![[MetroActive Dining]](/gifs/dining468.gif)

[ Dining Index | Sonoma County Independent | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Great Plates

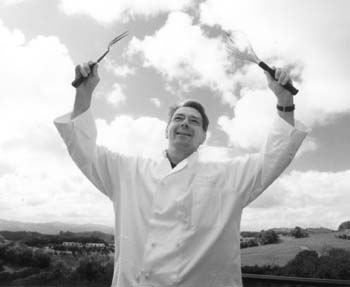

Reaching for inspiration: Richard Strattman of Chalk Hill Winery often wanders the oak-studded hills of Healdsburg when working up new menus.

How chefs create--Helpful hints on inventing new dishes

By Marina Wolf

WHEN CHEF Richard Strattman works up menus for the Chalk Hill Winery, he's usually out biking or wandering the oak-studded hills northeast of Healdsburg looking for wild mushrooms or spring nettles: anywhere, in other words, but the dining rooms where his creations are served up. Today, though, he's agreed to sit still and do it, to break down the process for a visitor who hopes to learn something, anything, to make her cooking at home more creative.

In the quiet sunlit room at the winery, the session starts out encouragingly enough. Strattman pulls out a blank menu template for a lunch that will be served to a small visiting trade group to show off the newly released 1997 wines. Strattman has also brought up printouts from his recipe database, sorted by season and wine affinities, and a great flapping foldout listing ingredients from past springs: green garlic, asparagus, lamb.

The manifesto, or "cheat sheet," is clearly used. "I need a lot of cheating," he says. "If I need a real light seafood dish for sauvignon blanc, I can think of maybe six off the top of my head. But with the databases and manifestoes I can come up with dozens."

Great. Make a photocopy, buy a recipe database. That's easy enough. But when Strattman begins jotting down dishes and techniques, and amending, things speed up. He explains why most of what he puts down isn't difficult: a light seafood salad based on whatever he finds on the market that day, tamales filled with rabbit, which was braised in quantity for another group of visitors two days beforehand. Deliberate leftovers, in other words, a tactic many families are familiar with. But where the home cook might have sweated over cookbooks for hours, Strattman has plucked out his elegant little lunch in less than 15 minutes; it probably would have taken him five if he weren't explaining as he writes.

The sheer volume of his repertory, whether in his head or on a cheat sheet, accounts in large part for Strattman's speed, and it's one key difference between the professional and home cook. But often what's called culinary creativity is in fact a highly trained attention to external factors--product availability and quality, the diners' tastes, the purpose and tone of the event--and a flexibility in incorporating them into the meal.

Cal Uchida, executive chef for the Sonoma Moment grape-growing and olive oil estate, is renowned for his innovative responses to the challenge. And even a more casual occasion, such as a recent dinner at his pastor's home, gets the same basic approach. "The people are more casual, I'm meeting his family; I don't know their likes and dislikes," relates Uchida, who eventually decided on a simple grill menu and a group-effort dessert.

But winery chefs such as Strattman must deal with an even larger set of constraints, says Mary Evely, the executive chef at the Simi Winery and author of The Vintner's Table. For wine chefs, everything revolves around wine. In a restaurant, Evely decides what wine she wants to drink and then finds a dish to go with it. "Wine is a fixed item," she explains firmly. "You can't ask the winemaker to run up and put together a nice little wine to go with the dish that's on the table. But you can change things in the food preparation."

Fortunately, making those changes in the food preparation and adapting dishes and menus is something that can be learned. "Most people have a much better [cooking] talent than they're aware of, and they just don't pay attention," Evely says. "You have to put some thought into it if you want to be able to go a little crazy in the kitchen. You have to at least think about, you know, categories of food. ... If you've never tasted basil and you've never tasted cilantro, you won't have a clue as to what will happen if you substitute cilantro for basil. So it does require paying attention when you're tasting things and remembering what they taste like."

Strattman advises home cooks to take the time and think about what they are doing. "Sautéing, roasting, braising--these techniques are in any book, so get a handle on the basics," he says, flipping through his books. "It's like music. Learning one recipe at a time is like learning one song at a time. But if you understand some chromatic scales, then you can read any music."

THE ASPIRING artiste also needs a muse, which, like beauty, can be found in anything. Evely frequents farmers' markets all over the county to see what the season and weather bring. Books and magazines are another way to get inspired. Rather than whipping up a recipe exactly according to spec--from, say, the March issue of Food and Wine--many chefs use the text and pictures to spark new creations or tangents from the original idea, or to dig up support for their concepts. Uchida heads straight for the books when he's planning a new menu for an event.

"I love to look at pictures, cookbooks, recipes," he says excitedly. "Things will just start popping up off the pages."

Michael Quigley of Cafe Lolo reads books and magazines, too. But like all chefs, Quigley is perpetually on the run, so more often than not the ideas and images and flavors go into his head and, well, stew for a while. "I have all of these ideas orbiting around in my head all of the time, and I just grab one down once in a while," says Quigley. "Like I have this one that's been orbiting around in my head for seven years, and I'm finally going to do something with it on our next menu."

Quigley might take his creation into the kitchen and test a little bit if he gets a chance. But mainly he works off the cuff. "To be honest, I've had dishes that I haven't even made until we start the new menu. And nine times out of 10, that works the best."

Bea Beasley of Beasley Catering and Event Management agrees: "Many things I've never made before in my life, but I can feel it. I can taste in my head, or I can see something, or maybe I've tasted it in a restaurant, and I can re-create it." She says it's a gift, which is a depressing thought for those cooks who yearn for a little of that spark in their own kitchen.

Is there any way to warm oneself on the fire of culinary creativity, without having to go to cooking school? Short answer: yes. Long answer: yes. And here's how:

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Michael Amsler

[ Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

From the April 22-28, 1999 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.