![[MetroActive Stage]](/gifs/stage468.gif)

[ Stage Index | Sonoma County Independent | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Word Play

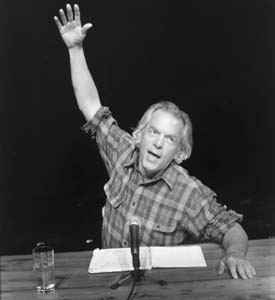

Shades of Gray: Monologue man Spalding Gray turns the bare stage into a "theater of the mind" with his deeply personal performances.

Monologuist Spalding Gray focuses on the future

By Patrick Sullivan

ONE OF THE FEW times I am not aware of time-slash-death--I equate them--is when I'm performing," explains Spalding Gray, his voice lingering on the word death a bit mournfully. "The other times are skiing and good sex. Those three pretty much hold up--they're my ecstatic states."

The actor, writer, and performer, speaking from his home in Sag Harbor, Long Island, pauses for a moment.

"If I didn't still have that in performing, that timeless moment at the table, I wouldn't have much impetus to go out there," he continues.

For some two decades now, Spalding Gray has reigned as America's master of the monologue, delivering his edgy, artfully confessional stories on stages across the country while seated comfortably behind his trademark wooden table. Along the way, Gray, who appears April 10 at the Luther Burbank Center, has also found time to build careers as an author and a movie actor. Perhaps best known for the Obie Award-winning Swimming to Cambodia--his 1987 monologue about the making of the Oscar-winning film The Killing Fields, in which he had a supporting role--Gray has also written the novel Impossible Vacations and appeared in such movies as Beyond Rangoon and Diabolique.

Monologues, however, remain the performer's main concern. These solo shows have been captured on film by such notable directors as Jonathan Demme, but Gray recommends seeing his work live. "There's a huge difference," he says. "The most radical act that I do, if you talk about my performances being radical, is being present as much as possible, going out on the road and being in the room. Because it's that 'being there' that establishes a rapport with the audience."

To the uninitiated, Gray's art sounds simpler than it actually is. In essence, he takes his personal experiences and brings them vividly to life on a nearly naked stage, weaving a web of words that pulls in everything from political observations to character studies to intimate scrutinies of his own emotional landscape. Gray is comic without being a mere comedian, dramatic without being a mere actor, and deeply compelling without needing a supporting cast or any more props than a glass of water, a microphone, and perhaps a map of Southeast Asia.

"It's theater of the mind in which, if it's working for the audience, they're imagining their own version of what I'm saying," Gray says.

His solo pieces, begun in 1979 and now numbering 19, have covered a gamut of deeply personal subjects, from the youthful experiences captured in Sex and Death to the Age 14 to the trying-to-write-a-book angst of Monster in a Box. Through all this work run Gray's grim fears about the passage of time: "Good morning," he once imagined his mirror saying to him. "You are going to die."

By comparison, Gray's most recent monologue sounds positively mellow. Morning, Noon, and Night focuses on a day spent with his family in their new home on Long Island. The piece chronicles the new life that Gray, now 57, began after his recent divorce, the far-more-harrowing tale of which he relates in It's a Slippery Slope, the monologue he will perform at the LBC.

Controversy over It's a Slippery Slope was perhaps inevitable. First of all, as Gray himself notes, the work marked a new direction in style.

"I think that where this is a watershed piece is that up until Slippery Slope I had always managed to get the audience to go along with me into a mother's relationship to a needy child," Gray explains. "So I was always crying out, 'Oh, oh, help me, I'm drowning. Look at me, look at what happened to me.' In Slippery Slope, I twisted it and said, 'Look what I did.' "

What Gray did was leave Renee Shafransky, his wife and his longtime collaborator, to marry a woman with whom he had been having an affair for many years. In the 90-minute Slippery Slope, Gray interweaves this experience with an account of his decision to lay aside his fear of death and plunge into downhill skiing.

The piece has generally won acclaim, but a few critics were outraged by what they saw as an artful attempt to excuse the performer's real-life bad behavior. To that criticism, Gray responds heatedly.

"But it's they who are excusing it," he says. "They don't have to. I'm not even sure what that means, because I'm taking blame for what I did. And I'm saying that in the piece. If I'm manipulating the audience to forgive me, then maybe I'm doing that and I don't know it."

All this confusion and confession may evoke images of television's cheatin' hearts pouring out their guts to Jerry Springer. Not surprisingly, Gray finds such comparisons distasteful, but he also thinks that what he deplores as the contemporary "culture of confession" is a bastardization of his own work, the artless product of a sort of reverse cultural evolution.

"I think the Monica Lewinsky interview [with Barbara Walters] was the apotheosis of what I started doing and what led into Jerry Springer and confessional talk shows," Gray says. "It's a very interesting cultural thing to observe, because it really has been the final blowout of any idea of privacy in America."

Indeed, Gray seems deeply disgusted by media coverage of the Clinton/Lewinsky scandal: "All I'm saying is that whatever that arc has been since the 1970s has reached its culmination in Barbara Walters' show," he says. "Barbara was a leering, prurient vampire. The only thing she didn't ask was, 'Could you fit it all in your mouth?' "

Partly in response to this disgust, Gray's own life and work have taken a new direction. For one thing, the eternal observer has now plunged into the local politics of his new hometown, where he moved after his divorce, to collaborate with local activists working to shut down a nearby nuclear power plant. His involvement is largely motivated by the fear that his children will be victims of what he calls "this very dirty plant."

His monologues, he says, are also changing. Gray's onstage persona has often seemed slightly adolescent, alternating between sly wit and wide-eyed innocence. With age and family has come a different attitude.

"I see an interesting growth that in some ways has paralleled my maturity as an adult," Gray says. "[My monologues] started out very innocent and distant. Now they've evolved into much more of the adult figure talking about his life. There's a lot more heart in them and less irony since I've had the children, and also a more sober adult voice, a voice that's talking about the emotion of loss and aging. They've gone from kind of adolescent to mid-range to a mature person."

[ Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Paula Court

Spalding Gray performs It's A Slippery Slope on Saturday, April 10, at 8 p.m. at the Luther Burbank Center, 50 Mark West Springs Road, Santa Rosa. Tickets are $18. For details, call 546-3600.

From the April 1-7, 1999 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.