![[MetroActive Features]](/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | Sonoma County Independent | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

The Grim Sweepers

Michael Amsler

On the beat with crime-scene cleanup--a blood-soaked turf

By David Templeton

Have you eaten?" asks John Birrer of the Windsor-based Asepsis crime-scene cleanup company, cracking open a binder filled with photographs, "because these are plenty graphic." True to his word, the photos--which Birrer keeps to demonstrate the extent of the damage for insurance and other billing claims made by the property owner--tell one tale after another, some tragic, others macabre. Among the former is a teen suicide, in which a boy shot himself with his father's deer rifle--a two-year-old tragedy that still causes Birrer, an ex-cop, to tear up when describing it.

"I'm not immune to this stuff," he says, shrugging and gazing at the photo. "I experience the whole grief cycle with a lot of these jobs. I feel the sad part, the anger part, the denial part. I get upset afterwards, sometimes, sure.

"I'm human."

He turns back to the gruesome chronicle. A few pages later, he relates the case of a Santa Rosa man who died of a heart attack in his car, parked in his closed garage. His remains weren't discovered for almost three months. Fortunately, Birrer says, the car was an Oldsmobile. "None of the fluids leaked through the floorboards," he appreciatively notes, "though it was all swimming with maggots. Don't get me started talking about maggots. I know more about the life cycle of the black blowfly than anyone should."

What is clear from the photos is how extensive the damage often is in such cases.

"It's not uncommon, especially in gun-related deaths," Birrer explains, "to find blood on the ceiling, on the walls, on the floor--literally all over the place.

"People have no idea how much area can be contaminated after a single gun blast to the head."

What is clear from the photos is how extensive the damage often is in such cases.

"It's not uncommon, especially in gun-related deaths," Birrer explains, "to find blood on the ceiling, on the walls, on the floor--literally all over the place.

"People have no idea how much area can be contaminated after a single gun blast to the head."

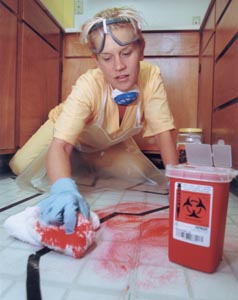

Biohazard: Kim Nootenboom dons a filtered face mask that protects crime-scene cleanup workers from contaminated blood.

BLOOD--THE RED ooze of life. It's what Homer once called the "humour as distills from blessed gods," that hard-working liquid--a warm broth of plasma and blood cells--chiefly responsible for carrying oxygen and nutrients and waste materials and carbon dioxide, back and forth, through miles and miles of veins and arteries. Blood. The average adult human being has around six quarts of the stuff pumping through him--roughly a gallon and a half.

That's not much, if you think about it, though it's plenty enough to do the job when our blood stays cozily contained beneath our easily punctured skins. Should some random accident or act of violence occur, however--should those six little quarts end up sprayed across a living room, a kitchen, a car, a sidewalk--well, the average witness would be startled to learn how much blood we really do carry around all bottled up within us.

Put another way, it's amazing how big a mess we humans can make.

As Macbeth remarked, right after murdering poor old Duncan, "Who would have thought the old man to have had so much blood in him?" Who indeed? Aside from your average surgeon, mortician, police officer, or emergency-room attendant--who certainly see their fair share of blood--there are few people alive who know as much about our life-giving fluids as those hardy, strong-stomached professionals known as "trauma-scene practitioners."

Their business: crime-scene cleanup.

Since 1993--when a former East Coast paramedic opened the nation's first cleaning service dedicated solely to the aftermath of bloody events and crimes--this startling vocation has attracted thousands of entrepreneurial mavericks: bold, unconventional people who recognize a lucrative new industry when they see it.

Practitioners can earn between $100 and $350 dollars per hour. Though work tends to be sporadic, it is sad but certain that there will always be more job opportunities. In California alone, the Department of Health Services has registered over 50 crime-scene cleanup companies. Two of those--Not-a-Trace and Asepsis Technology--are based in Sonoma County. Typical of any developing industry, the trauma-scene field is experiencing some growing pains, with ever-changing regulatory issues and the usual squabbles among competitors, each jockeying for leadership position or marketing advantage.

Homer may have been right or wrong with his poetic description of blood being the essence of the gods, but one thing every crime-scene practitioner knows for sure: cleaning the stuff up is big business.

And very hard work.

Teamwork: Trainee Gail Stryker, left, a home-health worker, with Not-a-Trace co-owners Gregg Smith, center, and trauma-scene marketer David Goforth.

