![[Metroactive Books]](/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | North Bay | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

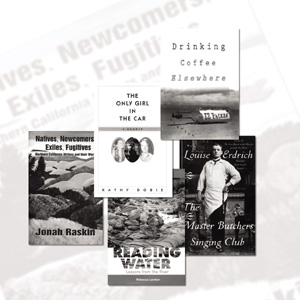

'Drinking Coffee Elsewhere' by ZZ Packer

A bevy of recently released books to escape into

It's hard to find time for pleasure reading these days. How can literature keep up with the stories available on TV or the web, stories more horrific and immediate than any writer could conjure up.

It's a cliché to say that literature is an escape. But what are clichés, if not true? And while the bombs are falling, the writers are still writing, and the publishing industry is still churning out the books. Thankfully. As Jonah Raskin makes clear in his new release, reviewed below, writers are a hardy breed, their work braced to withstand all manner of world affairs. So when the reality TV gets a little too, well, real, rest your eyes upon one or more of the pages described below. --Davina Baum

Packer Punch

Now that the memoir form and chick-lit à la Bridget Jones are traipsing down the road of no-longer-trendy, the short story is having a renaissance. And to that end, award-winning writer ZZ Packer could be the poster child for how to deliver a dazzling emotional punch in a fraction of the pages needed for a novel.

If Raymond Carver and Toni Morrison could have spawned a protégé, she would look a lot like ZZ Packer, a writer about whom you want to say, "I knew her when . . ." With her elegant, even startling new collection of short stories, Drinking Coffee Elsewhere (Riverhead Books; $24.95), ZZ Packer has exploded onto the literary scene with gusto and raw talent. Readers of this hearty book will not be surprised to discover that this Yale and Iowa Writers' Workshop graduate commenced her academic life as an engineering major; each story is a carefully wrought schematic of the inner life of its characters.

At times her characters are so visceral in their portrayals that you aren't sure whether to laugh or clap and sing along with them, like Clareese and the other Pentacostals who dominate the pages of "Every Tongue Shall Confess." Other times you are torn between despising or pitying them, as with Lynnaea in "Our Lady of Peace," a high school teacher by default whose angry students enact a struggle for power in the face of hopeless odds.

Set in stark, mostly urban situations--an inner city high school, a religious summer camp, in the midst of the Million Man March in D.C.--these stories are peopled with characters who themselves have no choice but to become the landscape. Their inner worlds are so layered and complex that a 30-page story flashes by all too quickly.

Packer places her characters on polar ends of a continuum; they are either outspoken or reticent, and brimming with longing and devotion to ideals. Some are hung up on their beliefs to the point of absurdity, such as the father in "The Ant of the Self," who, just out of jail, still expects his teenage son to pick up his slack.

In "Brownies," Packer throws the question of discrimination under an entirely fresh light, as a Brownie troop of black girls confronts a troop of white girls--with an unforeseen twist. In both stories, the characters act audaciously, pushing past comfort zones so that you are cringing with dread at the outcome and eagerly reading on because you just have to know how it turns out.

One of the most touching and painful stories in the entire collection is the book's namesake, "Drinking Coffee Elsewhere." In it, a black college freshman tainted by her messy home life, and a chubby depressed white girl begin an unlikely friendship that presses up against the edges of taboo romance. As with all of Packer's stories, it ends on a precipice, leaving the reader to take it the final step and fathom the plausible ending.

In this way, all of her stories have continuity. It is impossible not to keep thinking about her characters; they are so palpable, it seems they must have been lifted right out of the world around her. This, of course, is a sign of the careful and mischievous observer that Packer clearly is.

What makes Packer's stories so extraordinary is the weight of simple truths hidden inside surprising and undeniable turns of phrase: "Indiana farmlands speed past in black and white. Beautiful. Until you remember that the world is supposed to be in color." She uses substantial yet subtle metaphors to tailor a landscape that fits each character's life, avoiding the facile and common clichés that seem to slip into so much fiction. From Tia the 14-year-old runaway to Spurge, the cowed son of a criminal, Packer's characters leave you breathless and hungry for just one more story. --Jordan E. Rosenfeld

Something in the Water

As the title of Jonah Raskin's new book, Natives, Newcomers, Exiles, Fugitives: Northern California Writers and Their Work (Running Wolf Press; $15), implies, it's a volume for outsiders, wanderers, and hometown lifers alike. Numerous times throughout the book, Raskin, who moved here from New York, compares literary life on the two coasts, and I was stunned to read in the introduction, "When I first arrived from New York in 1975, our writers seemed few and far between. Folks ventured forth to see the prize pigs, sheep, and cows that the 4-H kids nurtured. . . . The fairs and fundraisers still go on, but now there's a book culture to go with the agriculture."

