![[MetroActive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Sonoma County Independent | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Mercury Rising

Michael Amsler

Abandoned mercury mines leave toxic legacy in North Bay

By Janet Wells

MERCURY--with a mythological cachet of fleet-footed skill, and synonyms like "quicksilver" and "cinnabar" gracing the names of local restaurants, schools, and theaters--is part of Northern California's heritage. The sinister era of mercury may be over--people no longer regularly go insane from working with highly toxic mercury liquid or strip-mine the coastal hills for mercury ore.

Yet, few people even know about the old mercury mines hidden in the hills of Sonoma and Marin counties, the processing buildings and sheds abandoned to rust, dilapidation, and weeds.

But mercury waste, hundreds of thousands of cubic yards of tailings thrown into the deep gullies and ravines, is very much part of the present, flowing into streams and showing up in fish and wildlife at alarmingly high levels. An intensive $3 million cleanup effort is nearing completion in northern Marin County, where, in a steep canyon, 200,000 cubic yards of mining waste containing 590,832 pounds of mercury have been eroding into Gambonini Ranch Creek, which drains into Walker Creek and, about 10 miles downstream, Tomales Bay.

While commercial Tomales Bay oysters--grown on racks or in bags above the sediment where mercury settles--are well within safe limits, research on native shellfish, along with other fish and birds, tells a different story. The Gambonini Ranch mine site "poses a significant threat to the beneficial uses of Walker Creek and Tomales Bay," according to a new report by the San Francisco Regional Water Quality Control Board. The report also warns of a "potential threat to humans and wildlife."

Says Tom Baty, an Inverness resident who has been fishing Tomales Bay for 40 years, "The possibility that there is mercury bio-accumulation that people are eating is of great concern. It's a tricky question to be asking oneself, but if there's a problem with the local fish, it's better that we all know."

Farther north, at the headwaters of the Eel River, a source of water to the Russian River, officials from the North Coast Regional Water Quality Control Board have found elevated levels of mercury in freshwater bass. The probable cause, according to senior engineer Bob Tancreto, is underneath Lake Pillsbury, where a town with a mercury mine was abandoned and buried in the early 1900s when the Cape Horn and other dams were built to create the reservoir.

In Sonoma County, a mercury mine similar to the Gambonini site's ore extraction and processing, caused consternation more than 15 years ago. Construction of the Guerneville sewage plant used mercury-laden tailings in soil and gravel from an abandoned mine at Mt. Jackson for road base material. After extensive tests, county health officials found nothing alarming about the inert reddish dirt, and Tancreto says that waste from the Mt. Jackson mine--which likely is washing down into Fife Creek and on to the Russian River--"is not an issue."

"If you take a sample of soils anywhere in this county, you will find mercury in it, but in the form of oxide, so it's not a dangerous element," he says.

However, testing of creeks and wells in the Mt. Jackson mine area was last done 15 or 20 years ago. "Whether it deserves another look is a good question," Tancreto concedes.

MERCURY CAN BE a nasty substance. Liquid mercury, which can be absorbed through the skin, leads to insanity and death, as in the "Mad Hatters" who used the chemical to form felt for hats. The ore form of mercury mined in California was processed using high-temperature ovens. The waste from ore processing becomes a threat to humans when it stews in an anaerobic environment like water and transforms into an organic substance that "bio-accumulates," coming up through the food chain and causing long-term health problems, especially in pregnant and nursing women and young children.

Mercury, along with dioxins, pesticides, and PCBs, is a known health issue in San Francisco Bay, where fish advisories are posted, warning what kind and how much fish is safe for consumption. In contrast, Tomales Bay, the long thin estuary nestled among coastal rolling hills just south of the county line and feeding into Bodega Bay, is considered a clean-water haven.

"It's a big issue, because the bay is so clean, relatively speaking," Baty says of Tomales. "No one thinks about any problems here."

But maybe they should. Last year, a study on heavy metals accumulating in Suisun Bay ducks from agricultural runoff was published in a national science journal. Tomales Bay ducks were to be the "clean" control group for that study until scientists found that the Tomales birds had twice as much mercury as those in the Delta--levels high enough that "over winter survival and reproductive successes are at risk," according to the water board report.

"That was an eye opener for us," says Dyan Whyte, associate engineering geologist for the San Francisco Regional Water Quality Control Board and head of the Gambonini site cleanup. "From a statewide perspective, it is a relatively small mine, but when we looked at the amount of mercury [washing down from the site], it was a very high amount and going into a very pristine water body."

Whyte spent two winters slogging out to the remote Gambonini mine site, often in the middle of the night, to gather data on how much mercury was traveling from the waste pile into the water system. "We found that discharge was very tied in to storm events," she says. "If I'd gone in the summer or even once a week, I might not have found anything. It's a very different picture if you go out when it's raining. Eighty percent of the mercury left within 20 percent of the time."

The big El Niño storms last year and in the early '80s only made the downstream contamination worse. In 1982, a dam made of mine tailings failed, inundating the creek below with mercury waste. Last January and February, the mine site released an "alarming" 170 pounds of mercury to downstream waters, according to Whyte's report, about one third of the amount that the entire Central Valley releases to the San Francisco Bay in a year.

