![[Metroactive Features]](/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | North Bay | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

The God Problem

Breaking tradition to fix Christianity

By David Templeton

There is a sign affixed to the door of the Rev. Jerry Stinson's office at the First Congregational Church in Long Beach, Calif.: "Think for Yourself--Your minister may be wrong."

This succinct admonition says a lot about Stinson's church, where he has served as senior minister for five years, and quite a bit about Stinson, who has always encouraged the members of his congregation to do their own thinking on religious and spiritual matters, to trust their own intellects, to put their reason on an equal par with their faith. And the reverend believes that the Christian world at large would be much better off if more of Christianity's adherents were encouraged by their clergy to do the same thing.

Stinson is not alone.

"There are many, many progressive communities within Christianity today," he says. "These are groups that are trying to walk in the legacy of the historical Jesus, that are being taught to value religious literacy and intellectual truth, and that are working to develop a powerful, meaningful progressive faith."

Stinson will be in Sonoma County on March 2 to deliver the opening-night address at the annual four-day spring meeting of Santa Rosa's controversial biblical think tank known as the Westar Institute. Established by Dr. Robert Funk in 1986 as an advocate for biblical literacy around the world, Westar is also the sponsor of the Jesus Seminar, an ongoing project in which liberal Biblical scholars, teachers and theologians gather to take a hard, open-minded look at the historical accuracy of various pieces of the New Testament. As a result, the seminar has produced volumes of research challenging the Christian community at large and motivating theologians and churchgoers to make up their own minds about who Jesus is, or was, and what he really said.

This year, Westar's spring meeting kicks off with a series of lectures, workshops and panel discussions on a variety of topics ranging from the challenging ("The God Problem: Options for Making Sense of Christianity") to the inspirational ("Moral Issues in the Aftermath of 9/11").

A stellar assembly of guest speakers, including such prominent religious thinkers as Don Cupitt, Robert J. Miller, Arthur Dewey, Nigel Leaves, Paul Alan Laughlin and filmmaker Paul Verhoeven (Showgirls and Robocop), will present the various lectures and panel discussions. Verhoeven (yep, he's a Biblical scholar--deal with it) will host a Saturday afternoon forum to discuss his scholarly papers examining such esoteric New Testament minutiae as Jesus' emotional relationship to lepers, the parable of the Good Samaritan and Jesus' last cup of wine on earth. All events are open to the public.

The seminar's detractors--most from among the evangelical minority of modern Christians, who believe that every contradictory word of the Bible is resoundingly true--claim that the Westar scholars are hell-bent on destroying Christianity. In the minds of those same scholars, however, the Rev. Stinson included, what they are really attempting to do is fix Christianity, which many of them see as a fractured, dysfunctional, yet intrinsically beautiful religion that has strayed too far afield from what its inspiration, the historical Jesus himself, was talking about all those years ago.

Stripping away 2,000 years of mystical mumbo-jumbo, digging beneath layer after layer of Church-sanctioned dogma and medieval spiritual spin, the scholars of the Westar Institute have led the way--now being taken up by a growing number of progressive faith communities--to building a faith around Jesus the man, rather than Jesus the myth.

"I think there's a fairly clear notion now of who Jesus actually was, an idea of Jesus that is separate from a great deal that the early church said about him," Stinson says. "My question is--and I'll be talking about this in my presentation--if we take that historical Jesus and try to live out his legacy, what would that make the Church, as a faith community, look like?

"I think that the life of the historical Jesus, in which Jesus is a very human figure, points us in the direction of God," he continues. "I don't think Jesus was God, but I think that when we look at the life of the historical Jesus we can get some incredible insights into the nature of the divine, and gain insights into what it is that makes life meaningful. I don't think Jesus has to be God to do that. I think Jesus is one of a number of lights that illuminate the divine for us: the Buddha and Mohammed and other religious figures are also lights and guides toward the divine. I find the historical Jesus to be the best guide on my own pathway to the divine--but it's certainly not the only pathway, and Jesus is certainly not the only guide."

