Danger Zone

Michael Amsler

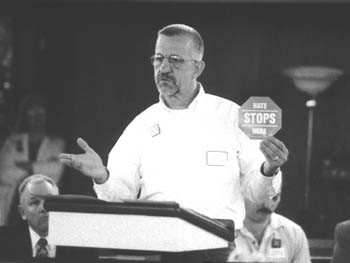

Hate stops here: District Attorney Mike Mullins, left, looks on as Allen Odom, a member of the Sonoma County Human Rights Commission, displays a new sign intended to help raise awareness about local hate crimes.

Hate crimes forum draws mixed review

By Paula Harris

WE NEED TO DO something,” says Lorene Irizary, director of the Sonoma County Commission on Human Rights, talking about a rash of recent local reports of bigotry. “We want people to feel part of a solution and not powerless.”

Irizary joined several dozen community members and law enforcement officials last week at a forum at the Guerneville Community Church to develop an effective way to deal with hate crimes in the county. Among others in attendance were Sonoma County Sheriff Jim Picinnini, Sonoma County District Attorney Mike Mullins, and 5th District Supervisor Mike Reilly.

The forum was well timed, but underscored the complex nature of hate crimes in the county–several people protested that sheriff’s deputies themselves were guilty of hate crimes against local gays.

Still, following recent reports of a man allegedly stalking and raping four members of Sonoma County’s lesbian community–an assailant who has reportedly vowed “to get them all”–and an incident last week in which Ku Klux Klan hate literature was placed inside copies of a local newspaper and distributed to homes in five neighborhoods, the call for a renewed look at hate crimes in Sonoma County was well received overall.

Irizary has known about the frequently underreported problem in this community for a while. Two years ago, the Sonoma County Commission on Human Rights held countywide hearings on the issue. Both commissioners and participants, including city council members, representatives from the American Civil Liberties Union, and members of local law enforcement agencies were struck by the magnitude of local hate-related incidents, aimed primarily at the gay and lesbian communities in the Russian River area. “People were surprised at what was happening in our own community,” recalls Irizary. “We don’t always see it or hear it. When we start hearing testimonies of individual incidents, we realize the problem is bigger than we thought and it’s happening right here.”

The commission then began an ongoing effort to halt crimes that are motivated by real or perceived issues of race, ethnicity, national origin, religion, age, disability, gender, or sexual preference. Together with the District Attorney’s Office and the Sonoma County Sheriff’s Department, the commission established the Sonoma County Hate Crime Prevention Network to combat hate violence.

As part of that effort, a weeklong education program for west county residents this week was timed to correspond with the start of the tourist season in May. “During the tourist season, there are more hate crimes in the Russian River area,” explains Irizary. “We wanted to have training for business owners and employees, specifically at gay resorts on the Russian River that become targets or have incidents so they can learn how to help de-escalate hate, how to respond, and what type of information to capture for law enforcement.”

THE REV. JIM Spahr, president of the North Bay chapter of Parents, Families, and Friends of Lesbians and Gays says harassment in schools is still going on. “In Petaluma, there has been a gay-related youth suicide every year since 1995,” he says. PFLAG claims that there were 2,529 reported episodes of anti-gay harassment and violence in 14 U.S. cities in 1996, a 6 percent increase over 1995. Overall, anti-gay violence rose 102 percent from 1990 to 1995.

According to Picinnini, in 1996 there were 13 hate crimes reported in unincorporated areas of Sonoma County; in 1997, seven; and two so far this year. “But I don’t believe these numbers,” says Picinnini. “A lot of these crimes go unreported, and we need to have community involvement to have the courage to report these.”

Reilly agrees. “Some people are reluctant to come forward to law enforcement to report they have been victimized,” he says. “We want to actively track behavior. We want to create a safe environment for people to come to the table.”

However, several individuals spoke candidly of their outright distrust of law enforcement officials. “I’ve walked the planet a long time as a gay man and have been a target for hate… . The police protect me but are also my persecutors,” said one man, who asked Picinnini: “What are you doing to educate your men on the police force? What about their value systems and what do they believe about me?”

Picinnini replied: “A majority of our men and women in uniform treat people equally. We tell [deputies], ‘Whatever beliefs you have, you are to put them aside when you put the uniform on.’ “

The man shot back: “I will hold you accountable. I will be in your face about accountability.”

Another gay man claimed to have been beaten up by sheriff’s deputies in his home. “I know inside my soul and heart that I was the victim of a hate crime. Unfortunately, the hate crime was from the sheriffs,” he said.

And yet another man claimed that when he tried to report a hate crime after a neighbor allegedly had ordered his rottweiler to “kill the faggot,” the deputy had refused to mark the correct box on the report designating the incident as a hate crime.

“I don’t think you understand what a hate crime is,” he complained to the sheriff. “It’s going to take a lot of effort on your part.”

“I would not feel safe in the custody of the Sheriff’s Department,” agreed Pastor John Torres of the Metropolitan Community Church of the Redwood Empire, who is so concerned about the problem of bigotry that he has formed an Interfaith Response to Hate Crimes to effect a united response to verbal abuse and violence directed at gay men and lesbians in Sonoma County. “A lot of what’s happening is happening in the Sheriff’s Department. What specific ways are you raising consciousness?” he asked Picinnini.

Picinnini responded that his department is undergoing cultural-diversity training. He has also appointed a liaison between the gay community and his department.

“What we need to do is be very intolerant of the first symptoms [of bigotry],” says Mullins. While hate crimes are a specific section of the penal code, he adds, they are hard to classify. According to Mullins, it’s often difficult to determine whether to prosecute an incident as a hate crime, particularly when free speech muddies the issue. “We cherish our First Amendment so much, we allow it to be abused,” he says.

From the April 30-May 6, 1998 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.

© Metro Publishing Inc.