He's right. Things have changed. When I first moved here three years ago, I was immediately struck by how you couldn't swing a dead cat without hitting a person of the pen. Which is just Raskin's point. Northern California has, in the past quarter-century, not fostered a literary scene as much as a loosely-affiliated community of writers, bound by a love of this place.

Natives, Newcomers pulls together Raskin's Sunday book section columns from the Press Democrat over the past few years (his other work has also appeared in these pages), and the anthology covers a wide swath of writers: international bestsellers, local celebrities, cult favorites. Through profiles and interviews, Raskin takes a magnifying lens to 32 authors and their respective dots on the Northern California map, with a decided Sonoma County focus.

Unlike New York, Northern California has no one tiny slip of an island to pinpoint as the center of everything; our writers are spread out over valleys and mountains, from San Francisco to Mendocino. Sure, there are recluses, bohemians, lefties, hipsters, and showmen, but Raskin finds no distinct archetype, except that mélange of cultural experiences and values that California cradles.

Collectively, the columns form a vibrant tapestry. Every writer spins a thread, and a profound sense of place, rather than shared experience, binds them all together. Some of them no longer make their homes here, but there's a stamp of golden, rolling hills and towering redwoods burnished on their brains that they can't shake.

Natives, Newcomers also brings us closer to the region's literary big guns--Alice Walker, Amy Tan, Isabel Allende--and introduces (or perhaps reintroduces) us to writers whose works deserve a wider audience, like Gerald Haslam and Greg Sarris. Raskin's inclusion of nonfiction writers such as Alicia Bay Laurel (author of the back-to-the-land guide Living on Earth), celebrity chef Michael Chiarello (Napa Stories), and teen-guide writer Mavis Jukes (The Guy Book) keeps his book from having a cliquish "novelist's club" tone.

Mystery fans will be delighted to find profiles of Sarah Andrews, Bill Moody, Bill Pronzini, and Marcia Muller, while poetry lovers will appreciate insights into Jim Dodge, Diane di Prima, Don Emblem, and others.

The one problem with the book is that, outside of the excellent introduction, it maintains a fresh-from-the-newspaper feel. The columns could have benefited from additional revisions, either as updates or expansions. The writing is a mite too breezy to ideally settle into a meaty book. But there's a busybody delight in reading about all of the renowned authors whom we may be potentially rubbing elbows with at the supermarket. And Raskin's supplemental list of selected books by Northern California writers is helpful and well-chosen.

For the curious reader, Natives, Newcomers, Fugitives, Exiles offers glimpses of writers whose lives may or may not be so different from ours. It's constantly enlightening, and there is no way to escape the book's covers without feeling the hunger to search out works by the writers therein. --Sara Bir

Singing for Sausage

I recall some months ago opening the latest New Yorker and seeing to my delight that there was a story by Louise Erdrich, a perennial favorite. "The Butcher's Wife" was one of those stories with unpredictable characters, high emotion, odd details--the kind you loathe to finish, though once you have, you want to telephone everyone you know who loves fiction and insist they experience this fine thing too.

Happily, there was more to be had, as this was only an excerpt from her latest novel, The Master Butchers Singing Club (HarperCollins; $25.95), an ambitious book that begins on German soil at the wrecked finish of World War I and follows an intriguing population of German immigrants, traveling performers, scavengers, quirky Midwesterners, singing butchers, evil aunts, children, murderers, alcoholics, and veterans across many decades, even into and beyond the next "Great War." For almost four hundred pages we are plunged into the world of Argus, N.D., where love and death seem to strike with random gusto, and where "butchers sing like angels."

Erdrich's first book was the extremely well received Love Medicine, and besides writing six more novels since then, she has also penned poetry, children's books, and nonfiction. With her Ojibwe blood, many of her books have a Native American theme running through them, but The Master Butchers Singing Club is an exception. The book begins with Fidelis, a German sniper who manages to emerge from World War I intact, staggering into the hush of his childhood bedroom and sleeping for 38 hours, moved and shaken by a long-forgotten tranquillity and cleanliness.

Throughout the novel, Erdrich seems to define her characters by what they can endure. For Fidelis it is the slight guilt of the survivor; for his wife Eva, it is her illness; for their friend Delphine, it is never knowing her mother, and her slavish devotion to an alcoholic father; and for Delphine's partner, Cyprian, it is all that he too has seen in the war, as well as the secret of his sexuality.

