![[MetroActive Stage]](/gifs/stage468.gif)

[ Stage Index | Sonoma County Independent | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Gotta Dance!

James Estrin

Modern-day movers come in all shapes and sizes

By Marina Wolf

I AM A FAT WOMAN, and I dance. This was not true 10 months ago. In my first day of cardio hip-hop class at a local gym, I left after 15 minutes and stood outside the classroom, staring in through the windows. Everyone in the class was thin, and the mirror was very, very wide.

Alienated and apparently alone, I joined a tradition of self-hatred grounded in several hundred years of Western dance aesthetic. At the intersection of fashion, cultural values, and real and imagined demands of dance technique, that inevitable full-wall mirror ensures that all but the thinnest, youngest, and most athletic are turned away from critical consideration and appreciation in the world of Western dance genres.

If your body falls outside those boundaries, you can expect at the very least stares from other dancers or verbal intimidation from a teacher. You may run into weight restrictions, unspoken but understood, or dance facilities with no wheelchair access. There are many ways to reinforce "the look." But they aren't working as well as they used to, because dancers of all ages, sizes, and physical abilities are taking their places on stage, and in front of that mirror.

Old Soles

A few dance leaders such as the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, the Limón Dance Company, and the Mark Morris Dance Group have made room in their ranks for older dancers. But most dance companies use the passage of time as an opportunity to replace older and still brilliant dancers with pliable youth who will do anything to meet a choreographer's artistic demands.

In the absence of widespread support, older dancers are creating their own venues for self-expression. The New Shoes Old Souls Dance Company offers San Francisco Bay Area dance professionals a chance every year to celebrate several hundred dance-years of experience that they bring to the stage. This year's performances packed the Cowell Theater in San Francisco, taking on traditional ballet and modern-dance merriment, with leaps, bends, and extensions that were no less heartfelt for being a little more moderate.

New Shoes director Linda Rawlings says older dancers still have much to offer--passion, experience, subtlety, character. Their disappearance into the relative obscurity of teaching, choreography, or administration, says Rawlings, deprives the next generation of dancers of a sense of history and the future. "Younger dancers often say to us, 'It's so great to know that we don't have to stop.' "

Acclaimed Sonoma County dancer and choreographer Ann Woodhead has danced seriously for 37 years. Now, at 59, Woodhead shapes her work to match her changing physical condition, but she has no plans to give up the art form she loves. (She'll appear locally in Spring Break, a collaborative improv performance at the Cinnabar Theatre April 8-24).

"There is a whole generation of dancers who aren't quitting," Woodhead says. "We haven't been quite as hard on our bodies, unlike earlier generations of dancers, and thanks to all the developments in sports medicine we're a lot smarter. So we're able to go on dancing longer."

A few organizations have sprung up to help older dancers stay in the life they love, such as Dancers over 40, a New York City-based organization that supports the artistic and career interests of older dancers and choreographers. The Dancers over 40 newsletter goes out to over 500 members in North America and Europe, who turn to it in search of the connection and involvement that they still crave. "You're always a dancer, whatever your age or whatever your physical capabilities," says co-founder Chris Nelson firmly. "Always. Because dancing is not the physical, it's the being."

In motion: 17-year-old Lissy Jenkins hits the dance floor in classes at the Sebastopol Center for the Arts.

The Kitchen Kut-Ups are living local testament to that idea. Dancers in the over-50 variety show spend much of their time on the slapstick side of jazz and tap, but their dance rehearsals at a Rohnert Park community center are serious affairs. Some of the dancers slide and kick their way across the dull gray linoleum in trios, while others mark moves near the kitchen in the community center. All of the dancers are over 50; many are over 65. But the scene is one that all dancers know, down to the sharp commands of the dance leader, Kay Mann. "Quiet, people!" she shouts as she walks around adjusting hand positions.

Meanwhile, director and founder Betty Ferra joins a visitor in flipping through photos from years past: a dancing nose, a row of can-can girls. Betty also points out a picture of her and her mother. "She danced until she was 89," Betty says proudly. "If she could do it, so can I."

Betty is one of the five octagenarians-to-be in the troupe; she's been running the show for 27 years, as it's evolved from a senior-center lark to six sold-out shows every summer in the Spreckels Performing Arts Center. They're practically pros. But dancer Helen McMaster has some advice for their well-wishers as she walks away after rehearsal. "Don't say 'Break a leg,' " she laughs over her shoulder. "That's the one thing that we don't say. Not at our age!"

