![[MetroActive Arts]](/gifs/art468.gif)

[ Arts Index | North Bay | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Wrap Act

Reflections on a religious icon and the art of dying

By

I ROSE EARLY on Easter Sunday, shortly after daybreak. With a thermos full of coffee and a few well-chosen medical supplies, I left the house and headed for the cemetery. I had a date with Jesus. Our rendezvous had been planned since last fall, ever since I bumped into Mary's favorite son while strolling through the graveyard's peaceful mausoleum. He was a statue, almost life-size, carved in wood, propped up at the end of the corridor. The arms were outstretched, hands upturned to display the famous gaping nail wounds, painted Day-Glo red for maximum shock value. Though the artist obviously meant for Jesus to appear transcendent, God-like, reaching out to beckon us all lovingly to his side, to me he looked like some poor guy saying, "Hey, man, can I borrow a Band-Aid?"

I'm serious. And I truly mean no disrespect.

My first impulse when I saw the thing was to jog home for some gauze and surgical tape.

I'm 40 years old. At various times I've been an Episcopalian, a Methodist, a Baptist, and a "nondenominational Born-Again." In short, I've seen my fill of bleeding Jesuses. The only thing they have ever inspired in me--beyond a certain revulsion--is sympathy. So gazing upon this one, all I wanted to do--and I really wanted to do this--was to bandage those hands.

But I resisted the urge. Still, I couldn't get the notion out of my mind. I kept thinking of those mangled wooden hands, imagining them all wrapped and bandaged, safe and sound. Yet the very idea of a bandaged Jesus, a healed Jesus, runs counter to our expectations. It's abnormal. It's spooky. "A triaged Jesus! What the hell is this? Hey, where're the damn nail holes?" It's obvious that, with or without the whole sacrifice-and-salvation view of the crucifixion, a lot of people just plain like to see Jesus bleeding.

The history of Christian religious art is, in many ways, one long odd tribute to our fascination with the bloodstained corpse of the poor carpenter from Galilee. The crucifixion, clearly, ranks among the most powerful and oft-repeated images in Western art. From Hieronymus Bosch and Michelangelo to El Greco and Rembrandt, from Paul Gauguin and Pablo Picasso to Andres Serrano and Salvador Dali, few major artists seem able to resist doing Jesus on that cross.

Whenever artists dare to tinker with the sanctified symbol of the gleefully murdered Christ, a hailstorm of controversy inevitably rains down on them. But these are often the most daring and, one could argue, spiritually transforming images of Jesus that we have. In Man of Sorrows: Christ with AIDS, painter W. Maxwell Lawton transposes Jesus' suffering into modern terms by taking him off the cross and showing him shirtless and silent, his nail wounds replaced by telltale body sores. Arthur Boyd's Crucifixion, Shoalhaven gives us a cross erected in the midst of a flowing river, and its naked, crucified Savior breaks tradition by daring to be a woman, thus insisting that Jesus truly represented all humans. These works are controversial, to say the least. Serrano's Piss Christ is perhaps the best, and least understood, example of what happens when an artist throws the cross into a different light. So incensed were Christians by the infamous photograph of a crucifix floating in urine that they never bothered to ponder the deeper meaning of the work--or recognize its visual beauty--calling vehemently for an end to the National Endowment of the Arts funds that helped pay for the exhibition.

Perhaps a crucifix floating in a vat of blood would be more to their tastes.

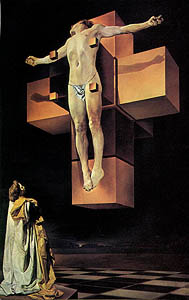

Even back in the days that I believed Jesus died as a sacrifice for the sins of the world, I was uncomfortable about our obsession with the gory exhibitionism of so many Christ images. I preferred the laughing Jesuses, the meditating Jesuses, the living Jesuses, to the battered, blood-drenched ones. Even resurrected, Jesus always seemed to be leading with his wounds. Whenever I found a crucified Jesus that did not repel me, it was usually one that minimized the wounds and maximized the humanity. My favorites include Gauguin's Yellow Christ--a jaundiced Jesus draped on the cross, breath-stopping despite its lack of oozing wounds--and Dali's Corpus Hypercubus, showing Jesus floating before the cross in a crucified pose, not a sign of nail prints--or even nails--to cast the ghastly shadow of sadism onto the otherwise heightened beauty of Jesus.

Yes, I understand that the idea of salvation, as symbolized by those ever- clotless, public execution-made lacerations, is itself a meaningful and powerful and beautiful thing to many. So what? If we love Jesus, why would we want to keep the guy crucified?

AS I THOUGHT of the statue in the mausoleum, I couldn't avoid thinking that the crucified Jesus, as art, is a symbol of more than salvation and sacrifice. It's a symbol of psychological damage on the human species.

A friend of mine who's done a lot of traveling once remarked that while passing through some of the world's most impoverished, disease-ridden, politically oppressed countries, she began to notice that the local religious artworks, in and around the churches and chapels, tend to be stunningly gory. The images of Jesus--whether they show him in mid-crucifixion, being laid to rest in the tomb, or right after the Resurrection--are positively dripping in blood. As she continued through the tiny villages of central Mexico, it became clearer and clearer: The worse off the people have it, the worse off their Jesus is.

The reason is fairly obvious. According to Christian tradition, Jesus came to offer comfort. Even the thought of Jesus' death--an event the early church spinmeisters turned into a metaphysical blood-for-sin exchange, bringing salvation to the world--offers comfort to those worried about what happens after death. If certain cultures are subconsciously moved to put their paint-and-plaster saviors through the artistic Cuisinart, it's clearly because doing so makes them feel better. So they erect crucifixes bearing corpses so pummeled that they barely look human. In the face of a Jesus so unimaginably brutalized, their own suffering diminishes in comparison.

But what's our excuse?

Are things so tough in America that we need to make our statues bleed just to feel more whole? Is the stock market so bad, are the crime rates so high and the high school test scores so low that we need to find comfort by running into a sculpture with its hands and feet punched full of holes? Is this a tradition we really need? I don't.

So this year, I initiated a new tradition. While others were sleeping, or scattering Easter eggs on their lawn, or gathering on mountaintops for sunrise services, I found Jesus, I touched those twin faux nail-prints painted on those hand-carved hands--and I wrapped the hands carefully in clean white bandages.

Standing back to look upon my handiwork, I experienced what can only be called a religious experience. A mix of emotions moved through me as I looked at Jesus, his arms outstretched, his scars invisible beneath the soft, soothing gauze. And that's how I left him.

While I have only the wispiest illusions that my little act of philosophical performance art could ever become a national movement on a par with tying yellow ribbons on trees during times of international strife, I like to imagine that my act may be repeated in years to come by those who, like myself, were moved by the unexpected sight of a bandaged Messiah, and are inspired, on future Easters, to make their own offer of comfort to a champion comforter. The way I see it, Jesus has been bleeding for 2,000 years.

It's time to let the man heal.

[ North Bay | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Clean cut: In his 1954 painting 'Corpus Hypercubus,' Salvador Dali created the perfect crucifixion for the technological age.

Clean cut: In his 1954 painting 'Corpus Hypercubus,' Salvador Dali created the perfect crucifixion for the technological age.

From the May 3-9, 2001 issue of the Northern California Bohemian.