Last Days of the Ark

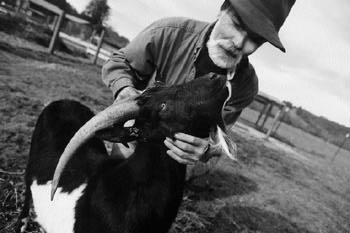

One World, One Beast: Ranch manager Serge Etienne tends to a rare goat at C. S. Fund's farm facility in Freestone.

Common livestock breeds are vanishing at a rapid rate. The few strains the world depends upon for food and clothing belong to a few corporations.

By Kelly Luker

There is a battle being fought. Although it rarely, if ever, has made the evening news, it is a war that all but a very few are guaranteed to lose. The battlefield? Look no further than your morning breakfast of scrambled eggs, toast, and glass of milk. The conflict rages around the newest eco-buzzword--biodiversity--and who owns God's handiwork. If biotechnical companies continue undeterred, our food sources will be neither God's nor nature's, but the property of Ciba-Geigy, Royal Dutch/Shell, Sandoz, or one of the other half-dozen multinational chemical corporations.

Welcome to the real One World Order.

NESTLED IN THE ROLLING HILLS a few miles from the Sonoma County coast, the little town of Freestone could be a postcard for rural living. About five miles west of Sebastopol, the handful of homes, volunteer fire department, and country store that compose this village hinges on a two-lane road, generously named "highway," that snakes through the pastures and farms of Sonoma County. The silence is deafening, sometimes punctuated only by the scraws of turkey vultures that glide effortlessly above.

Although Freestone's population hovers around 60, it is still quintessentially Californian, claiming an espresso stand that opens at 6 a.m. and a quaint bed and breakfast. It is also home to the C.S. Fund and its executive director, Martin Teitel. Both are dedicated to prodding an already disaster-numbed world to recognize this latest crisis that threatens our future food supply.

Teitel looks like a man who would be comfortable on a farm, which is a good thing, since that's one of the Fund's many objectives. First, however, explains Teitel as he relaxes in the den of this nondescript building, the Fund is a philanthropic organization of the heirs of C. S. Mott, one of the founders of General Motors. The heirs distribute about $1 million annually to carefully selected organizations dedicated to preserving two ideals held dear by Americans--the environment and the right to dissent. But we are here today to talk about the former cause and what may be Teitel's driving passion--preserving biodiversity.

To that end, his workplace is more than the Fund's office. It is also home to "walking gene banks," as Teitel calls them, livestock that are on the verge of extinction. For Teitel, a philosophy major who has been with the C.S. Fund since 1981, this is much more than a job: it is a calling.

He lives with his family next door--"a short commute," he laughs--and spends much of his time writing and publicizing his research and concerns about biodiversity. What makes these vanishing breeds on his farm so fascinating is their very ordinariness. As the world focuses on the disappearance of such exotics as the ocelot, elephant, and meercat, it is the many breeds of domestic livestock--like pigs, cows, and sheep--that are rapidly approaching extinction, creating a economic and social disaster in the making.

Teitel will be the first to tell you that people would eventually survive without the meat and dairy products these animals provide. But the critically endangered breeds of goats, sheep, and chickens that live here mirror the story that is unfolding with grains like barley, wheat, and rice--three crops that provide 75 percent of the world's food. Explains Teitel, "For the past 150 years or so, we've applied the industrial mode to agriculture."

Enthusiastic scientists have worked to develop a steady supply of uniform, high-quality goods--large white eggs, lean pork meat, lots of beef on the hoof. One by one, livestock breeds shrink or disappear, no longer needed by a population that they are dependent upon to survive. But Teitel's concerns aren't just nostalgic. The cost of these lost and threatened breeds promises to be devastating.

We wander out to the back pasture, where a San Clemente Island goat named Uno frolics with his friend, a more common Alpine breed named Dos. A couple of freckle-faced Navajo-Churros wander up to sniff inquisitively at Teitel's clothes. Bending to scratch the ram between its curling horns, Teitel explains that breeding these creatures is a double-edged sword. Any farmer will tell you that production traits (rapid growth, milk production, and meat conformation) respond quickly to selection pressure, while adaptability traits (reproductive fitness, climate tolerance, and parasite resistance) take a fair while longer. On the road to creating a "super producer," the qualities that makes the animal hardy are bred out, compensated by massive amounts of antibiotics and chemically enhanced feeds to counterbalance its frail constitution.

Now the problem is twofold: not only are animals more susceptible to illness, but there are fewer breeds to rely on if disease wipes out a particular strain.

As an example, Professor Bill Heffernan of the University of Missouri's Department of Rural Sociology, points to the domestic turkey that appears on dinner tables each Thanksgiving. "We found that in 90 to 95 percent of turkeys produced worldwide, the genetic stock comes from one of three breeding stocks," he says. These birds have been genetically altered to create breasts so large (for the favored white meat) that they are unable to breed naturally and must be artificially inseminated. "It's only a matter of time before we end up with some disease that, with this narrow genetic base, we have no resistance to," Heffernan says.