IT'S UNFORTUNATE when family or friends have to clean up the mess after a loved one has died violently," says Birrer. "The act of getting in there and cleaning up a family member can only add trauma to an already traumatic experience. It's tough even for us, when we don't know the victim--and then there are all the legal parts of it that most people don't know. Individuals who have not been properly trained should not be doing this."

A former L.A. cop and Sonoma County coroner's investigator, Birrer has run Asepsis--the first operation of its kind in the area--ever since injuring his back on duty. "I was moving a corpse in the county morgue," he jauntily explains. "I ended up herniating three disks, causing a multilevel fusion. There's a metal plate in there now. Next thing I knew, I wasn't a cop anymore, and I sat there thinking, 'What the hell am I going to do now?"

As an officer, Birrer was intimately acquainted with the impacts of crime, both on the physical surroundings and on the psyches of the victim's family. Also, he'd been present on numerous occasions when, after the coroner had removed the body and police had concluded their investigation, the stunned survivors would stand outside the victim's home, frozen with uncertainty and remorse, unsure what to do next.

"It's not the responsibility of law enforcement to clean up at a death scene, unfortunately," he affirms. "But I saw plenty of people--these people are already more overwhelmed than they'd ever been in their lives--with no idea what to do next. So there was a definite need for experienced professionals to step in."

Step in he did. Since then, Birrer--along with a seasoned crew of workers, most of them former nurses, morticians, coroners, or licensed embalmers--has overseen the cleanup of hundreds of grisly events.

Only 20 years ago, blood was still just blood, and the notion of a specialized industry focusing on the cleaning of trauma scenes was unthinkable. Though certainly no less tragic and heart-rending than today, yesterday's trauma scenes--from murders to suicides to accidental and natural deaths--were at least able to be cleaned up with few worries as to the safety of the task.

(Does anyone remember 1973's Last Tango in Paris, with that unforgettable scene of the old woman, kneeling in a puddle of blood, scrubbing the remains of her daughter's suicide from the bathroom walls and shower curtains? It was an unsettling sight, to be sure. These days, with the omnipresence of such infectious agents as HIV, hepatitis B and C, and other blood-borne pathogens, such a thing would be considered a biohazard. Over the last two decades, our view of blood itself has been irreversibly altered. It is no longer merely the juice of life; blood--other people's blood, anyway--is sometimes viewed as a lethal substance, a potential poison.

Hospitals have long been required to observe heightened precautions in their handling and disposal of blood and other bodily fluids and human of tissue. Outside of the health-care industry, such waste material was routinely washed down storm drains or tossed into dumpsters and taken to the landfill. As of a year ago, however, a new state law changed all of that. The Trauma Scene Waste Management Act, authored by Sen. Ken Maddy of Fresno, set up a minimal regulatory system for the new crime-scene cleanup companies, and made it a illegal for trauma waste to be freely dumped in public places.

Under the law, practitioners must register with the DHS and must submit proof of a relationship with a licensed, medical waste treatment facility, where the troublesome blood and guts are sterilized and incinerated.

Though the AIDS virus can live outside the body only for a few seconds, after which contact with the blood is relatively safe, the deadly hepatitis B virus can live within spilled blood for up to two weeks. Therefore crime-scene practitioners are required to receive a three-part hep B vaccine. All other safety precautions, including rubber gloves, full-body suits, and sometimes even breathing apparatus, are taken seriously.

"At least, that's how it should be done," warns David Goforth of Sacramento's Hygentek Emergency Services. "No two ways about it, there are a lot of flakes out there.

"There are building owners who will clean a crime scene on their own, rip up blood-soaked carpets--and then throw it all in the trash can. There are janitorial services who might be called in to clean up after someone has died. They don't know they're breaking the law when they dispose of the waste improperly; they don't necessarily know they're putting themselves at risk of disease. I hate to say it, but there are even people within the industry who are breaking the rules--either because they don't care or because they haven't been properly trained.

"This is the sort of thing we want to stop."

In addition to cleaning up crime scenes and running Hygentek--which has recently merged with Penngrove-based Not-a-Trace Services--Goforth owns the only crime-scene cleanup supply store in the country, opened last October in Sacramento. He is also the director of the Certified Alliance of Trauma Practitioners and Emergency Responders, and in addition runs Code Red Training, which operates three classrooms, called "trauma centers," in Sacramento, Hayward, and Penngrove. Here, those interested in becoming registered trauma practitioners, as well as people already employed as cleaners, can soak up some of Goforth's considerable knowledge.

At the trauma centers--with each room staged to resemble the scene of a crime--the employees of cleaning companies, and others interested in cleaning crime scenes for a living, receive instruction and are put through "hands-on" drills. To properly set the stage, there are bright-red splatters of paint on the ceiling, the overhead fan, or the wall above a bed, behind which trainees may discover fake severed ears or fingers. Lumpy gray smears on the wall represent the ruptured brain matter after a shot to the head. Bloody polka-dots adorn the kitchen floor by the chalked-in outline of a fallen body.

