![[Metroactive Features]](/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | North Bay | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

Eyes on the Sky: SSU physics professor Dr. Lynn Cominsky and the new Pepperwood observatory.

Black Hole Beacons

Local physicist Dr. Lynn Cominsky charts the big bangs that lead to black holes

By Chip McAuley

Western creation myths vary in what they tell us about how the universe and the world began. The most familiar, perhaps, is that the heavens and earth were created in less than a week (with a day off for good behavior). Some tell us that our universe emerged out of nothingness or chaos, a really big egg or, perhaps, a dream. Modern science, however, says the universe began 13.7 billion years ago with the big bang, a cosmic orgasm of sorts that created the entire universe--a universe that continues to expand.

Whichever myth may be true, it is irrefutable that out there in the cosmos, the banging hasn't stopped. Now Sonoma State University physicist Dr. Lynn Cominsky, chair of the physics and astronomy department, and her cadre of NASA-funded star trekkers are about to mourn the demise of the very first stars created in the universe. Flaming out in spectacular super-supernovae, or hypernovae, called gamma ray bursts (GRBs)--the biggest explosions in the universe since the big bang--these celestial events create one of the most mysterious and compelling phenomena in creation: black holes.

Gamma ray bursts last between only two and 30 seconds and are thought to occur when stars 100 times the size of our sun die. The closest observed GRB was around 1 billion light years away; the farthest, 12 billion. With the universe now aged to a 13.7 billion-year perfection, scientists plan to use the $250 million Swift Observatory--launched in Houston this Nov. 22 and named for having the speed necessary to capture data on such short-lived explosions--to discover, among other things, the fate of the very first stars. It is a voyage not only to the edges of the known universe, but to a time more distant than the human mind can comprehend.

Through the NASA-funded Education and Public Outreach (E/PO) program run by Cominsky at SSU, her team of local scientists provides vital information on the project to other scientists, the media and the public. They now have the opportunity to discover a black hole or two themselves at the California Academy of Sciences' newly built robotic observatory at the Pepperwood National Preserve in Santa Rosa.

The NASA E/PO building on the SSU campus is nestled in a virtually secret locale. There, Cominsky and her team plot the course for outreach for the next generation of NASA projects, make mission proposals and do active research. There's a real Contact vibe to the room--an observer half expects Jodie Foster to rush in at any minute and make some startling revelation. The similarities are, in fact, uncanny.

"Except we're not sending someone through an interdimensional portal to the other side of the universe," says education program manager Sarah Silva.

At least, not until more NASA funding arrives.

"This is the realization of a life's dream," says student Sean Greenwalt, "I wanted to do science since before I could articulate."

"It's a lot of fun to help design educational materials linked with missions," says fellow student Logan Hill. "I think it's really cool--I'm working for NASA."

A Life in the Stars

Being a space case is nothing new for Cominsky, who in 1970 was involved with the Uhuru project, the very first X-ray satellite ever launched. She grew up reading science fiction authors such as Isaac Asimov, Harlan Ellison, Robert A. Heinlein and Philip K. Dick, and--of course--loving Star Trek. In fact, a model she made of the Starship Enterprise NCC-1701-D hangs above her desk in the E/PO office.

Such inspirational sci-fi authors and series have been responsible for launching more than one scientist's career and remain an example of how the science fiction of yesterday becomes the science of today through the work of scientists like Cominsky. Indeed, she came to an exciting realization early on in her scientific career--one that astounded even her.

"Someone's going to pay me to do science fiction for a living," she remembers marveling when she became a physicist. Since then she's discovered pulsars and X-ray bursts, written 50 published scientific papers in peer-reviewed journals and taught thousands of physics students. In addition to currently heading the E/PO program, she serves as deputy press secretary for the American Astronomical Society.

While it may be initially puzzling to figure out what the connection is between Sonoma County and NASA, the answer is surprisingly simple: Cominsky. Having been a professor at SSU for 19 years (spending the first 15 years in research mode), Cominsky has pushed her program forward from a smallish $50,000 annual budget to the current $1.3 million needed to accomplish its mission.

Even Harvard University, she says, has asked her team do its space outreach. The group's biggest project is the Gamma Ray Large Area Space Telescope, due for launch in 2007 in collaboration with Stanford University. Cominsky's most recently completed outreach project supported the launch of the Swift Observatory mission in a collaboration between NASA and the British and Italian space agencies.