This situation is, of course, not limited to turkeys. Virtually all--95 percent--cows' milk comes from one breed, the Holstein-Friesian. About 60 percent of those dairy cows can be traced to only four breeding lines. And, those morning eggs and sausage? Nine out of 10 eggs come from the White Leghorn, while 25 to 30 percent of the hogs that provide the "country links" come from only six breeding lines.

IF THE LACK of diversity in gene pools is disturbing, to get very nervous one need only look at how just a few corporations own our food supply from pasture to table. Heffernan is especially interested in the growing concentration and control of the food supplies by a few large transnational organizations. He cites disturbing figures: "Three firms mill 80 percent of the flour in North America. Three firms handle the distribution of three-quarters of the grain moved globally. Three firms slaughter about 82 percent of the beef cattle in North America."

Companies achieve dominance by mastering the art of "vertical integration," the attempt to control every aspect of their product, from genesis to distribution. Like the neighborhood drug pusher, these companies develop frail, chemically dependent livestock and crops, and then supply the needed fertilizers and antibiotics to sustain them.

Heffernan points to one of the three major companies that slaughter 80 percent of the cattle in Australia. "Conagra is the world's largest chemical distributor and fertilizers producer," he explains in a soft Midwest twang. "Conagra owns 12,100 barges; 2,000 railroad cars; and 100 grain elevators. They are the fourth largest [poultry] broiler producer." Heffernan sums up: "They control everything . . . all the way from seed to shelf."

It becomes obvious what is most priceless in the quest to rule the world's food supply, say advocates of biodiversity. As science and technology move ever faster than the guidelines that may harness them, the race is on to patent the very stuff of creation itself, germ plasms of the grains and plants and livestock embryos.

"Plant life arose in about 12 centers around the planet," explains Teitel. "All 12 of those are in the Third World."

While we have all of the money, he adds, the Third World has the germ plasm. This has led to an intense struggle for control of that basis for life, he says, with mostly corporations fighting to patent germ plasm from these countries. "They caught on 20 years ago--whoever controls the food supply controls everything," observes Teitel drily.

His fears are echoed by Jeremy Rifkin, author and biotechnology watchdog, who notes in Teitel's book Rain Forest in Your Kitchen (Island Press, 1992), "With the big chemical companies moving in to collect seeds and patent animal embryos, they potentially will have power over many of the living things [and] of the future of this planet."

The solution for the survival of both flora and fauna--and, ultimately, those that depend on them--is diversity, both of the gene pools and of those that try to claim ownership of them.

Teitel's remote demonstration farm is only one example of what are known as preservation breeders, a network of hobbyists and small farmers throughout the world in organizations such as the American Livestock Breeds Conservancy and Rare Breeds Survival Trust, dedicated to keeping breeds of domestic livestock from disappearing. Besides the Navajo-Churro sheep (fewer than 5,000 left in the world) and San Clemente goats (fewer than 2,000 remaining), Teitel also raises Delaware chickens and Ossabaw Island pigs, both on the American Livestock Breeds Conservancy's list of critically endangered species.

Like Teitel's organization, the farm at the Institute for Agricultural Biodiversity, an adjunct of Iowa's Luther College, attempts to both preserve breeds and educate the public about biodiversity. Its director, Peter Jorgenson, calls the institute, housed in a 19th-century barn outside of Decorah, "the first museum/zoo to entirely focus on interpreting the genetic revolution."

The solution to the shrinking diversity in our crops and livestock--and those that attempt to control them, believes Jorgensen--will be found when we start confronting and challenging some of our basic concepts about food, farming, and the economy. "In my view," states Jorgensen, "I don't call what we have in this country a farm policy or agricultural policy--we have a 'cheap food' policy."

He continues, "It doesn't factor in the social or environmental costs. It only looks at how to keep cheap food in the supermarket."

Some nations, however, are finally rebelling against this Wal-Mart approach to keeping our freezers and cupboards full, and which in the process is driving family-owned farms into extinction. Heffernan points to Sweden, which took steps to ban giant livestock containment facilities, such as one in Oklahoma that houses 1 million hogs.

"The [Swedish] government has helped the farmers during the transition," Heffernan notes. "[Now] farmers are making good money off their hogs. [They] produce some of the best pork in Europe, and family farms are being preserved."

Teitel hopes that shoppers begin to question just what their mass-produced, buck-a-quart milk or 59-cent-a-pound broiler is actually costing them--or the next generation. They can vote for change with that most democratic of ballots, he says, the almighty buck. "Shopping is where we can have a direct impact by making choices," Teitel observes. Vote for organic greens, he suggests, or brown eggs instead of white, or meat and produce from family-owned farms.

With what we buy and from whom we buy, believes Teitel, "we can make a direct choice on our future and our children's future."

This page was designed and created by the Boulevards team.

Janet Orsi

From the January 23-19, 1997 issue of the Sonoma County Independent

Copyright © 1997 Metrosa, Inc.

![[MetroActive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)