On a Roll

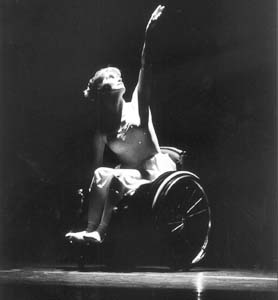

Of course, injury at any age can alter the course of a dance career, as New York dancer Kitty Lunn knows. In 1987, on her way to a Broadway tryout, she fell down a flight of stairs and became paralyzed from the waist down. Five and a half years passed before she danced again, in an improv performance assignment, but then the light bulb went on, as she puts it. "What I got at that moment was that the dancer inside me didn't know or care that I fell down a flight of stairs and broke my back and was now using a wheelchair," says Kitty. "She just wanted to keep on dancing."

Kitty returned to her balletic roots, which she found could be transposed onto the physical reality of wheelchair movements to achieve roughly the same artistic effect. But even with a new method, the road back was a long one. She desperately needed to get back into dance classes and culture, but the dance schools simply did not want to let her into conventional classes. One studio finally let her in on a probationary basis. "They were concerned that I would run into people with my wheelchair," recalls Kitty, "that I would hurt myself or hurt someone else, or disrupt the flow of the class.

"But it was really more than that. I [could see] their discomfort with the idea of having the wheelchair associated with the studio. When you think of professional dancers, you certainly don't think of wheelchairs. And they didn't want the stigma."

Kitty overcame that hurdle and went on to found the Infinity Dance Theater, a modern dance company that also includes older dancers. The group dances showcase Kitty's technique, as she slides and shifts her numb legs into positions of studied elegance, moving around the non-disabled dancers with ease. In the chair, her upper body arches and lunges with the best of them.

As Kitty points out, dancing sitting down is not a new concept. "Martha Graham did 'Lamentations' in the '30s. Ruth St. Denis was dancing sitting down 100 years ago. I have rollers on the bottom of what I'm sitting on, but they made it OK to sit down 100 years ago. So I am not alone in this."

Kitty has company in the modern day, too, as disabled dance troupes and integrated companies (those who have both disabled and non-disabled dancers) have sprung up around the country and the world, hot on the trail of the broadening disabled-rights movement. Disabled dance advocates estimate that at least a couple dozen professional and semi-professional troupes are in operation now, covering the genres from jazz, ballet, modern, and postmodern to even a traditional butoh group in Japan. The dance establishment has been slow to embrace the genre, but these dancers on wheels keep dancing.

Natural talent: Sonoma County dancer Ann Woodhead still has the moves.

On a recent Sunday evening, members of the Axis Dance Company are too intent on rehearsing a new move to be much distracted by the Bulgarian voice choir down the hall or the grimy industrial heater that releases a suspicious smell of sulfur. Guest choreographer Joe Goode watches from his stool at the side of the studio in south Berkeley as the chair dancers lean forward in their wheelchairs, supporting the standing dancers in a horizontal back-to-back balance before rolling them off to the side. A new move like this is one of the reasons that Axis loves to work with outside, non-disabled choreographers, says co-director Nicole Richter after the rehearsal. "They definitely come up with things that we wouldn't come up with."

Judith Smith, co-director and one of the company's founders, nods in agreement from her motorized chair. "They don't know what our limitations are. They don't know what our potential is."

With an inherently different physical structure, and different principles of balance and counterbalance, wheelchair dance brings a unique presence to the stage. And when the idiosyncrasies of wheelchair movement are factored in, the potential for new forms of dance is infinite. For starters, the wheelchairs, especially the motorized ones, enable dancers to remain in motion longer. A motorized chair is powerful enough to pull whole clusters of dancers across the floor. Uli Schmitz, a member of the company who uses both crutches and a chair to dance, brings up another feature of wheelchair dancing: "There are no tapping feet," he says in his quiet Austrian accent. "It's all smoothness and gliding.

"You see a lot of dancers trying to float softly, little tiny steps across the stage." He makes a slightly scornful tip-toe gesture. "But it's very easy in a chair."

Living Large

If the Western dance world has been slow to accept older dancers and dancers in wheelchairs, it has been positively glacierlike in welcoming people of larger body sizes. That honor belongs to various ethnic dances, which have retained an appreciation of body diversity while infusing the American dance scene with new energy and techniques.

The new paradigm is evident in Victoria Strowbridge's Tuesday night African dance class at the Sebastopol Community Center. A guy who brought in some free loaves of bread is jammin' around the edges, and off in the corner a new mother gently rocks her baby to the beat of the congos. But out on the floor, in steadily advancing rows, the dancers work their bodies in patterns that are both meaningful and demanding. In the middle of the second row, in the midst of the pulsing bodies, 17-year-old Lissy Jenkins is showing the application of more than a decade of dance training. Her wrists and arms move elegantly, flowing to the undulating rhythms; her hips tilt and sway with controlled energy. That she is the largest person in the room is incidental.