"The launch was filmed by Thomas Lucas Productions for use in a PBS Nova show slated to air in 2006 and tentatively titled "Black Holes: The Other Side of Infinity," Cominsky says. "Part of the PBS special is a planetarium show being developed in partnership with the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. Both will feature the Swift launch as well as detailed simulations that allow the viewer to feel as though they are taking a trip into a black hole."

Far-reaching in their efforts, Cominsky's E/PO team look forward to a future when they can participate in even more missions exploring cosmic conundrums. And of course, there's also the more mundane.

"I give a lecture called 'Things My Mother Never Told Me about the Universe,'" Cominsky chuckles, explaining that her interest was piqued when her mother took her girl scout troop out stargazing one night. Such humble beginnings, however, led her eventually to Brandeis University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for a Ph.D.

Between universities and following her time on the Uhuru project, Cominsky worked at Harvard on what was then one of the most powerful computers in the world, the IBM 360--a computer that used punch cards and was less powerful than any single desktop computer currently in her office.

While that computer monolith seems laughable now, it nonetheless proved to be the great scientific leap that would one day allow Cominsky's colleague Tim Graves to construct the entire Pepperwood robotic observatory from scratch.

What's it like building a space observatory from the ground up?

"Cold in the morning. Hot in the afternoon. And wet when it rains," says the jocular Graves. "It was a lot of fun. I feel kind of sad now that it's complete," he says of the observatory, which is named GORT after the robot in the film The Day the Earth Stood Still.

"GORT will also monitor jets of light streaming out of supermassive black holes billions of times as massive as our sun.," Cominsky explains. "These monsters are the prime targets for observations."

According to Graves, GORT can "think for itself," noting that once the robotic telescope receives notification of a celestial event, the dome opens automatically, the camera is turned on and scientists receive e-mail notification.

Furthermore, Graves says, "The program is accessible to any person in the world who has an Internet connection," as the Global Telescope Network site is online at http://gtn.sonoma.edu.

Hypernovas Near Home?

The two leading theories of the hypernova debate, according to Cominsky, say that either these tremendous explosions come from the deaths of very big stars or result from the decaying orbits of neutron stars finally colliding in a colossal explosion just reaching Earth now after billions of years.

What if scientists are wrong? What if a GRB happened for an altogether different reason--and close to our dear planet Earth?

"It would vaporize the entire planet instantly," chimes in Dr. Phil Plait, author of Bad Astronomy and a member of Cominsky's team.

Not to worry.

"All the leading theories propose that GRBs are beacons for black holes," says Cominsky. This means they must come as the result of the death of massive stars far larger than Sol. "And we don't see any massive stars in our local stellar neighborhood that could produce GRBs in the near future," she assures.

But what could GRBs mean for other possible planets and civilizations far older than Earth and our solar system? The question is compelling.

"There is evidence that one GRB was responsible for the Ordovician mass extinction about 440 million years ago," says Cominsky. "It was the second-largest extinction in the earth's history, the killing of two-thirds of all species, and could be the result of a GRB within 10,000 light years of Earth."

First Stars, First Civilizations

With the discovery in the 1990s of the first planets outside our solar system, humanity's timeless quest to find extraterrestrial life seemed one step closer to achievement. The SETI, or Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence, project continues, as do conspiracy theories that aliens have already visited the planet and experimented on humans with anal probes and the like. Some theories even posit that ancient aliens once ruled the planet or helped create the human race.

Would 1.7 billion years be enough time for life to develop and flourish on a planet at some distant end of the galaxy, only to have Cominsky and her team witness its destruction 12 billion years later?

The first generation of stars, she says, were likely formed during the first few hundred thousand years of the universe. They lack heavy metal elements, with only hydrogen and helium existing at that point in time. Any planets formed during this period would likely not be the same as Earth. As Cominsky explains, there was no carbon, nitrogen or oxygen at this point in cosmic history. She and others hope to eventually get a glimpse back into these early days of the universe. "No one," she says almost wistfully, "has ever seen the first generation of stars." It is one of her team's greatest hopes.

The second generation of stars offer all new possibilities to consider. "The supernova deaths create the elements needed for life," she explains, adding that "there's nothing to rule out" the chance that some of the stars she could be studying in the future may have had planets with intelligent life on them. Just because it took 5 billion years for our solar system to form, she says, doesn't mean others could not have formed far earlier.

