![[MetroActive Books]](/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | Sonoma County Independent | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Bukowski Lives!

America's gritty literary voice will never be silenced, thanks to Black Sparrow Press

By Patrick Sullivan

TUCKED AWAY in Santa Rosa's tiny warehouse district, not far from the St. Vincent de Paul dining room and the homeless camps by the railroad tracks, is a small tan building that might just be the perfect monument to the late author and professional hellraiser Charles Bukowski.

Cross the gravel parking lot, pass the neat row of cat dishes on the front porch, step through the glass door with the distinctive logo, and you've entered Black Sparrow Press, a tenaciously independent publishing company that continues to flourish in the increasingly treacherous world of book publishing, much as Bukowski himself survived against all odds and expectations.

Beat writers lived hard, and Bukowski lived harder than most. No teaching gig or writing workshops for him: Bukowski's rough-and-tumble exploits in the non-academic fields of drinking, fighting, and gambling were almost as much a part of his legend as his gritty writing. He went from a brutal childhood to a hardscrabble working-class existence to a profoundly uneasy relationship with fame and fortune. But despite all the rough stuff, for more than 50 years Bukowski wrote and wrote hard, publishing more than 45 books of poetry and prose during his lifetime, including such novels as Post Office and Hollywood, to sustained popular demand and growing critical acclaim. The ink finally stopped flowing upon his death in 1994.

The Black Sparrow offices, which are inhabited by more cats than people, seem like a place where Bukowski, who himself lived with nine felines, would feel at ease. That's no surprise. After all, the company was born out of a deep affinity between the eccentric writer and Black Sparrow owner John Martin. In 1966, Bukowski was discovered laboring unhappily and writing in obscurity in Los Angeles by Martin, who promptly founded Black Sparrow to publish the author's work.

Thirty-three years after this unique relationship began, Martin is hardly shy about rating his top writer's importance to the literary world. As he points out, most fiction and poetry does not stand the test of time. But how about Bukowski? Will his writing still be read in 2050?

"Damn right," Martin replies firmly. "He's the equivalent in today's world of Walt Whitman, who was accused in his own day of all the things that Bukowski was, of being a ruffian and uncouth. When you read Whitman now, there's nothing like that at all in his work."

It's easy to be overwhelmed merely by Bukowski's incredible output. This is the man who wrote his first novel in a month, who sat down nearly every night of his life to write for hours (after a long day at the racetrack, naturally), who could not be kept from his craft by advancing age or a terminal leukemia diagnosis. Even after he got the worst possible news from his doctor in 1993, Bukowski kept on working. A few months before his death at the age of 73, he managed to finish his final novel, Pulp, a surreal detective story starring a hard-boiled private eye who bore a striking resemblance to his dying creator.

"It was kind of his farewell to his readers and friends," Martin explains. "They're all in there under different names. And then he kills himself off at the end of the novel."

Bukowski is dead, but that doesn't mean you'll stop seeing previously unpublished work by him. Martin says that the poetry the author left behind is enough to fill five more fat volumes. (See sidebar, page 23, for one of these previously unpublished pieces.) Black Sparrow is also set to publish a third volume of the author's letters. All this begs a question that may also take us to the heart of Bukowski's unique talent: Why was he so prolific?

"'Cause he didn't mess around with his own head and ask himself a lot of stupid questions," Martin replies. "You know what a natural is in baseball? A guy who can just pitch, who pitches so well that his coaches don't mess around with his delivery, though it may not be orthodox. Bukowski knew how to write and he knew what he wanted to say. ... He didn't do anything that would make him stop and think about the mechanics of what he was doing, because he had that down from day one."

Or, as the author himself once put it, "Writing chooses you, you don't choose it."

THE STYLE that Bukowski employed was deceptively easy-looking. It seems almost lazy, right up to the moment it knocks you on your butt with a hard right hook that you never saw coming. Martin calls that prose "clear" and "straightforward" and "powerful." But that, he adds, is not really why he admires Bukowski's work.