Fidelis arrives in Argus with nothing but his prized knives and the incomparable sausages his father taught him to make back in Germany. But this is enough to create a reputation, and he eventually opens his own butcher shop with Eva. Meanwhile, Delphine and Cyprian are perfecting a balancing act with a traveling show where Cyprian performs handstands on a chair balanced on Delphine's stomach, for as she tells him, "My stomach's tough. Why not? I am not ashamed I grew up on a goddamn farm. I'm strong all over."

The two take their act on the road, pretending to be married so as not to provoke Midwestern disdain, but they eventually wind up back in Delphine's hometown of Argus, where duty reels her back to her drunk father and the reeking pigsty the house she grew up in has become.

Eventually, Delphine ends up face to face with Eva, the woman who comes to affect every aspect of her life: "The first meeting of their minds was over lard. Delphine was a faceless customer standing in the entryway of Waldvogel's Meats, breathing the odor of fir sawdust, coriander, pepper, apple-wood-smoked pork, a rich odor, clean and bloody and delicious. . . . She stood behind a display counter filled with every mood of red."The friendship that forms between these two women is a palpable force, even in the face of the numerous trials that will confront them.

Aptly, in a book involving butchers, there is blood: blood devotion, blood rivalry, and spilt blood, the latter not just in the obvious sense of the slaughter of the two wars that bracket the novel. Argus has its small-town share of skeletons, metaphoric and literal. Step-and-a-Half, a sort of visionary character, a rag collector always on the periphery of the book, is privy to the secrets of the townspeople through the items they discard.

Step-and-a-half is also a keen observer as she walks relentlessly, "the only way to outdistance all that she remembered and did not remember, and the space into which she walked was comfortingly empty of human cruelty." Yet ultimately, Erdrich reminds us, that earthly cruelty is always balanced with singing butchers. --Jill Koenigsdorf

A River Runs Through It

There are countless things in nature that capture our fascination. Flora and fauna instruct us on instinct and evolution; geology and geophysics council us on the vagaries of history and the truths of commuting energies.

But more often than not, the fascination with nature is less intellectual and more emotional, visceral. Rebecca Lawton, author of Reading Water: Lessons from the River (Capital Books; $18.95), echoes that instinctual attraction to a world free of concrete and rubber, an unconstructed world. In lyrical (sometimes purple) prose, she documents waterlogged, bumpy, yet joyous rides down the rivers of the western United States, weaving her rafting experience into a cohesive, nuanced portrait of a life spent loving the river. Part memoir, part geological and environmental primer, part meditation, and part adventure story, Reading Water truly earns its subtitle, "lessons from the river."

From her first view of the river as a 17-year-old on a summer rafting trip--the Stanislaus, in fact, was her first love--Vineburg resident Lawton felt the pull. "I'd come to the river for a weekend," she says in the introduction, "but I ended up staying for years." Lawton became a professional river runner, leading rafting trips all over the western United States. Now retired from professional guiding, Lawton says, "I'm still steering the craft. Constantly adjusting course."

The river as life. The rushing waters of the country's rivers are ripe for the metaphor-plucking; Lawton gorges herself on them. The lessons from the river that Lawton relates ripple out poetically in even, smooth circles.

Each chapter in Reading Water is an education in river lore and geology, as well as a window into the life of a river guide, that curious creature whose summers are spent rafting and whose winters are spent waiting for summer. Using various fluvial properties--damns and reservoirs, floods, cobbles, and deltas--as metaphors, Lawton travels through the death of her mother, her marriage, the birth of her daughter, divorce, the suicide of a friend, and near-death experiences on the river. There are less dramatic events too: A kayaking trip in Baja with new friends, learning to meditate, and lessons from other guides populate Lawton's tales.

One chapter introduces the idea of deliquescence, the "baroque divergence" of tree limbs or river tributaries. Lawton goes on to explain--via a narrative of her move to Pennsylvania, away from her beloved western rivers, and repeated trips back to California to watch her mother die of cancer--that deliquescence can mean becoming liquid through contact with the air; changing state. "Divorced spouses or deceased parents deliquesce, as certainly as ice melts in water, as they simultaneously never leave us."

The prose-ready riches of Lawton's chosen place of work do not escape her. She calls the river "a mother lode of metaphor" when turning the discussion to eddies, those swirling countercurrents in which a boat can get hopelessly stuck. An eddy "stands out as a precious diamond" in terms of metaphorical possibilities: "We can mine its real-life analogues endlessly, using language rooted in being stuck: backwater towns, dead-end love affairs, blind alleys."