Lissy is philosophical about her participation in the dance. "Everyone has a different body and everyone moves differently," she says. "It's not about how big you are, it's how you work with it."

Not all of her teachers have been as supportive as Victoria, who experienced enough in the jazz and modern dance worlds to know how important a supportive teacher is.

"Lissy has a natural rhythm," she says enthusiastically. "Some people just have it, and some people have to work at it. Lissy has it." Not all forms of African dance have the same lower center of gravity as the Afro-Caribbean style she favors, says Victoria, but they all value passion, an "energy flow," as she puts it. "When you're tapped into that, there's support from everyone in the room," Victoria says, her eyes glowing. "When they see someone who is riding that energy wave, then all barriers fall away."

In the Western dance world, unfortunately, those barriers are still there. Though weight standards in professional companies have been abolished in theory, pressure remains high to keep the number on the scale low, especially in ballet. This pressure travels right down to the students as well, with potentially disastrous results: A late-'70s study of ballet students suggested that as many as 8 percent had anorexia (as opposed to between 1 to 2 percent of the general population of adolescent girls), and a full 45 percent had other disordered eating habits.

In this weight-obsessed environment, modern dancer Alexandra Beller--a self-described "hourglass with a lot of sand"--constantly struggles to establish herself as a full participant. Always large and, she says, always dancing, Alexandra has gotten flak from dance teachers and administrators for as long as she can remember. Nonetheless, only one year after getting her B.A. in dance, Alexandra was tapped for the New York-based Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company, a pioneering company that has long been known for its radical dance themes and technique as well as its physically diverse dancers.

While the step up gave her a place in one of the top companies in the United States, it also increased her exposure to critics and audiences that have sometimes been more interested in her dimensions than in her dance.

"One night this woman started going on and on about how amazing it was to see someone like me," recalls Alexandra with annoyance. She compares that comment to something that might have been said with all good intentions to a black doctor or lawyer 50 years ago. "I know we're not there yet, but I hope in 50 years somebody sees this as prejudiced and condescending, because I've got two arms and I've got two legs and a spine and a brain and 16 years of dance training. So why wouldn't I be able to do everything that these [other] people are doing?"

Alexandra feels fortunate that Bill T. Jones' approach to dance resonates so thoroughly with her own style. "Bill talks all the time about weight as a physical sensation. 'Feel the weight in this arm and then send the weight here, or feel your weight drop here.' " Alexandra hesitates, searching for words that explain the sensation. "I'm very in touch with the weight of my body, which gives me a real sense of being in the middle of my flow. ... I think that maybe it has helped me to feel like I am riding something that is rooted.

"But I love to fly, and I do that too," she concludes almost dreamily. "Leaps and things, yeah. I love to fly."

Beauty Ideal

I love to fly, too, but almost didn't. Hip-hop isn't modern dance, but it is submerged in the American cult of athletic thinness, so there's not a lot of room for the larger dancer in it. All the funky fashions stopped at size 12, and the videos I watched for inspiration all had that buff Janet Jackson thing going on. But somehow I stuck to it, and over the course of eight months moved from the back row to the front guard. Three months of extracurricular rehearsal landed me space in a talent show for a solo performance, shimmying my belly-baring red crop top (custom made, of course) to a fast jazzy number that got the audience on its feet after 30 seconds.

I'm taking dance classes at the community college now, where the average age and waist size of the dance students seem to be about 19. There are no dancers with visible disabilities in my classes, and only a few older people. A couple of folks fall on the plumper side, but none are as large as I am. Walking into that studio in a sports bra is exposing my belly, both literally and figuratively, to a dance culture that still desperately craves the Western beauty ideal.

Instead of turning my eyes away in embarrassment, I'm learning to look that ideal in the face. The wall-length mirror used to feel too narrow for comfort. But actually, in spite all the difficulties, it's wide enough to include everyone. Including me.

[ Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Reaching new heights: Kitty Lunn represents a new wave of artists overturning old conventions and revolutionizing the modern dance world.

Reaching new heights: Kitty Lunn represents a new wave of artists overturning old conventions and revolutionizing the modern dance world.

Michael Amsler

ISHA Star power: Betty Regan of the Rohnert Park Kitchen Kut-Ups struts her stuff.

Star power: Betty Regan of the Rohnert Park Kitchen Kut-Ups struts her stuff.

From the March 18-24, 1999 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.