![[MetroActive Dining]](/gifs/dining468.gif)

[ Dining Index | Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Shelf Life

Local chefs collect cookbooks for inspiration and guidance

By Marina Wolf

WHEN FAMILY or friends come over for the first time, their eyes inevitably go to my cookbooks. I don't mind. If I did, I wouldn't have lined all 200 of them up in a 7-foot-high bookcase in the living room. I'm proud of the books I've accumulated over the years, from my first, a battered copy of the Moosewood Cookbook, to my latest acquisition, a shiny new book on foie gras (that I will probably never use). And yet, when visitors gasp and make astonished noises, honesty and modesty compel me to say, "Some people have a lot more cookbooks than this, you know."

People like Bea Beasley, for example, a Santa Rosa caterer whose collection has passed the 3,000 mark. "I don't think there's a bad cookbook," she says in defense of her addiction. "You can learn from the worst books."

Beasley's collection might be considered a little extreme--most collections that size are in libraries or have cooking schools attached--but only in scale, not in the impulse.

The food world is full of people who turn to cookbooks to learn, to research, to be inspired.

If that sounds hifalutin, it's not. While ordinary cooks tend to pick up a few books and follow the recipes slavishly, cookbooks are simply required business reading for most food professionals. Christina Brenner refers to her collection weekly at least. "I try to become aware of what's out there through my students, when they look at chefs and magazines to pick up patterns," says the Simi Winery chef and instructor at the California Culinary Academy. "But I need cookbooks to keep up with them and with my own menu development."

Brenner bought her first books, La Technique and La Méthode by Jacques Pepin, when she suddenly found herself in business as a chef in 1977. "I needed to bring my skill level up as quickly as possible, but I couldn't afford cooking school."

Since then, of course, Brenner has gotten enough of her own experience, but she remembers those two tomes fondly as helping her onto the first step.

THESE DAYS consumers are going for the glossy, personality-driven titles that you might hear about first from the companion series on Saturday-morning PBS cooking shows. These books have lots of pictures, so they even read like a TV show. In contrast, most chefs will focus on information-filled items from well-known names, the classics of the genre: Robuchon, Trotter, Child. Chef John McReynolds of Cafe LaHaye in Sonoma stocks up on what might be considered the new American classics, by such chef-authors as Joyce Goldstein and Paula Wolfert. In reality, McReynolds visits his bookshelf, which he estimates holds well over 200 volumes, maybe a couple of times a month. But he'll spend a whole afternoon just browsing, looking for touchstones, an ingredient or technique or idea.

It's an immersion workshop with the authors, many of whom he knows only through their recipes. "In lieu of working with them, I can glean information from all of these chefs through their books," says McReynolds.

Well chosen and in large enough quantities, cookbooks constitute an important reference source. Emily Schmidt, a private chef in Napa County, fields several calls a week from friends who are looking for culinary information and know that she has the materials to help. She also turns to her books to cross-reference.

"I can get five versions of a recipe to check it out and see which one works best," she says.

Angie Lewis, co-owner of Chez Marie in Forestville, even turns her 1,800-volume library over to customers, encouraging single diners to browse the shelves for dinnertime reading. "I use cookbooks to answer questions a lot," says Lewis.

"When customers ask what cassoulet is, and I have time, I'll go get them a book and they can read about it for themselves."

Lewis' partner and the chef at the restaurant, Shirley Palmisano, hardly ever opens a cookbook, relying instead on Lewis to supply her with information, which Lewis is usually able to locate quickly, thanks to her self-designed shelving system.

Research questions aside, though, most chefs simply use their books to prime the pump. Gary Jenanyan, executive chef at the Robert Mondavi Winery, has been cooking professionally since 1971; at this point, he says, his cooking is mainly intuitive. But occasionally the well runs dry: "Sometimes I'm just brain-dead. I don't know what to cook."

At such moments, Jenanyan sits down with his 300 or 400 cookbooks. He has an additional source of inspiration in a set of cook booklets compiled from visiting chef participants in the winery's Great Chefs program.

AS MANY TOMES as these chefs have, you'd think that their first books would have crumbled to dust or faded into oblivion by now.

After all, culinary arts have moved on, haven't they?

But it takes only a little thought, and maybe a quick rummage, for most cookbook connoisseurs to remember their first books; often, they're still using those books decades later.

Schmidt has kept several seminal books in active use, books that at first glance seem hopelessly out of date. She has the original Time-Life series of cookbooks; the 1954 edition of the Ladies Home Companion Cookbook that came as a freebie with a set of encyclopedias--the encyclopedias now are thick with dust, but she still uses the cookbook.

Then there is the Woman's Day Encyclopedia from the '60s.

Schmidt recently bought another copy of the latter for one of her daughters, who expressed her thanks in a manner that any cookbook fan can appreciate: "I thought I'd have to wait until you die to get a set like that."

[ Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

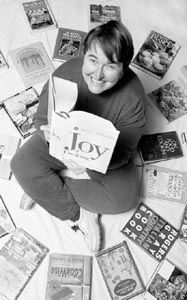

All lit up: Angie Lewis, co-owner of Chez Marie, sometimes turns her 1,800-volume collection of cookbooks over to interested customers.

All lit up: Angie Lewis, co-owner of Chez Marie, sometimes turns her 1,800-volume collection of cookbooks over to interested customers.

From the February 17-23, 2000 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.