Though a theoretical calculation called the Drake equation estimates how many intelligent civilizations could exist in the universe, the question of how many civilizations and planets might accompany each hypernova explosion remains a mystery--at least for now.

Birth of the Gamma: Active galactic nuclei such as this one depicted in an artist's illustration, are the nursery of gamma rays, jets of matter and energy that stream outward from the depths of black holes.

Black Holes in a Black Sky

"Now that Swift is orbiting the earth, there are many opportunities for students and the general public to get involved in the chase to discover the newly born black holes that are created by GRBs," Cominsky says.

At the Pepperwood robotic observatory, her group of scientists, aided by physics students, will reap the rewards of their outreach efforts. "If it's dark outside and the bursts are in the right part of the sky, our telescope can get the positional information directly within a few seconds, and the robotic telescopes can point there right away. Then we can take the data, and project scientists are notified via e-mail, pager and telephone, and the information can then be analyzed somewhat later."

If a hypernova happens at the right place and time, no one in the know should be surprised if Cominsky's team of Einsteins in the making announces a series of startling new discoveries about the fate of GRBs and the black holes they create. Supported by NASA, it seems likely that significant figures in the next generation of cosmic exploration could come right here from Sonoma County. According to Cominsky, however, most people are shocked when they learn that NASA has placement at SSU. And though she feels blissfully overwhelmed most of the time, the future of the program, she assures, will be one of expansion--just like the universe itself.

"We've made a difference at the local, regional and national levels," she says. "This program gives us a chance to connect to local high school students and research for college students."

Dark Energy

Ultimately, what can be learned from the study of these big bangs--these GRBs--and the black holes that form in their wake? What about all this talk of the beginning of the universe, extraordinary explosions, black holes and looking back into the seemingly timeless universal past? Doesn't it only lead to questions about how it will all end? Will everything just continue expanding until the universe burns itself out? Will the cosmos fall back in on itself in what some scientists call the "big crunch," or will it surprise us with something totally different and as yet unimaginable?

Will space research finally allow us to explore the universe through interdimensional portals or unlock the secrets of time travel in order to witness the universe of ancient (or future) days? Sometimes it seems as if nothing is out of reach when mind and money combine in the right hands--and in a brilliant scientific and poetic spirit.

For now, perhaps the physicist will have to give way to the poet. After all this, Robert Frost may have known best in his poem "Fire and Ice," when he wrote, "Some say the world will end in fire, / Some say in ice. / From what I've tasted of desire / I hold with those who favor fire. / But if it were to perish twice, / I think I know enough of hate / To say that for destruction ice / Is also great / And would suffice."

Cominsky agrees with Frost--at least about the ice.

"As to the end of the universe," she says, "Most believe that dark energy is causing the expansion of the universe to accelerate, and therefore we will end in ice, as everything gets farther apart and colder forever. But don't worry, it won't be for billions and billions of years."

Perhaps poetry and physics are ultimately the same thing, and one day Cominsky's students, or students of her students, may unlock the cosmic mystery that explains it all.

[ North Bay | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

Photograph by Rory McNamara

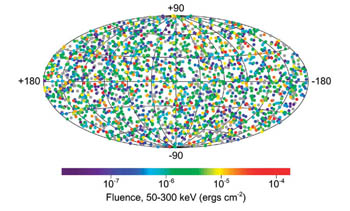

Sky Map: Somewhere in the universe each day, a black hole is born, its arrival heralded by the 'scream' of a gamma ray burst. This map depicts a day in the life of the universe.

Photograph by Aurore Simmonet

Hypernova: Hypernovae are possibly the biggest explosions in our universe since the big bang.

For more information on the E/PO program, visit http://epo.sonoma.edu. As part of the California Academy of Sciences Dean Lecture Series, Dr. Lynn Cominsky gives a presentation titled 'Exploding Stars, Blazing Galaxies and Monstrous Black Holes: The Extreme Universe of Gamma-Ray Astronomy' on Monday, Jan. 24, at Kanbar Hall in the San Francisco Jewish Community Center. 3200 California St., San Francisco. 7:30pm. $4. 415.321.8000.

From the January 12-18, 2005 issue of the North Bay Bohemian.