The Light in the Attic guys were in town last week, and no, that’s not a Shel Silverstein fan club; rather, it’s a Seattle-based record label responsible for reissuing lost classics, both well-known (the Louvin Brothers’ Satan Is Real) and obscure (the Lialeh soundtrack, anyone?).

Currently, Light in the Attic is enjoying tremendous success with the albums of Rodriguez, a Detroit musician many have rediscovered through the documentary film Searching for Sugar Man, in theaters now. Much of the film takes place in South Africa, where, amid 1970s apartheid, Rodriguez was as famous as the Rolling Stones—and where, in the days before the internet made fact-checking such rumors simpler, he was said to have committed suicide onstage.

Here in America, Rodriguez was a flop. (His record company executive estimates his total U.S. sales at “six.”) I won’t ruin the documentary, other than to say that, although Rodriguez’s rediscovery is a familiar story, and the minutiae of the hunt threatens its momentum, the film’s payoff is one of the most joyous things to be seen in a movie theater this year.

Rodriguez himself must be joyous, too. Forty years after his albums Cold Fact and Coming from Reality tanked, Light in the Attic has been able to write Rodriguez his first-ever royalty checks. “He’s easily our biggest seller right now,” said Light in the Attic’s Josh Wright, sipping a beer at the Last Record Store in Santa Rosa while the clerks bought even more copies from the back of his van.

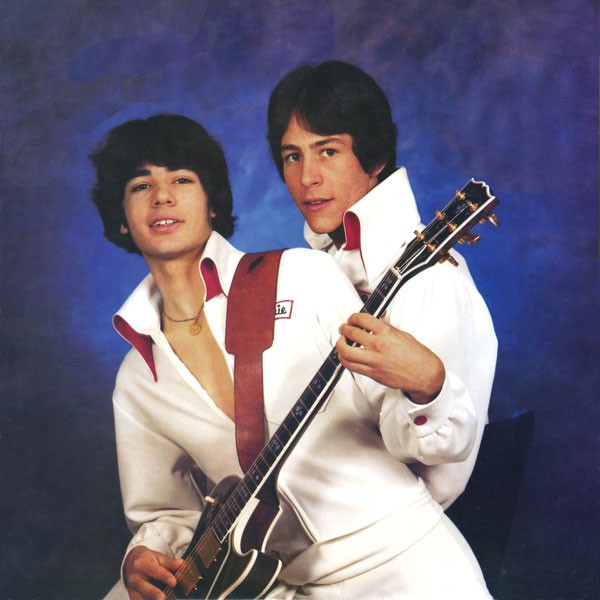

Matt Sullivan, label founder, was poring through the vinyl bins. “This is my favorite album of the year,” he said, holding a copy of Dreamin’ Wild by Donnie and Joe Emerson. And then the story came: two isolated teenagers growing up on the family farm in rural Washington showed enough musical promise that their dad—”the greatest dad in the world,” said Sullivan—took out a loan to buy his sons new equipment and to build a top-notch recording studio on the property. The year was 1979.

The resulting record sold very, very poorly. To pay off the loan, the Emersons’ dad literally lost the farm, selling 1,500 acres of land.

Here’s the big question—and it’s applicable to any feel-good story of musical rediscovery—is the music any good? I bought a cassette of Dreamin’ Wild off Sullivan, and it’s the best five bucks I’ve spent all month. The brothers’ only exposure to music was a tinny AM radio in the family tractor, and their own songs reflect this rural innocence.

“Baby,” in particular, is filled with wide-eyed mystique, a two-chord masterpiece that, thanks to Light in the Attic, has been covered by Ariel Pink and used for a key scene in Celeste and Jesse Forever. While Rodriguez’s music channels Bob Dylan, Cat Stevens and other familiar stars of the era, Dreamin’ Wild seems to exist in its own universe—a slice of purity in a pre-fab world.