![[MetroActive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

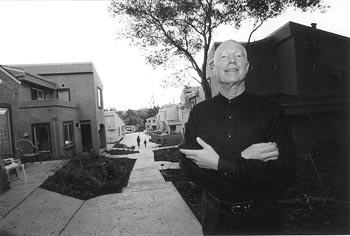

One alternative: Michael Black, an architect by trade, helped initiate Two Acre Wood, an intentional housing development that opened last August in Sebastopol. The project, says Black, is based on sound humanistic principles.

A Different Path

Intentional communities gain a foothold

By Yosha Bourgea

MICHAEL BLACK is not a guru, but he looks like one. From the Taj Mahal gleam of his bare scalp to his attentive gaze and calm, well-considered speech, his appearance evokes a sense of harmony that is reflected everywhere in his self-designed home near downtown Sebastopol.

A wide arch above a counter defines the boundary between kitchen and living room without the presence of a wall. Around the perimeter of the main space, a row of small, square windows above eye level brings in daylight without sacrificing privacy.

Behind the house, a redwood deck leads out to a hot tub. And from the front door, a paved footpath leading down a slope connects to the other homes in the new intentional community of Two Acre Wood.

The only flaw in this otherwise serene picture is one that Black, an architect, did not design. Just a few yards up the hill, on the other side of a low fence that marks the edge of the lot, a row of identical beige houses rises like a wall above the oak trees. This is Stefenoni Court, a conventional housing subdivision that dominates the western horizon.

The tenants of Two Acre Wood began moving in last August, and already the community has seen the death of a dog and the birth of a child. Despite a storm of protest from neighbors concerned about the impact of traffic on their quiet road, Black, the initiator and designer of Two Acre Wood, succeeded in persuading the Sebastopol City Council to approve the zoning for the site.

Now the community of 25 adults and nine children is working to establish positive relationships, both internally and in the greater neighborhood. There also are plans, Black says, to plant vines along the western fence to block the view of the subdivision next door.

But there's no concealing the fact that, like all intentional communities, Two Acre Wood is still an exception--an island in a sea of tract housing.

THE ORIGINS of the term "intentional community" can be traced to circa 1950, according to the website of the Fellowship for Intentional Community. Definitions are as abundant and diverse as the people who live in places like Two Acre Wood, or Monan's Rill in eastern Santa Rosa, or the Sowing Circle west of Occidental.

While most agree that an intentional community consists of a group of people sharing land or housing in a cooperative spirit, there are myriad ways that such a group can be structured. From private would-be utopias and religious enclaves to public-service-oriented groups and co-housing developments, the movement toward intentional community is growing.

The FIC website lists almost 100 such communities in California alone--and those are only the ones that requested to be on the list.

The site estimates that there are several thousand others throughout the country.

For those unfamiliar with contemporary intentional communities, the image of a hippie-laden commune is often the first to come to mind. Communitarians do tend to be left of center politically, and some have roots in the counterculture of the '60s and '70s; Black's wife, Alexandra Hart, was a founding member of the controversial Morningstar Ranch in Graton. But the raucous, laissez-faire ambiance of such places has proven difficult to sustain, particularly from a financial standpoint.

The rallying cry at the now-defunct Wheeler Ranch commune was "No Rules!" But today, few of the people who can afford to invest in home ownership in Sonoma County would be willing to chant that particular mantra.

ALTHOUGH A SHARED ethos is central to most intentional communities, another factor drawing many people to consider participation is the economic advantage of community living. "What you tend to see more of around this area is highly enlightened real estate deals," says Mary DeDanan, one of a group of people working to establish a small intentional community near Jenner.

"If you look at what median housing goes for versus what we're offering, it's pretty affordable."

Prospective members of Wild Iris Ranch, must pay a $1,000 nonrefundable "earnest money" fee to show the seriousness of their commitment to join. That fee is part of the down payment, which is $15,000 for a single member and $20,000 for a couple. At buy-in, the membership is $105,000 (including the down payment), with monthly mortgage payments expected to average $900.

Compare that to the conventional market, where the median resale price last year hovered around $255,000 for a house or $140,000 for a condominium, and intentional community starts looking like a pretty smart idea. Of course, not everyone would be comfortable with the cozy living situation at Wild Iris Ranch.

"We're taking the housemate concept to the nth degree," DeDanan says. "A lot of people don't want that."

To comply with rural zoning laws, which allow just one house plus a granny unit per 40 acres, DeDanan and fellow core-group members Marcin Whitman and Chris Carpenter are designing a community that is a hybrid of co-housing and shared housing.

In addition to a single-bedroom granny unit that is already finished, the group plans to build a large structure, incorporating three to four separate bedrooms, around a common living space. Because the building will have only one kitchen, it can be legally defined as a single house.

"People want their own little piece of property," DeDanan says. "[But] the individualistic model, with 50 little houses each with their own washer and dryer . . . the planet can't sustain this kind of stuff."

Michael Black agrees. "We're founded on humanistic and ecological principles," he says. "We live closer, more modestly, to not use up the surface of the planet for housing.

"We should not live isolated lives."

IRONICALLY, many intentional communities find it necessary to isolate themselves from mainstream society in some way, if only to preserve their sense of integrity. Some are cautious about revealing their location or welcoming visitors who are not familiar with the priorities of the group. Concern over the possible impact of this article on a precarious relationship with neighbors also led one community member to request "vague" descriptions.

Monan's Rill, one of the most firmly established intentional communities in Sonoma County, has survived (and thrived) for a quarter of a century by protecting the privacy of its residents.

"When we first came here 25 years ago we were a little overwhelmed, and we tried not to have too much notice paid to us," says Russ Jorgensen, one of the founding members.

"Now that we're a mature group and more stable, we don't mind having visitors when we can be helpful."

Still, when an unknown reporter requests a visit, Jorgensen says he'll need to talk it over with the other residents at a general meeting before he can give a definite answer. Like many intentional communities, Monan's Rill governs by consensus, a process that is less impersonal but more time-consuming than majority rule.

The need of the community to deliberate openly is crucial, an outsider's deadline notwithstanding.

"There's a stance of using consensus that is inherent in co-housing," says Black of Two-Acre Wood. "It's not about the power of the majority."

A common problem within intentional communities concerns the division between private and public space, and the balance between individual freedom and community standards. As a new community, Two Acre Wood is just beginning to address some of these issues. Some residents, Black says, consider their front porches private space and use them for storage. Others see this as a disruption of the neighborhood's unified look. But as with any other conflict, a resolution will come when all the neighbors sit in a circle, speaking honestly to one another and listening with respect.

"Consensus is the glue that holds us together," Black says.

[ Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Photograph by Michael Amsler

New College of Santa Rosa (99 Sixth St.) will host "Finding and Financing an Intentional Community," a forum introducing the skills needed to start a co-housing project, on Saturday, Feb. 12, from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. The cost is $100. Call 568-0112. Meanwhile, a new co-housing group is enlisting participants for a planned community in downtown Cotati. For details, call Geof Syphers at 510/891-0446.

From the February 10-16, 2000 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.