Cafe Society

Michael Amsler

Richard Allen likes his food alive

By Marina Wolf

EARLY SPRING in Sonoma County is more lion than lamb; even on a good day the clouds throw undecided shadows across such places as the graveled parking lot of Santa Rosa's Willowside Cafe. But inside the kitchen, Willowside's chef-partner Richard Allen is ready for the sun, wearing bright shorts and full of enthusiasm about the food of Southeast Asia and the Caribbean, which he visited this winter.

"I like that whole zone," he says, stirring up a vibrantly yellow coconut milk-turmeric sauce that will surround tonight's vegetarian dish. "I like all the things that grow in that area: ginger, coconuts, peppers. They make food come alive."

The tropical influence is relatively new territory for Allen, but food that's alive is what pulled him into the restaurant business in the first place, and has evidently helped to make him a winner. Soon after Allen joined Willowside in 1994, Michael Bauer, food editor at the San Francisco Chronicle, wrote: "I'd be hard-pressed to find a restaurant that is as consistent and as able to coax the maximum flavor out of each ingredient on the plate." The Zagat guide noted the Willowside Cafe in 1997 and 1998 as outstanding in both the Mediterranean and the Californian categories, and a review is in the works for the May issue of San Francisco Focus.

That's a lot of hot press for a guy who was a bored postal clerk merely 17 years ago. Wisely avoiding any life changes that involved automatic weaponry, the then 31-year-old Allen signed on for a waiter/cook position at the Union Hotel in Benicia. He describes his food epiphany in almost religious terms. "I was Catholic as a kid, and we ate fish every Friday," says Allen. "We had fish cakes, fish sticks, fish loaf. But I never really saw fish until I saw them at the Union Hotel. The salmon was exactly what the books say: clear eyes, bright red gills, and the meat bounced back when you touched it. And then the chef, Judy [Rogers, now chef-owner of Zuni Cafe in San Francisco] made the plate, and it was like, 'Oh my God, this is real food.' I got out of the post office at that point."

Vivid sensory revelations are that much sharper against a backdrop of normalcy, and Allen's life to that point had been normal in the way that only those who came of age in the '50s could ever understand. He grew up in an Army family that moved all over the country and even to Germany. But with six kids in the family, the pennies got stretched a bit to cover three squares a day.

"It was cereal, it was very straightforward Americana," says Allen. "It wasn't experience, it was just food."

Other than a pubescent stint working as a carhop, serving burgers to attractive Southern Mississippi coeds, Allen didn't think much about food or cooking through his youth. Over 15 years would pass before he met that firm, fresh salmon in Benicia. But then the food-lovin' side emerged from his soul--with a vengeance.

He moved from the Union Hotel to a year and a half at Chez Panisse, Berkeley's fresh-food mecca, before he worked at Napa Valley's Domaine Chandon ("I learned how to hold a knife there") and then went on to his first chef position, at a Yosemite fishing lodge. Three trout seasons passed, and another two years at Domaine Chandon. Then Allen got hired as chef for a year at Jordan Winery in Healdsburg, where he encountered what he calls the double-edged sword of cooking for winery tours. "I had an unlimited budget," he says incredulously, spreading his hands apart for emphasis. "It was a 1, followed by many zeroes. I could do literally whatever I wanted; I could buy ingredients just to play around with."

But the constraints of pairing his creations with a limited selection of wines, and the boredom of many a tourless day, drove Allen away from that. After a brief hiatus, he got into the "salads and firsts" position at Willowside, and when the inevitable turnover left the chef position empty in March of 1994, Allen jumped from the fridge to face the frying pan, where, it seems, he likes to be.

"Sometimes I feel like it's a baseball game," says Allen when asked about the best and the worst of his work. "It's the bottom of the ninth, we're down by three, the bases are loaded, there are two outs, and the only way we can win is if I hit a grand slam. The purveyors are the pitchers, and they're all throwing me curves. Meanwhile, the dining room is full and there's a tremendous buzz; these are the fans." He pauses and grins. "I'll be standing back there with the sauté pan, but people will stop and wait to get my attention--then they give me two thumbs up. Boom! The fans go home happy, and the home team wins."

