![[MetroActive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

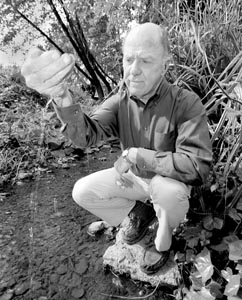

Photograph by Michael Amsler

Man with a (Green) Plan

Conservationist Huey Johnson knows how to save the planet

By Stephanie Hiller

FORGET ALL THAT doom and gloom about the destruction of the environment. Government and business may not be doing things sustainably yet, says conservationist Huey Johnson, 67, former state environmental czar under the Brown administration, "but they will." Why? Because they'll have to, he says.

As director of the Resource Renewal Institute in San Francisco, Johnson travels around the world to discuss what he calls "green plans," engaging governments and businesses in deep conversations with environmental scientists to generate blueprints for sustainable development. "I see successful models elsewhere in the world," he explains. "Others are doing it; so will we."

His travels bring him to Healdsburg this week, where he will speak about the increasing threat to the Russian and Eel rivers.

From the Netherlands to New Zealand, governments have been working collaboratively with businesspeople and environmental scientists to virtually redesign their society to eliminate pollution and utilize renewable resources. "When you see what they're doing in Holland, it'll blow your socks off," Johnson says. "And what's sustainable is economically viable. Holland has the best economy in Europe."

Johnson's optimism about a sustainable future doesn't stop him from pointing out what's wrong with current governmental practices. For example, calling the Sonoma County Water Agency's operation a "shell game" designed to confuse and delude the public, Johnson finds it "almost humorous they way they run the water distribution [system]. The fact that they allow gravel mining in the main artery which maintains the quality of life of the region, that makes no sense at all."

TO STOP THE DECLINE of the Russian River, he says, it must first of all be designated a wild and scenic river. "We could have a clear plan for managing the river as a heritage resource by an independently established resource group, with a trust fund of $20 million for research, education, politics," he suggests.

Wild rivers must have a sufficient flow to maintain fisheries, with limitations placed on how much water can be used for residential and agricultural uses. That requires the careful monitoring of consumption.

A Marin resident, Johnson is totally opposed to sending Russian River water to Marin communities. The Marin Municipal Water District now gets about 25 percent of its water from the Sonoma County Water Agency. That's 8,000 acre-feet of water, and the agency has a contract to take up to 14,300 acre-feet. Controlling the future sale of water will definitely limit growth in the North Bay region, a policy that Johnson believes should be a goal throughout the United States.

As the need for water increases, he adds, "we're going to have to fight hard to keep these wild rivers and to create and maintain a sense of the precious heritage that they represent."

Sound water policy would take a regional view of the demands on the Russian River watershed and use that perspective as the basis for managing its uses. If the Eel River diversion to the Russian River is cut off to save the Eel's beleaguered fisheries, which Johnson believes is inevitable, "you'll learn how to manage your water better.

"There used to be a quarter million steelhead in that river," Johnson explains. "Bring back the steelhead and you'd have the fishermen coming back, spending money in your restaurants and hotels. Tourism is a much better business than manufacturing.

"It's the only thing that can last."

He also believes that the gravel-mining industry has to be stopped from damaging delicate riverbeds. "People want gravel because they want to build things," Johnson says. "In Marysville [in the Sierra foothills], there's enough gravel there to last a hundred years, and it's all above the ground," the residue of gold-mining operations.

But campaign contributions and influence peddling promote county officials' continued support of the gravel industry.

A trip to the Netherlands might cure all that--Johnson actually took the Marin County Board of Supervisors there to prove his point.

All 440,000 Dutch industries support the National Environmental Policy Plan adopted in 1989. That plan is a comprehensive approach to industrial manufacturing, regulation of natural resources, and recycling and reuse of consumer products. The phenomenal success of Holland's environmental management is what inspired Johnson to form the Resource Renewal Institute and begin speaking to public officials and activists in other countries and states about developing green plans.

"To succeed," he says, "everyone must be part of the discussion, especially business. In Oregon, Minnesota, New Jersey, wherever we've got a governor who's interested, we show them a better way of doing things. We spend some time selling the idea. One of the remarkable accomplishments of America is that we know how to manage our affairs. But for some reason we don't apply those principles to the environment."

Does it make sense to import mussels from New Zealand when there's enough protein growing on the rocks of the Marin/Sonoma coast to supply all the protein we need? he asks. "This is 'stupid management,' " Johnson says bluntly.

He doesn't blame anybody for such short-sighted practices. Instead, he says, you have to recognize the pressures that officials are under.

JOHNSON'S perspective stems from a unique combination of experiences in industry and government as well as conservation. Raised in Madison, Wisc., "when 10-year-old boys could take their guns and go rabbit hunting, and people trusted them to do that," he got a job in the chemical industry after graduating from college.

He was doing very well for himself making plastics for packaging, until one day he noticed that all the plastic packages "stacked up as big as a house" behind one of his customers' warehouses. He left his job and traveled around the world for a couple of years to do a little soul searching.

It was, after all, the '60s.

"I very clearly saw that many of the conflicts of history had been over resource allocations," he says.

After taking on a number of different jobs--including commercial salmon fishing--Johnson attended graduate school at the University of Michigan in the environmental management program. After that, he built up the Nature Conservancy, one of the most influential environmental organizations in the world, but when he saw it was serving only the elite, he created the Trust for Public Land to save open space in America's urban centers.

One day, then Gov. Jerry Brown asked Johnson what he thought of his administration. In response, Johnson gave him low grades on the environment. Brown agreed to create a new cabinet-level post to deal with environmental issues and persuaded Johnson to become secretary of resources to help shape things up.

Johnson never looked back, continuing to this day to work tirelessly as a respected environmental activist.

"Humanity knows enough to solve the environmental problems," he says. "But we've been making the mistake of thinking we can do it in one policy after another when in reality we're managing a system."

Now Johnson applies systems theory to the task of managing the environment. "I was down in Silicon Valley last week, where industry is very, very clean," he explains, "but then you go outside and you can hardly breathe the air. Everyone is so focused on making widgets that they forgot about the air their children breathe!"

But is industry ready to do its part to live within the limits the environment requires? "We liberals make the mistake of painting everything with one brush," he concludes.

"We have to judge industry on a broader scale. Most of the businesses in Sonoma County would have no problem being environmentally clean."

[ Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

A resourceful fellow: Former state environmental czar Huey Johnson says that European nations have created a model for saving threatened natural resources in the States. He speaks this week at a local environmental conference.

A resourceful fellow: Former state environmental czar Huey Johnson says that European nations have created a model for saving threatened natural resources in the States. He speaks this week at a local environmental conference.

Huey Johnson will be the keynote speaker at Free the Rivers, an Earth Day educational workshop sponsored by Friends of the Russian River, to be held Saturday, April 22, at 8:30 a.m., at the Raven Theater in Healdsburg, For details, call 524-9377.

From the April 20-26, 2000 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.