It is in these training sessions--during which Goforth shares his alternately philosophical and practical approach to crime-scene conduct--that trainees get their first glimmer of what might lie ahead in the real world.

"Our job, overall, is to make it safe and habitable to utilize the building again after a traumatic event," Goforth lectures. "We are there to give dignity back to the family, because it's dignity that has been lost. The family will be feeling exposed, and probably even embarrassed, because death has brought a stream of strangers into the house, strangers who come in to look at their most private, private business."

GOFORTH has developed specific rules for working a crime scene, including tips on how to interact with family members, how to handle overlooked evidence should it be discovered along the way, and how to protect the emotional well-being of every trauma-scene practitioner. Blood is referred to on-site as "protein." Severed limbs or body parts are simply "pathology." Maggots are "vectors."

Before work begins in the impacted area, Goforth has a team member remove any photos of the victim, so the persons with their hands in the protein can avoid dwelling on the life that's been lost. To further distance the workers from the enormity of the tragedy at hand, he recommends that right-handed technicians scrub with their left hands.

"When you are cleaning up a blood pool, you use physical things like that to put yourself away from the incident," he explains. "Think of it as a metaphor. By using your left hand you acknowledge that we are in a different environment, that this is not normal. So suddenly you become less anxious, because you are constantly reminded that this is not normal. Walking into a house and finding a dead body is not normal.

"You never want that to seem normal."

Defending his cautious approach, Goforth cites statistics that show heightened rates of suicide among police officers, nurses, and firefighters, related to post-traumatic stress syndrome from close contact with violent events. Asked if he and his crew are under similar risk, he replies, "I don't want to find out. That's why I've developed this system of distancing ourselves."

Furthermore, he'd like to see his on-scene protocols become the industry standard, a benchmark that others would strive to attain. Earlier this month he submitted a list of suggestions to the DHS, which is considering ways to establish firmer standards of conduct among trauma-scene practitioners. Additionally, he'd like to see stronger enforcement of the existing dumping and safety rules, so that violators will be forced to either comply or find a new career.

"The bottom line," he says, "is that we want enlightened competitors. We don't really want to put anyone out of business. We just want competitors who are following the rules, those that understand the risks for their employees and the environment."

Goforth's partner in crime is Greg Smith [on his request, we are withholding his real last name because of the teasing his children have received in the past regarding their father's occupation]. The founder of Not-a-Trace, Smith has seen some amazing things himself. He was recently called to a storage locker where a 16-foot-long boa constrictor, locked in by its owner, had long since perished. "Talk about vectors," he says.

Smith was also the man on the scene last year in Fairfield, when--in a much publicized case--a woman was found to have been "caring" for her dead mother for over a year.

"It was like Norman Bates without the knife," Smith affirms. "The daughter was a schoolteacher, and every day she'd say goodbye to Mommy and leave the body lying in bed. She had bowls underneath to collect the fluid. That one got me. It was the weirdest thing I've ever seen."

It takes a specific kind of person to handle such surprises, he adds.

"This is more than a cleaning job. This is stressful," he observes. "You have to be tough and be able to detach from the facts of what the heck you're kneeling in, but you have to be sensitive at the same time. You don't want to screw up and say something stupid.

Such as? "I heard of a guy who finished a job, a suicide," he recalls, "and as he was leaving he turned to the family and said, 'Have a nice day.' I'd say that was pretty stupid."

Smith, Goforth, and Birrer are all optimistic about the future of the industry, ironic in that success depends on an arguably pessimistic belief that murder and suicide will not be going into decline anytime soon.

"It's a fact of life," Goforth states. "People die, and sometimes they die in bad ways. That doesn't thrill me. But we have to acknowledge the fact of mortality when we're faced with it. And in the end, isn't it still better for a trained professional to go in and do this job than to leave it to people who are just beginning to grieve?"

Smith agrees, saying, "I'll tell you this. I've worked a lot of jobs in my life, and this is the only one I've ever seen where people will come up to me and say, 'I can't tell you how much I appreciate this. I don't know what you charge, but whatever it is--it's not enough.' "

[ Sonoma County | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

It's a dirty job: Kim Nootenboom, a local child-care worker, sponges red dye at the Not-a-Trace crime-scene cleanup training facility in Penngrove.

It's a dirty job: Kim Nootenboom, a local child-care worker, sponges red dye at the Not-a-Trace crime-scene cleanup training facility in Penngrove.

Michael Amsler

Michael Amsler

From the January 21-27, 1999 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.