Nigel Leaves, who will be leading the "God Problem" workshop, is dean of studies at John Wollaston Anglican Theological College in Perth, Western Australia. He's the author of Odyssey on the Sea of Faith, and the upcoming Surfing on the Sea of Faith. He agrees that the scholars of the Jesus Seminar are not out to break Christianity--the early Christians already did that.

"Christianity has always been 'broken' in the sense that it has always had more than one way of interpreting the life of Jesus," Leaves says. "The Gospel accounts are responses to the question, 'Who do you say that I am?' Each of the Gospel writers--and, indeed, St. Paul--give variations as to who that might be, from 'son of man' to

the divine logos. Throughout the history of Christianity, there have been various groups who have encompassed a wide spectrum of belief. Unfortunately, the history of Christianity has been written by those who have triumphed orthodoxy. When you actually read ecclesiastical history without the lens of orthodoxy, it is a far more disparate story than is given credit."

That said, Leaves is not certain Christianity can ever be fixed.

"If by being 'fixed,'" he says, "Christianity is to be the same all over the world, then it is broken. However, if great variety [within the Church] is permissible, then I'd have to say that Christianity is not broken at all. If we, in the Church, would actually begin with affirming humanity and its wonderful diversity, rather than the usual list of negatives, then Christianity would be seen as a more attractive proposition for people."

The diversity that Leaves refers to encompasses all of humanity, all of Christianity and all of the world's numerous religions. Still, Christianity, for centuries, has identified itself as "other than"--and usually "superior to"--other religious belief systems. Some of the Westar scholars believe that what Christianity needs most is a good dose of reality, in terms of its own history and its relationship to other forms of faith.

Paul Alan Laughlin, professor of religion and philosophy at Ohio's Otterbein College, is the author of the forthcoming book Getting Oriented: What Every Christian Should Know about the Eastern Religions but Probably Doesn't (Polebridge; $20). At the Westar meeting, Laughlin will present "Getting Oriented to Enlighten the Christian Faith." Like the Rev. Stinson, Laughlin also has a sign on his office door, a bumper sticker proclaiming, "God is too big to fit into any one religion."

"My experience as a college professor," says Laughlin, "is that the students coming to me out of a variety of Christian backgrounds have one thing in common, and that's that they know very little about their own faith: they don't know an apostle from an epistle, can't explain the difference between the Old and New testaments, and have no sense of what the distinctive doctrines of their faith are compared to other world religions. They know nothing about the other religions of the world. I think that's tragic. But then, as a teacher, I'm biased. I believe that knowledge is always better than ignorance."

Laughlin asserts that this is an important message in a world where radical Christian fundamentalists equate any and every nonevangelical Christian faith (including all non-Christian religions and a number of Christian expressions such as Catholicism and Presbyterianism) with evil. According to Laughlin, history proves that Christianity would not be Christianity were it not for other belief systems, and that one way for modern Christianity to heal its fractures would be to start taking a look at other faiths again.

"Christianity has a long history of going outside its own comfort zone to find treasures in other philosophies," Laughlin says. "Christianity, for example, reached out to Greek philosophy early on to understand what Jesus was and what he was about. That's a process I think that needs to be ongoing. I'm an advocate of looking outside of Christianity, specifically to the three great Eastern traditions--Hinduism, Buddhism and Taoism--and finding resources there that my help us rethink and refashion Christianity into a more plausible faith for the 21st century."

[ North Bay | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

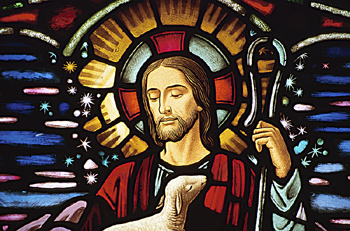

Christian, Right?: Perhaps Christ-based religion needs to define itself by what it is, not by what it's not.

The Westar Institute's spring meeting is slated for Wednesday-Saturday, March 2�5, at the Flamingo Hotel. Fourth Street and Farmers Lane, Santa Rosa. $10�$300. 877.523.3545. www.westarinstitute.org.

From the February 23-March 1, 2005 issue of the North Bay Bohemian.