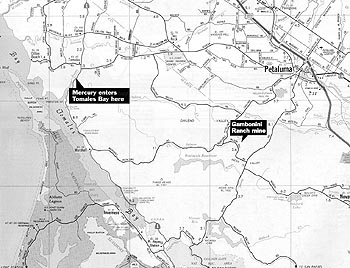

Poison path: Mercury is washing out of the Gambonini Ranch mine site into Walker Creek and then flowing west into Tomales Bay near the county line.

LEGALLY, environmental hazards are the responsibility of the property owners or the polluter. In the Gambonini mine case, the property owners don't have funds for cleanup, and the mining company that leased the property is long gone.

Property owner Alvin Gambonini, who suffered a stroke in 1997 and has difficulties speaking, grew up on the 1,400-acre cattle-grazing-ranch. Gambonini, 76, and his 64-year-old wife, Doris, lease most of the property to cattle grazers, keeping enough land for their 26 cattle, seven sheep, and a ramshackle ranch compound, with sheds, pens, bales of wire, and even a cast-iron clawfoot bathtub out front.

The mine site, leased to the Buttes Gas & Oil Co. by Gambonini's parents, is across Wilson Hill Road from the ranch house six miles southwest of Petaluma, and up a steep ridge. The Gamboninis used the site's deep canyons as a dumping ground for old cars and tires.

"We didn't know too much about it," Doris Gambonini says of the mine. "We felt like there wasn't any problem at all."

Buttes Gas & Oil operated the mine at Gambonini Ranch from 1964 to 1970, when the price of mercury plummeted and all but killed the ore-mining industry. In 1985, Buttes Gas & Oil filed for bankruptcy, and in a federal bankruptcy court settlement the state agreed to release the company from liability in exchange for $128,000 to be used toward remediation of the site. Cleanup of a 15-acre unstable pile of mine waste had a significantly higher price tag than the amount wrested from the bankruptcy court, and the state didn't want to take on the cost or the responsibility, since, legally, whoever cleans up a site is then liable for it.

Eventually geologist Whyte, armed with findings showing levels of mercury high enough to qualify as an emergency, secured $2.5 million in federal funding through the Environmental Protection Agency. The state is kicking in about $500,000 for non-remedial portions of the project, thereby avoiding future liability.

The six-month cleanup removed the enormous tailings pile, replaced it with about 400,000 cubic yards of dirt, and built creekbeds 30 feet higher than the original gullies and filled them with 201,000 tons of rock to stabilize the slope. The hillside now looks almost manicured, terraced with drainage culverts and sausage-shaped straw "wattles." A nursery in Napa is growing 5,000 plants from seeds collected from the surrounding hillsides to plant on the new slope. About 100 willow cuttings were pounded into the center of the slope, where they will sprout into trees that soak up water from the slump-prone area.

"It's not for aesthetics, but for long-term stability," Whyte says of the plantings. "The goal of the project is to eliminate the release of any sediments from the site."

The land is, for all intents and purposes, permanent open space, since the state will not allow anyone to use or live on the contaminated property. The site will be fenced off, and warning signs posted.

While the Gambonini mine cleanup effort will go a long way toward cutting off the mercury flow at the source, the amount of mercury still in the ecosystem is unclear. "It will become less available if it is covered up with clean sediment or washes out to the ocean," Whyte says. "But how long it is going to take for it to flush through the system, we don't know. There still is mercury coming through the Delta into San Francisco Bay that is associated in part with mercury used during the Gold Rush."

In August, the state began studying fish in Tomales Bay to determine mercury levels, which at least preliminarily are highest in shark. A sizable Hispanic population has discovered shark fishing in Tomales, both for recreation and as a source of protein, says Baty, who has been helping the state with its research by providing samples of leopard shark, halibut, jack smelt, and other native fish.

"If the sharks they are consuming are a large proportion of their protein, there conceivably could be major health consequences," says Baty, who is concerned that the amount of the sport fishing--and therefore the amount of mercury consumed--may be underestimated in Tomales Bay.

"Fish and Game has no idea of how big it is here, how many people have been fishing, how many fish are landed or where they are going. There's no way of monitoring it," he says. "They should know so they can manage it."

The state's findings on Tomales Bay fish will go to the state Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, which issues health advisories through the media and works with county health departments to post warning signs or distribute flyers.

FOR SEVERAL YEARS, Tomales Bay oyster growers have endured mandatory closure of harvesting owing to septic and sewage flow into the bay during heavy rains. There are currently no warnings or advisories about mercury poisoning in the bay.

Drew Alden, owner of Tomales Bay Oysters, which cultivates about 200,000 oysters each year for sale at a local retail outlet, talked with Whyte about the Gambonini mine several months ago, and is confident that his shellfish are safe. But even if the levels of mercury are low in commercial shellfish, any allegations about environmental problems in the bay can be tough to combat, he says.

"People look at that and say, 'I don't want to eat those oysters, they have mercury in them,' " he says. "But I'm an advocate of educating the public. Mercury is a naturally occurring mineral. If there were no mercury mine up there, we would still have mercury. The question is, How much mercury is there to cause alarm?

"If there's enough, people should be aware of it."

[ Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Heavy-metal fan: State engineering geologist Dyan Whyte spent two winters slogging through the mud around the Gambonini Ranch mercury mine to gauge the rate of runoff from the contaminated site into Tomales Bay.

Heavy-metal fan: State engineering geologist Dyan Whyte spent two winters slogging through the mud around the Gambonini Ranch mercury mine to gauge the rate of runoff from the contaminated site into Tomales Bay.

CSAA

From the January 28-February 3, 1999 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.