"I don't give a rat's ass about style," he growls. "There are a lot of people who can write circles around each other, who are beautiful stylists. I prefer people like Bukowski or [Theodore] Dreiser. Bukowski became a very good writer in his prose. But his desire was to communicate, and if you communicate a genuine emotion or something really important, it will have much more effect on the reader than a lot of pretty prose."

Biographies of Bukowski seem almost redundant next to his work, which was focused sharply on his own life. That was the subject matter that Martin, along with millions of other readers, found so compelling. Bukowski wrote with graphic directness about experiences that many people have every day--working hard, drinking hard, being disgusted by a world that is apparently determined to disgust and annoy you. Post Office, the novel about the brutal world of postal work that has sold more than a million copies in a dozen languages, may be one of the most compelling works American literature has to offer about working-class life. As another example, Martin offers the classic Bukowski poem "Shoelace."

"It's about how you're having a bad hair day, and everything is going wrong, and the one thing that just snaps and plunges you into an abyss of despair is if, when you're tying your shoes, you break your shoelace," Martin says. "People can relate to that."

It was on this firm foundation that Bukowski built his literary career and John Martin built his publishing company. As Bukowski's star rose, he attracted an often uncomfortable amount of attention. Two movies--including Barfly, starring Mickey Rourke and written by Bukowski himself--were made about his life. Madonna asked him to be in her Sex book. Fans and groupies sought out his house from all over the globe, sometimes masquerading as journalists to get a few minutes with their hero. Did all of this frantic hype change the plainspoken working man?

"Not at all," Martin says. "Me neither. We just got better cars."

Of course, even that process wasn't without complications, as Martin relates. Even after he became successful, the author continued to dress plainly in flannel shirts with pocket protectors. So when Bukowski walked into a Lexus showroom looking for a new ride, the salesman barely looked up from his desk. He only reluctantly came over at Bukowski's explicit request. But the salesman's day perked up quite a bit when the author explained that he'd be paying in cash.

The only other change Martin notes was that Bukowski's wild lifestyle calmed down as he got older.

"He drank because he was unhappy," Martin says. "When he stopped being unhappy, he drank less. And then he finally drank nothing but very fine wine, which is not as bad for you as the stuff he was drinking prior to that."

Bukowski may have been Black Sparrow's most prolific writer, but he's not the only talent on the team. Martin has published everyone from Joyce Carol Oates to Andrei Codrescu to Wanda Coleman. The 68-year-old publisher, who has not taken a day of vacation since 1974, still personally selects all of Black Sparrow's books. And his criteria haven't changed since his first big discovery.

"I'm looking for the same reaction I got when I read Bukowski or Paul Bowles, whom I publish now--just that kind of 'here it is, in your face' quality," Martin explains.

In the vast ocean of paper pulp that modern publishing has become, it's Martin's willingness to take a chance that may do the most to distinguish Black Sparrow.

"You just publish what you like and hope that there are a few thousand people out there who will agree with you," Martin concludes.

[ Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

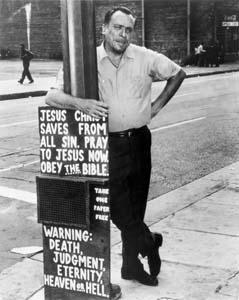

Judgment day: The work of Charles Bukowski appears to be passing the test of time. Here the author is captured on the mean streets of L.A. about 1970.

Judgment day: The work of Charles Bukowski appears to be passing the test of time. Here the author is captured on the mean streets of L.A. about 1970.

Bukowski Poetry Contest: WINNERS WILL BE announced, poetry will be read, and prizes will be awarded in the second annual Bukowski Poetry Contest on Friday, April 30. The event--which is co-sponsored by Copperfield's Books, Black Sparrow Press, and the Sonoma County Independent--begins at 7 p.m. at Copperfield's Books, 650 Fourth St., Santa Rosa. For details, call 545-5326.

From the April 22-28, 1999 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.