Lawton uses her discussion of eddies to relay a defining moment--a graduation of sorts, from assistant Grand Canyon guide and apprentice to her brother, to full-fledged guide. "I'm fortunate to have waited and trained as I did," she explains, "because in all my rushing from river to river for experience, those days spent in limbo allowed me to reclaim my abandoned soul."

The chapters are strong by themselves, and many were published previously as standalone essays in other collections (including Susan Bono's literary journal, Tiny Lights). Taken as a whole, the essays create a composite portrait of the tenacity, passion, and dedication needed for a woman river guide (indeed, the gender gap plays a large role in many of the chapters)--as well as the tenacity, passion, and dedication of Lawton herself, on and off the river.

Yet taken as a whole the chapters also bombard the reader with metaphor after metaphor, and the repeated formula is somewhat tiring. While each chapter is a gem of experience and an education in river terminology, it becomes a guessing game to see how she will extend this geological term to that life lesson.

Luckily, the richness of Lawton's prose and the obvious depth of her expertise keeps the book afloat and navigates its lessons with a steady oar. --D.B.

Lolita Tales

Hormones often grow and explode faster than adolescent bodies and minds develop, and the poignant and painful fallout can go on to shape lives. Kathy Dobie, at 14, suddenly noticed boys and men--and, to her marvel, they noticed her. Her lust awoke before her bookish innocence was prepared for it, and one day, determined to lose her virginity, Kathy donned a candy-striped halter top and hip huggers and sat on her lawn, waiting for adventure.

She got it. The unfolding of events that followed, Dobie funnels into her memoir, The Only Girl in the Car (Dial Press; $23.95). She relates a familiar tale--too much, too soon--in an amazingly transportive voice.

Dobie, a journalist who's written for Vogue, Harper's, and Salon, among others, was raised Catholic in Hamden, N.J. Her father was in charge of food service at Yale; her mother was a housewife whose life was consumed with raising six children. Though the Dobie family was loving and close, young Kathy longed for attention and strove to be mommy's helper.

After years of being a pleaser and a good girl who was easily carried away by the potency of her own imagination, Kathy's senses in the space of one summer became hyperalert to the downy blush of man-boy faces and the laughter of roughhousing teenage guys. "I was fourteen and the world was whispering, whispering. I though it was talking to me in particular," she writes. Bold but guileless, she soon realized that the attention of males was easy to snag.

After her curiosity and longing led Dobie through an eye-opening series of sexual escapades (including an intentional encounter with a pedophile who clearly fancied her Catholic schoolgirl's uniform over her burgeoning womanhood), she discovered how thrilling and ephemeral physical intimacy was.

She also got a fierce reputation as a slut, especially at the teen center where she had taken to hanging out with a ragtag pack of dropouts and party-goers. When Dobie began dating the leather-jacketed Jimmy, she was immediately seized with a sensation that went beyond their back-seat sex; it was the belonging she adored, the feeling of being a special sister or princess to all of the teen-center guys. But it was that willingness to please that triggered a series of events leading to Dobie's gang-rape at 15.

Dobie uses the moment as the pivot for The Only Girl in the Car. With every cigarette the teenage Kathy smokes and every halter top she ties on, we can see her barreling toward that awful night. Though there are many cathartic memoirs out there, Dobie's unbiased examination of the knotty, fumbling mess of young lust sets her book apart. Her recollection of wanting this vague, elusive interaction is so clear and immediate that it brings us back to our own fears and thrills. "I wanted boys, boys with light in their eyes, hoarse voices, hard arms, silky chests, bodies that were my size," she writes.

Young Kathy finds sexuality wonderful, yet she has no idea of its depth--or its wrath. Even though she goes around dressed like a Lolita and acting out on her impulses without reservation, it still comes as a shock to her when she realizes that, both at school and especially at the teen center, she's viewed as a cheap slut.

Though Dobie goes digging for the seeds of her frighteningly premature sexual revolution in her family life, she's not assigning blame to anyone. You get the feeling that she became sexually active at such an early age because she couldn't help herself. Her rape was not of her own will, but almost everything leading up to it was.

The Only Girl in the Car proves that not all girls who "go bad" do so out of ugly early traumas, but because curiosity drives them to. It's an ultra-intimate case study of a situation whose horrible climax had its roots not in an abusive home or a deep sense of rejection, but in an unexceptional set of circumstances and in the mind of a girl who could not help but find out how it feels to feel. --S.B.

[ North Bay | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

Buy one of the following from amazon.com:

'The Master Butchers Singing Club' by Louise Erdrich

'Reading Water: Lessons from the River' by Rebecca Lawton

'The Only Girl in the Car' by Kathy Dobie

![]()

Lit to be Tied

From the April 3-9, 2003 issue of the North Bay Bohemian.