do, regardless of the nation they originate from: those produced by artisans and small-scale farmers for whom quality is key.

Yet another way Slow Food affects change is through community involvement. This starts with consumers and food producers, but extends further into the lives of those involved. The San Francisco convivium has worked with a program that brings chefs into Tenderloin area schools to teach the kids how to cook.

Slow Food Russian River is currently searching for a group with whom to form a similar sponsoring partnership. Dimock has nominated the Occidental Arts and Ecology Center-- "They're awesome," he enthused--because the nonprofit (formerly the Farallones Institute) shares his interest in permaculture, rammed-earth building techniques, and an intense commitment to sustainability at every level of civilization.

Slow Food Sonoma County has worked in close partnership with young men in Forestville's Sonoma County Probation Camp, taking them from the garden plot to the dinner table and beyond. The 16- to 18-year-olds grow food in a schoolyard garden, harvest and replant the produce, then learn to cook (and eat) it. This year they're hoping to grow enough produce to sell some at a farmers market. Working under the supervision of camp chef Evelyn Cheatham, one of the boys grew skillful enough to apply to the Culinary Institute of America. He was also given the honor of helping cook dinner for 150 members attending the first Slow Food USA national congress, held last summer in Bolinas.

If images of kids growing their own food and learning to cook it rings a bell with Bay Area residents, there's a reason. The idea is similar to Alice Waters' Edible Schoolyard program, which also teaches kids about food, from garden to kitchen to belly. While Waters embodied the Slow Food aesthetic before the movement even had a name, she's now the leader of one of Berkeley's three convivia, giving her another platform from which to spread the gospel of biodiversity, ecology, gastronomy, and tasty, tasty food. That focus on clean, pure, sustainable foods is at the heart of some contentious issues these days, and it's one of the areas where Slow Food practices radical common sense.

Home Cookin'

The government's continued refusal to label genetically engineered foods, even as they've come to occupy over 60 percent of the products on supermarket shelves, has taken control of what we eat out of the hands of consumers. With 93 percent of Americans polled by ABC News saying they want these foods labeled--a number that rivals President Bush's much-touted approval rating--the lack of any response has made many feel that their worst fears are justified. And what few kernels of hard evidence have been brought to light thus far have done little to assuage those fears.

The official position of government and science claiming these foods are benign was dealt a significant blow last fall by a New York Times report which found that genetically engineered corn DNA had contaminated some of Mexico's purest and most genetically diverse corn, despite the fact that genetically altered corn has not been approved for planting there. There's concern that the modified genes may begin to dominate the population and threaten the genetic diversity that made this corn so special. Largely heirloom species, some varieties are passed on from generation to generation and only grown by subsistence farmers in remote areas. Scientists still don't understand--and certainly didn't seem to anticipate--how genetic material could move so far, so fast. However, if it can get to some of the most well-hidden corn on earth, there's little doubt that our day to day "organic" foods may have been similarly exposed.

Knowing that organic crops grown near GMOs are at risk of contamination by gene transference--as are the people, animals, and insects who live near them and share the land--it's hard not to want to affect change. With the amount of these products appearing (still unlabeled) in floodlike proportions, an idea like the Ark takes on a new, urgent significance. Slow Food consistently champions those small producers who do the work of keeping food clean and pure themselves, and don't rely on Monsanto Corporation for pest control.

Slow Food members hope that preserving biodiversity and the pleasures of the table will help the communities involved to become more self-sufficient, and that the fun involved will keep them committed. With their protest-as-dinner-party approach to things, and as long as people stop and follow their taste buds, it's a good bet that the movement will succeed in its own sweet time.

[ North Bay | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Head Games: A wild-boar roast was one of Michael Dimock's slow food moments.

For more information on Slow Food and how to become a member, see www.slowfood.com.

From the June 6-12, 2002 issue of the North Bay Bohemian.