The home team, in fact, is riding a real winning streak. Since his arrival, Willowside has been listed three times in the Chronicle's annual top 100 restaurants of the Bay Area, among the other notices that are nowhere to be seen in the restaurant. "I don't believe in that," says Allen shortly. Or perhaps he doesn't need print praise hanging on the walls. The kitchen is partly open to the dining area, so Allen gets enough compliments from the customers as they pass. "But even if I could get away from the line to circulate among the tables ..." Allen stops short. "I could go on and on about this," he warns with a laugh, and doesn't need much encouragement to continue.

"A lot of chefs get too wrapped in that, and meanwhile something else goes on in the kitchen," says Allen. "You go away and rely on your next person, and if that person has any initiative at all, eventually they start injecting their taste and personality into your dish. You come back and you won't know it. I had one person work for me and I was afraid to go to the bathroom because I didn't know the menu when I came back."

But, as he says, that's part of getting ahead. "Show me someone who hasn't tried it, and I'll show you someone who'll be a line cook forever."

Does that mean he did it, too? "Of course I did. I'm not ashamed to admit it," he says. But he does try to encourage more openness in his own kitchen. "I talk with my people all the time about the menu, how can we change it, how can we make it better.

"That way I eliminate those kind of surprises," he grins.

Such low-key irony comes in handy for this bustling little eatery, that and some very firm ideas about the proper functioning of a restaurant and the people working in it. Take culinary academy graduates ... please.

"I've hired so many [of them], and I just want to shoot them," Allen says with a half-joking arch of his stern dark eyebrows. "They just paid beaucoup bucks to go to cooking school, but they've never washed lettuce in a restaurant. And you say, wash this lettuce, and they say, 'Wait, I'm a graduate.' Well, if you just graduated from medical school, you don't become chief of surgery. You do the bedpans first."

Or perhaps a more tasteful analogy for Allen's purposes would be, you can't get to summer without slogging through a sometimes-gray spring.

Our series on how Sonoma County chefs stand the heat of the kitchen.

Allen offers this starter as a salute to the season. This is a very vernal arrangement, with new asparagus shoots and tiny eggs against a backdrop of deep red sauce. And with asparagus now in season, you'll be able to rationalize the extravagance of two dozen end-of-season blood oranges and several quail eggs (look for the eggs in Asian markets) for four servings.

24 medium blood oranges, juiced and strained

8 quail eggs (or substitute 2 chicken eggs)

1 bottle sparkling wine

1/3 to 2/3 cup extra-virgin olive oil

Salt and pepper to taste

1 1/2 lbs. asparagus, trimmed and blanched

2 oz. pine nuts, toasted

2 oz. goat feta, crumbled

Over medium heat, reduce half the orange juice to a thick syrup, about 15 to 20 minutes (reserve the rest of the juice for accompanying drinks). Set the reduction aside to cool in a bowl.

Meanwhile, place the quail eggs in boiling water and cook for three minutes. Put the eggs in an ice bath. When cool, peel and halve (or if using chicken eggs, grate). Put a couple specks of black

Open the sparkling wine and slowly drizzle about 2 tablespoons into the juice reduction while whisking to give a loose consistency. Slowly whisk in enough oil to make a pourable sauce. Season with salt and pepper.

Ladle a pool of the vinaigrette on each of four plates. Arrange the asparagus in the pool. Place the quail-egg halves (or grated eggs) around. Sprinkle the pine nuts and the cheese over the asparagus.

Divide the reserved orange juice into four champagne flutes, no more than halfway up the glass. Fill the top half with sparkling wine.

[ Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

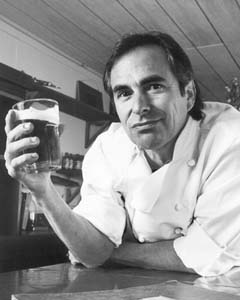

Haute stuff: A former postal clerk, Willowside Cafe chef Richard Allen has helped place that popular Santa Rosa bistro on the San Francsco Chronicle's prestigious Top 100 list of best Bay Area restaurants for three of the past four years.

Haute stuff: A former postal clerk, Willowside Cafe chef Richard Allen has helped place that popular Santa Rosa bistro on the San Francsco Chronicle's prestigious Top 100 list of best Bay Area restaurants for three of the past four years.

Asparagus with Blood-Orange Vinaigrette

pepper on the yolks.

From the April 16-22, 1998 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.

![[MetroActive Dining]](/gifs/dining468.gif)